Francesca Portante d’Alessandro

Rome, Italy

Blood has always been depicted in art, from cavemen’s hunts, to medieval altarpieces and battle scenes, to modern film and photography. Blood is able to simultaneously represent both life and death, the sacred and profane, violence and martyrdom, disease and healing, purity and impurity.1 Its meaning, however, can also vary depending on whose blood it is and who is looking.

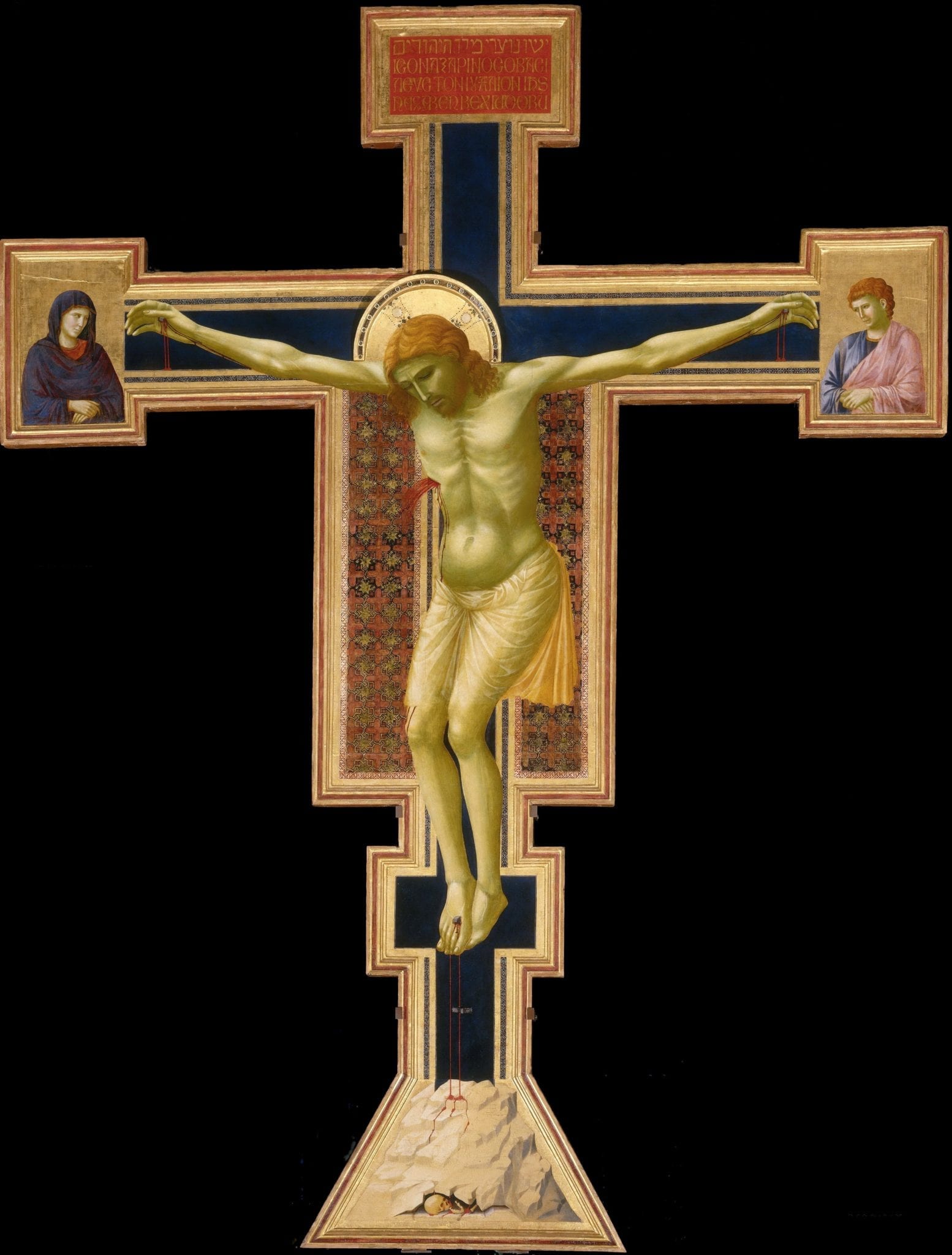

Blood, running through the veins of the living, is connected with animation and life, a link established by early medicine and explored by philosophers and physicians. Second century physician Galen identifies it as one of the four bodily fluids ruling human temperament, responsible for delivering spiritus vitalus to the body. The oxymoron of blood alluding to life in art is that in order to do so it has to be visible through wounds; hence also alluding to the threat and imminence of death. Rose George identifies the “two-faced nature of blood,” which she explores through the metaphor of the Gorgon Medusa.2 Her serpentine coiffure was believed to carry both lethal (right side) and life-giving (left side) blood. Such dichotomy can be explored in art through the representation of Christ on the cross in late medieval works, where artists used vivid depictions of blood flowing to both accentuate the death of Christ’s body, and allude to the promise of eternal life.3 In Giotto’s Santa Maria Novella crucifix (Fig 1), the animating power of blood is emphasized and contrasts with the rigid, heavy body. The animation is physical, as the rivulets are the most dynamic element in the painting: a large gush flows out of the side wound and drips downward while the blood from the hands falls vertically upon the border of the cross. Two different shades of red are used to spatially differentiate between the wound, the blood projection in the air, and that on the body. However the artist also deviates from a realistic depiction as the fluid seems to defy gravity by only streaming downward rather than back into the picture plane.4 Thin lines of blood seep into the rock of Golgotha below, foreshadowing the promise of eternal life.5

Blood’s dual nature, while widely present in religious iconography, has also been exploited in socio-politically charged contemporary works such as Andres Serrano’s 1990 Blood and Semen V, representing the two mixed fluids as if under a microscope. Like blood, semen carries both productive and destructive power, which was especially felt at the height of the AIDS crisis. While these fluids are essential for conception and birth, their mixing was also responsible for the spread of HIV. The photograph hence awakens anxieties about disease and infection, while also alluding to the cycle of life and death. Blood can grant life through processes such as transfusion, but it can also destroy the body if infected. In the work it is simultaneously pure and impure. Serrano’s work further demonstrates that the meaning of blood in art is dependent on whose blood it is. While Christ’s blood represents salvation in medieval paintings, in Serrano’s work the viewer does not know whose blood it is, which adds an element of fear from the possibility of disease.

Another significant meaning of is that of identity and belonging. This aspect is discussed by David Stone in his study of Caravaggio’s blood signatures. In The Beheading of Saint John the Baptist, (Fig 2) painted for the Catholic military order of the Knights of Malta, Caravaggio signs his name in the blood spurting from John the Baptist’s neck wound. Caravaggio arrived in Malta in 1607 after having fled Rome and Naples following the death of Ranuccio Tommasoni. While the blood signature has traditionally been understood as an act of contrition for his crime, Stone puts forward the idea that this was rather a declaration of his new role and status in Malta as part of the crusading order for whom the work was created.6 Caravaggio was in fact made a brother in the Knights Hospitaller of St. John of Jerusalem on July 14, 1608, only a few months before the work was created. By writing his own name in St. John’s blood, Caravaggio is directly linking himself to the saint, almost creating a visual bloodline. This is particularly relevant because as the only non-noble member of the order, the artist would have felt pressure to prove his worth and lineage. The signature is not only a celebration of his new social standing but also proof of nobility deriving from faith and devoted service, which originates directly from the saint himself.

A relevant comparison can be made with a series of portraits by Ravi Chander Gupta depicting Indian martyrs in blood. By using his own blood to paint the martyrs, Gupta is creating a sacrificial portrait: he is sacrificing his own blood to remember and pay homage to national heroes.7 Like Caravaggio he is creating a connection in blood, however the blood stands for a shared national heritage rather than an individual’s lineage. Caravaggio used paint to create his signature in blood; Gupta instead used real blood to create his portraits.

These works operate within a value system defined by Foucault as the “society of blood” in which “power spoke through blood” and stands for sacrifice, strength, and heroism.8 This only relates to the blood of male heroes, however; female blood, especially menstrual blood, is often seen as monstrous and infected. The depiction of menstrual blood in art can highlight a woman’s identity, acting on some level like Caravaggio’s signature. Yet working within a context of subversion, Ingrid Berthone-Moine’s 2009 photographic series Red is the Colour consists of twelve photographs of women using their menstrual blood as lipstick. The work subverts and questions cultural stereotypes, such as menstruation being regarded as abject waste separate from reproduction, and that of menstruating women as “monsters” who should not have intercourse.9 The photos portray menstruation through the metaphor of the painted mouth, alluding to a bleeding vulva or even a vagina dentata. In addition, since wearing menstrual blood on the lips implies tasting it, it also plays into the fear of lesbian vampirism, where the female vampire is portrayed not only as a sexual deviant, but also raises the threat of castration in male viewers by crossing gender boundaries.10 For a female viewer, however, the photographs may instead signify identity, as menstruation is a decisive moment in the transition from girl to woman.

Blood in art can carry many meanings. Returning to Rose George’s statement, blood is more than “two-faced”; it is multifaceted with endless nuances and variations.

References

- Dawn Perlmutter, ‘The Sacrificial Aesthetic: Blood Rituals from Art to Murder’, Anthropoetics, V no. 2 (2000), p.1

- Rose George, Nine Pints: A Journey Through the Money, Medicine, and Mysteries of Blood, (2018), pp.4-6

- Beate Fricke, ‘A liquid history: Blood and animation in late medieval art’, RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics, No. 63/64, (2013), p.54

- Fricke p.62

- Fricke p.63

- David M. Stone, ‘Signature Killer: Caravaggio and the Poetics of Blood’, The Art Bulletin, Vol. 94, No. 4 (2012) p.574

- Jacob Copeman, ‘The art of bleeding: memory, martyrdom, and portraits in blood’, Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, (2013) pp.153-154

- Michel Foucault, History of Sexuality 1: The Will to Knowledge (Penguin: 2008) p.147

- Ruth Green-Cole, ‘Visualising the Menstrous: Infectious Blood in Contemporary Art, Monsters and the Monstrous, (2014) p.66

- Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, (1980) p.293

FRANCESCA PORTANTE D’ALESSANDRO was born in Brazil and studied humanities in Italy. She has a degree in History of Art from University College London and is interested in the intersection of art and popular culture.

Submitted for the 2019–2020 Blood Writing Contest

Leave a Reply