Joanne Jacobson

New York, New York, United States

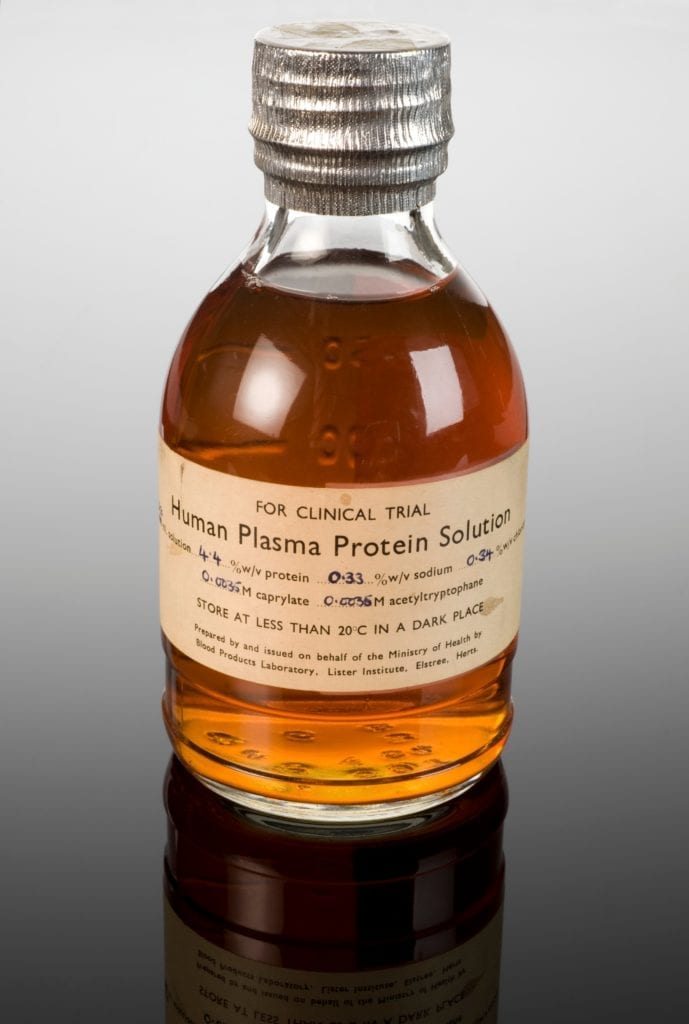

Human plasma protein solution in bottle, Hertfordshire, Engl. Science Museum, London. CC BY 4.0.

None of us live to adulthood without seeing our own blood—growing up, I witnessed my blood flow free of my body too many times to count. The bleeding knee picked clean of leaves and gravel after my father sent me spinning down the driveway on my birthday bike; the splinter’s wake of red, thin enough to be erased with a single swipe of my hand. The embarrassing mark of puberty on school clothes. The fall that sent me in seek of help, bearing into the back seat of a taxi the unseemly memory of myself spilled onto cement, my chin gashed and bloody. Accidents just like the accidents that befall most human beings making their clumsy, not always attention-paying, way through the world, trailing the memory of blood—freshly moist, then scabbed in the air and light; the body’s fragile spots opened and then quietly closed.

But the year I turned sixty, blood’s invisible pathways to my brain became mysteriously blocked, shaking my world, sending out muddled danger signals: a saw-toothed rainbow that drifted over my vision with greater and greater frequency; words that stuck to one another in my mouth. In the emergency room I learned that blood can slowly transform the self in secret, and make a person different in a second. Suddenly I was a patient with a frightening diagnosis, a rare clotting disorder that only a hospital would enable me to survive.

Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura affects just a handful of people in a million. The treatment of choice is plasmapheresis, a procedure in which the patient’s entire blood supply is siphoned off and centrifuged so that the plasma containing rogue antibodies and damaged enzyme can be replaced with healthy donor plasma, and fresh platelets can grow in their stead. I have lived now to see my blood intentionally emptied out. Tethered by the jugular to a big machine, I have witnessed one set of tubes fill with my lifeblood, while another, mixed with clear donor plasma, sends blood circling back. And even as blood has been reiterated to me as a physical thing, a fluid like any other washing in and out of my body, it has been revealed in the slowly passing hours of plasma exchange as a force—as deep as my beating heart.

Blood has long been endowed with mysterious power, subject in virtually every culture to regulation. In the biblical temple where holy men in white came alone into God’s presence, the magic of expiating guilt and of reaching the divine with thanks depended on draining entirely of blood the sheep and the goats whose corpses were placed upon the sacrificial altar. Holding a living pigeon or turtledove, its wings beating between the palms of his hands, the priest would pinch off the bird’s head and rip open the body by the wings, letting its blood empty over the altar before offering the bird to the fire.

In its prohibition against eating or drinking blood, Leviticus set for members of a precarious desert tribe the most radical of boundaries: the threat of abandonment to the wilderness. Anyone who partakes of it shall be cut off. Many centuries later, the same warning continued to mark off community. My great-grandfather was a ritual butcher in turn-of-the-twentieth-century Michigan, tasked with slaughtering kosher meat for the tiny group of Jews who had settled there after fleeing Eastern Europe. To him fell the responsibility of administering death in the bloodless way of tradition, so that Jews could eat what he killed.

The seventeenth-century physicians who first experimented with blood transfusion permitted themselves to carve into the living flesh of dogs and horses and deer to observe their working hearts, the red and the blue of circulation. Still, when scientists began transfusing animals, they recognized blood as a medium charged with essential spirit. They selected for transfusion animals whose dispositions they saw as desirable and hoped to pass on to humans: lambs and calves, for example, for their gentleness.

What animal, I wonder, would I allow access to my own veins, to give its life for me, to be stitched to me; to be my intimate, a bleeding ally? Alien as those brute scenes of sacrifice and surgery may now feel, they speak for human beings’ recognition that blood is a fundamental aspect of what we share with other living things. And we remain who we were then, as much body as we were in the world that gathered in robes around desert wells for the water upon which human life depended; animal among the species saved by Noah two by two.

Blood has taken me to the boundary between life and death, between modern science and ancient spirituality. The heavy tubing taped to my head was slowly unwound every day in the hospital, and I was left lashed to the lumbering machine—watching what used to be invisible to me, observing what used to be whole disassembled before my wondering eyes.

How could I not be changed by this, by the sight of my own blood?

Have I already been transformed by the plasma from human donors that is mixed like syrup into my own blood, saving me but invisibly changing me—if not to a lamb or a calf or a dog then perhaps to someone who will die young from an inherited disease?

In the hospital I waited in bed for results from dawn blood draws, so unobtrusive that they barely interrupted my sleep: for my “numbers,” my daily platelet count. A bit of blood always seeped into the clear plastic tubing splayed across the back of my hand; the quickly accessible beachhead established at every patient’s hospital admission in case of an emergency. And yet what got counted each day remained invisible. I hoped for information that would mark my progress toward recovery—my movement back into the self that used to be me. But that self, the self that hardly gave thought to my blood, has retreated forever, transformed and transfixed by blood’s ongoing drama.

Blood is in so many ways ordinary; the tactile, visible stuff of human life. It was transported during the London Blitz in modified milk bottles packed into milk crates, delivered to the bleeding wounded throughout the wrecked city by converted ice cream vans. And yet in the very qualities that make the blood that is pumped through our bodies as mundane as daily life, we recognize what makes violently spilled blood so shocking, and such a familiar metaphor for loss of life.

To this day, the blood lost by communal martyrs remains a sacred responsibility of the Jewish community. Its remnants are scraped by volunteers from the ground and buried with the dead; returned to the earth with what is left of their bodies clad in the clothes they were wearing when they were murdered. No martyr, I searched for days for my blood at the spot in front of my apartment building where I had tripped on an untied shoelace and fallen. On my knees I looked for a rust-colored stain on the soiled city sidewalk, wondered if a neighborhood dog might have lapped up my spilled blood as I left for the ER with a paper towel pressed to my chin—hoped stubbornly for a lingering public sign of my vulnerable, surviving self.

OANNE JACOBSON, PhD, taught for thirty years in the Department of English at Yeshiva University in New York City, and served as Associate Dean for Academic Affairs at Yeshiva College. She holds a B.A. from the University of Illinois, Urbana, and an M.A. and Ph.D. from the University of Iowa, all in American Civilization. Jacobson’s monograph Authority and Alliance in the Letters of Henry Adams was published in 1992; her memoir, Hunger Artist: A Suburban Childhood came out in 2007. Her essay volume on chronic illness, Every Last Breath, is forthcoming in 2020.

Submitted for the 2019–2020 Blood Writing Contest & Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 12, Issue 2 – Spring 2020

Leave a Reply