Peter H. Berczeller

Edited by Paul Berczeller

An excerpt from Dr. Peter Berczeller’s memoir, The Little White Coat.

Ward 64, the only female medical ward at Cook County Hospital, was to be the home base for daily meetings of our group of five with the instructor assigned to us. Our space—immediately next door to the patients’ toilet—was the size of a coat closet. It boasted a rickety table for our coats and precious doctors’ bags, plus six metal chairs. There was no window, nor was there ventilation; a weak, ancient lighting fixture high up on the cracked ceiling illuminated the scene. There was so little room on the ward that our hole-in-the-wall was forced to fulfill an additional function at night. On most mornings, we’d walk in and bump into a bed taking up most of the room still containing its occupant, waiting patiently for her one-way trip to the morgue.

Dr. Wolf—prematurely grey, early 30’s—was to be our oracle for the next two months. There was a dishevelled look about him, the Chicago Sun-Times always sticking out of his right suit pocket. He had just finished his residency and was waiting to take the specialty boards in internal medicine; “otherwise I wouldn’t be doing this shit job,” he assured us at our first session. The gruff attitude turned out to be just a put-on, but from the very beginning, it seemed to me that he was a fountain of knowledge, that he knew everything. At that point, we knew next to nothing—and he really was smart—but even if he hadn’t been, there was no way we could have detected it. Almost preemptively, just to set the tone that learning medicine is arduous, even painful, he began the first session by cutting us—actually me—down to size. I was giving some inane clinical opinion which he dismissed with a memorable putdown. “You,” he said, pointing at me (he hadn’t put names and faces together yet). “Your mother may think you know medicine, but I know different!” I kept the expression in mind, and I used it with generations of my own students for a long time after.

Every time a patient was assigned to me, I went through an exhaustive investigation, beginning with the history, physical examination, and analysis of the laboratory results, before going on to a review of the articles in the medical literature which applied to her case. The whole oeuvre would take up at least twenty pages of dense handwritten prose. Our teacher must have understood the advantages of peer pressure in teaching clinical medicine, because one of us was scheduled to read his case out loud each morning.

There are certain smells that stick around, that can be evoked in an instant like a pungent memory. At Cook County Hospital it was the smell of old clothes, dirty feet peeping through cracked shoes, and excreta—vomit, urine, and stool. The totality of the stench was mixed in with—but not neutralized by—a potent, nose-tickling disinfectant, possibly some super Lysol. After a while, I could have recognized the various buildings in the Cook County complex blindfolded; the smell of the obstetrics building different from that of the pediatrics building, which in turn was not the same odor emanating from the area where the patients with infectious diseases were kept. Still, the scent of the pathology building was unique; the formalin floating in the lobby came out to greet the nose halfway across the courtyard that led to the entrance.

During the first week on Ward 64, I saw a case of leprosy for the first time. Also, three ladies who were friends came in with acute kidney failure. They had all attended the same party, where an excessive amount of Spanish Fly (a supposed aphrodisiac) was on the menu. These diagnoses were just icing on the cake, the ones stored deep in memory; utilized maybe once in a professional life, or, more likely, never. Common things happen commonly, as Dr. Wolf used to say, so the twenty-page discussions the others on my team and I had to write dealt with more everyday illnesses like pneumonia, kidney infections, or strokes. At least that was what the ward staff thought was wrong with their patients, until they were presented at the daily sessions in the pathology building in what were officially called Clinicopathologic Conferences.

Clinicopathologic Conferences at Cook County Hospital

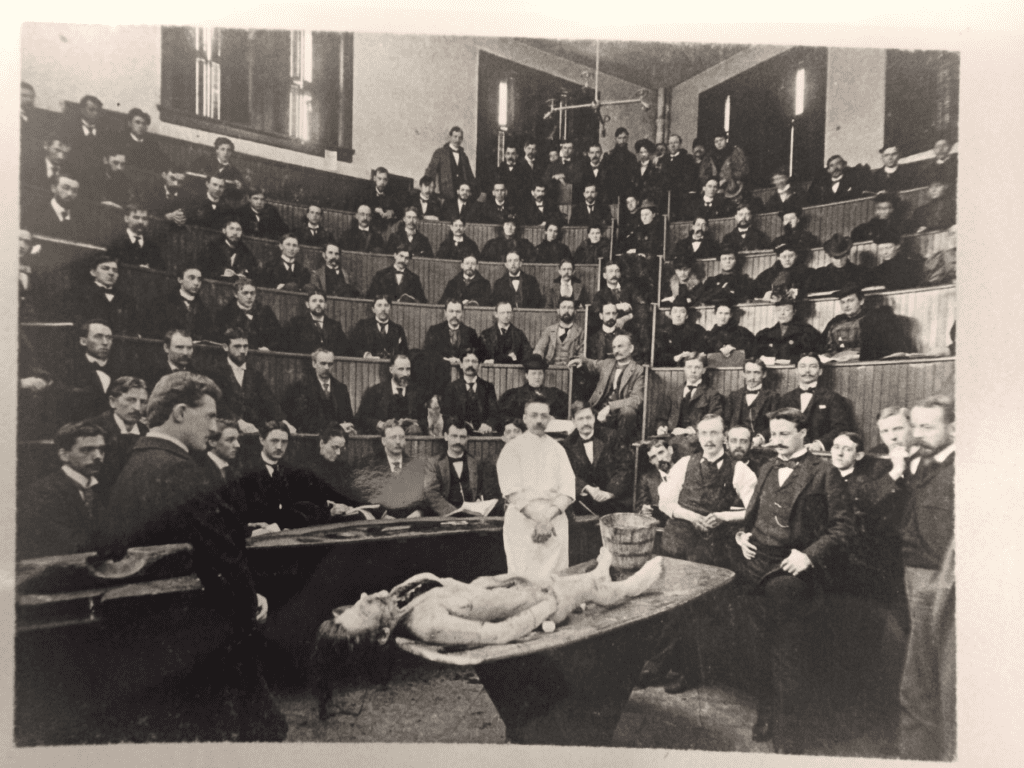

Late every afternoon, house staff and students gathered in one of the smaller amphitheatres—normally used for autopsies—for the grand ritual of the CPCs, as they were known. On the big lab table facing the audience, some twelve pans covered with towels were arrayed, containing the organs of most of the patients who had died in the hospital over the previous 24 hours. Pathology trainees in long smocks and round caps—the getups reminiscent of priests of some exotic religion—stood watch over the pans, while their counterparts, the surgical and medical residents, sat in the first couple of rows fidgeting over the voluminous charts in their laps.

There was good reason for the house staff to be nervous. There is always some wiggle room when the “impression” part of the chart is filled in, which suggests what you think may be wrong with the patient. This preliminary thinking has a reasonable look to it while the patient is struggling to survive. Yet by the time the autopsy is finished it can prove to be embarrassingly inaccurate. At those daily conferences in the pathology amphitheater, Dr. Szanto, the second-in-command of the department—an amiable-looking Hungarian with a thick accent—always had the last word, like the quizmaster on a TV show.

Thursday mornings we would all troop over to what I have always thought of as the All-Star CPC. The larger amphitheater was packed with the great and the good of the medical center, with a sprinkling of lowly students. A printed history of the case was distributed at the door, and a buzz of anticipation—reminiscent of an opera house before the performance—permeated the room. Dr. Popper, the chief of pathology—he had an Austrian accent like Erich von Stroheim—stood there like a welcoming host. His benign appearance was just a mask; to those in the know, the source of his smile was the ambush he was preparing for the day’s speaker. The rules of the game were simple: the pathology resident presented the clinical information about the patient, then it was up to Popper’s potential victim to predict what the autopsy would show. There was much exciting give-and-take between the two; the clinician would invariably complain he did not have enough information to come up with a diagnosis, and Popper kept insisting he had put out enough clues to “zink a pattleship.” Isidore Snapper—a famous clinician in his day—was a frequent visiting sage, and on one occasion groused even more than usual about the meager facts he had been given to work with. Hans Popper, thick fleshy lips, ears sticking way out, rejected the appeal. Snapper was Dutch, but for some reason he spoke with a vaguely French accent. “Docteur Poppeur,” he replied, “there iz an old Fransh proverb: Even ze most biootiful woman in ze world can only give what she has!” I still do not know if he was referring to himself or to his tormentor.

The jousting between Popper and his visitors was the best kind of theater because it engaged not only the minds but also the visceral responses of the audience. Watching one skilled diagnostician after another putting out a moment-to-moment bulletin of what he was thinking and why he was thinking it was mesmerizing for a neophyte like me. It stimulated me to at least try to keep up with the reasoning; and it was not difficult to tell whose side the audience was on in this struggle: most everyone was rooting for the clinician to come up with the right answer. As the climax approached, the tension in the large hall became more and more palpable. A few years later, working my own way through another maze of contradictory symptoms and confusing lab results for the benefit of a new generation of students, I began to understand how those speakers I had so looked up to must have wanted to win, and so did I.

PETER H. BERCZELLER, MD, was born in Vienna, Austria in 1931. He attended The Chicago Medical School and received his MD there in 1956. He was a practicing internist from 1960 to 1992, at which time retired from private practice. He was also on the Attending Staff at New York University Medical Center and Clinical Professor of Medicine at New York University School of Medicine for many years. In addition to multiple contributions to the medical literature, he is the author of several books dealing with medicine and one novel. His 1994 book, Doctors and Patients: What We Feel About You was released by Simon and Schuster. He lived in the Dordogne, in France.

PAUL BERCZELLER, son of Dr. Peter Berczeller, edited and reviewed this piece.

Leave a Reply