Mariel Tishma

Chicago, Illinois, United States

The road for African Americans in the medical professions has not been easy. Enslaved Africans received no education.1 During the first half of the nineteenth-century medical schools in the North would admit only a very small number of black students. Even after the Civil War, African Americans continued to be refused admission to colleges, medical associations, and hospitals.2

But those driven to heal refused to give up. When no American schools enrolled them, they studied abroad3 or started their own schools4 and training hospitals. Howard University was established in 1868, and Meharry Medical School opened in Nashville in 1876, both historically black medical schools. Several other schools were founded but later closed under the reforms recommended by Fletcher Report.5

Medical associations also refused to admit African Americans, who in response created their own associations like the National Medical Association thus overcoming limitations on their careers.6

And as the number of African Americans in medicine began to increase, several achieved prominence for their achievements as well as serving as role models for the generations that came after them.

|

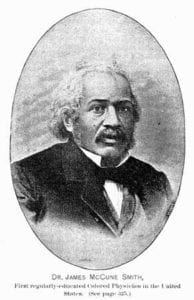

| Portrait of James McCune Smith. by Unknown Artist. From Recollections of Seventy Years by Daniel Alexander Payne published in 1888. Public domain. |

James McCune Smith

Dr. James McCune Smith was the first African American to earn a medical degree and practice in the United States.7 Born in 1813, Smith was the son of a self-emancipated slave.8 He began his studies at the New York African Free School.9 He was an excellent student, and was selected at age eleven to give a speech for the Marquis de Lafayette during a visit.10 Upon graduation, he was apprenticed at a blacksmith shop, but continued his education privately, learning Greek and Latin.

Smith then applied to medical colleges throughout New York, but was turned away because of his race.11 Black abolition and religious leaders in New York funded his education, and he traveled to Scotland to study at the University of Glasgow. There he received his medical degree in 1837.12

Smith studied the classics, languages, statistics, and philosophy. He was fluent in Greek, Latin, and French and proficient in four other languages. His medical education concluded with clinical work in Paris following a year-long infirmary clerkship. On returning from Scotland he opened a private practice and pharmacy in New York.13

McCune Smith devoted much of his life to writing. He published the first case report by a black physician in America in the New York Journal of Medicine.14 In 1846 he published a pamphlet on the effect of climate on health.15 Many of his works used medicine and statistics to combat untruths about race, and he addressed the errors and biases of the US census of 1840.16

By the time of the Civil War, McCune’s productivity declined, as did his health. In 1863 he was no longer able to see patients, and he died two years later.

|

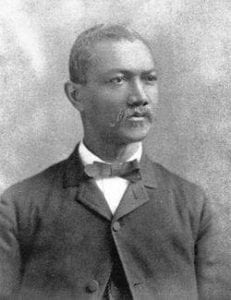

| Alexander Thomas Augusta by Unknown, before 1891. Public domain. |

Alexander Thomas Augusta

Dr. Alexander Thomas Augusta was born free in Virginia in 1825. As young man he first made his way to Baltimore, Maryland, where he worked as a barber. Denied admission to the University of Pennsylvania because of his race, he studied medicine in Toronto at Trinity Medical College.17 He practiced in Toronto, treating both black and white patients. In 1863, following the outbreak of the American Civil War, Augusta wrote to Abraham Lincoln to request permission to serve as a surgeon for the US army. The Army Medical Board at first rejected his request, stating he was unsuitable both because of his race and because of his Canadian citizenship. Augusta wrote again, appealing the rejection and was finally allowed to take the qualifying exam. He passed, and at the age of thirty-eight he was commissioned as surgeon for the Union Army.

Dr. Augusta was appointed to the 7th United States Colored Infantry, and the white surgeons in the unit refused to work with him. He was reassigned, and then served in a rotating capacity until the war’s end.18 He was the highest ranking black officer in the Union Army.19 By 1868 Dr. Augusta had moved to Washington D.C. and had applied for a faculty position at the newly established Howard University20 where he became the first African American professor of medicine. He retired from Howard University in 187721 and continued to practice medicine until his death, and he was buried at Arlington National Cemetery.22

|

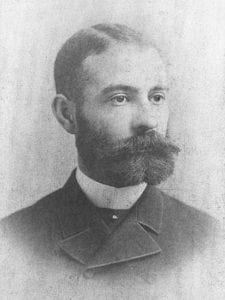

| Daniel Hale Williams by Unknown, c. 1900. Public domain. |

Daniel Hale Williams

Dr. Daniel Hale Williams was born in Pennsylvania23 and moved with his family to Baltimore, where he first became a shoemaker’s apprentice, then a barber in Janesville, Wisconsin.24 He then worked as an apprentice with Dr. Henry Palmer and graduated from Chicago Medical School in 1883.25 He began practice in Chicago, where he was one of only four black physicians in the city.26 In 1889 he was named to the Illinois State Board of Health, improving public sanitation to control scarlet fever, typhoid, diphtheria, and yellow fever.27 The following year Williams was approached by Reverend Louis Reynolds, whose sister had been denied admittance to nursing schools because of her race. Williams and Reynolds worked to open a teaching hospital for African American physicians and nurses—the Provident Hospital and Nursing Training school.28

In 1893 Dr. Williams performed one of the first open heart operations on a man who came to Provident with stab wounds. Dr. Williams opened the chest, rinsed the wound, and repaired a tear in the pericardium.29 The patient survived surgery then returned for a second surgery to drain the wound, and he lived for years afterwards.30 While this was not the first surgery on the heart,31 at that time any cardiac surgery was considered impossible and indecent. Dr. Williams forged ahead with the procedure anyway, saving his patient’s life.

In 1894 Williams became chief surgeon at Freedman’s Hospital in Washington D.C. where he instituted strict antisepsis policies,32 reorganized the surgery department, and established both a nursing and surgical training program.33 In 1895, Dr. Williams co-founded the National Medical Association to aid black physicians and surgeons who had been turned away from the American Medical Association.34 He remained chief of surgery at Freedman’s until 1898, when he returned to Chicago35 working at Provident Hospital, St. Luke’s, and Cook County Hospitals.36 There, he wrote reports on ovarian cysts in African American women, disproving myths that black women did not develop these cysts.37

When the American College of Surgeons was founded in 1913, Dr. Williams was one of its first members.38 He would remain the only black fellow until 1934.

|

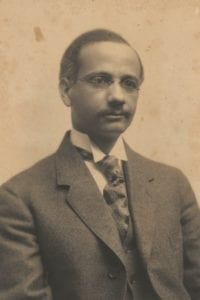

| Solomon Carter Fuller, c. 1910. New York Public Library. Public domain. |

Solomon Carter Fuller

Born in Liberia in 1872, Dr. Solomon Carter Fuller migrated to the US in 1889 to study medicine. Four years later, he had earned his AB from Livingstone College, and in 1897 was awarded his MD from Boston University.

In 1904 Fuller was invited along with four other doctors to study under Dr. Alois Alzheimer.39 There he performed autopsies40 and prepared and examined samples.41 This intimate view of the brain helped him discover the plaques indicative of Alzheimer’s disease.42

In 1912 Dr. Fuller published a report of the ninth confirmed case of Alzheimer’s disease in the Journal of Nervous and Mental Diseases.43 As part of this paper, Fuller translated Alzheimer’s original case into English for the first time.44 Because of his careful translation, more researchers could read and expand on Alzheimer’s work.

In 1919 Dr. Fuller became a faculty member at Boston University. This made him one of the first African American physicians working as faculty at a college other than Meharry or Howard.45 He was instrumental in training psychiatrists to treat veterans at the Tuskegee VA hospital.46

Dr. Fuller was an early member of the American Psychiatric Association.47 He retired from Boston University in 1937, but continued to practice privately until 1953 when he died from complications of diabetes. 48

|

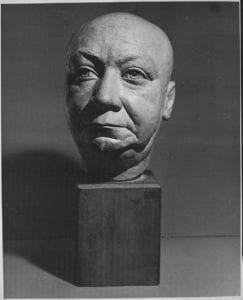

| Head of Dr. Louis Wright by William E. Artis. U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, Institution National Archives at College Park. Public domain. |

Louis T. Wright

Dr. Louis T. Wright was born in La Grange, Georgia. His father, a doctor, died while he was still young, and his mother married another physician, Dr. William Fletcher Penn.49

Wright enrolled at Clark University, his stepfather’s school, and graduated valedictorian in 1912.50 He then applied to Harvard Medical School. The interviewer challenged Wright’s eligibility, but after taking an exam, he was allowed to enroll.51 This was not the end of his challenges. Among them, he was told he could not complete his obstetrics rotation at the same hospital as the rest of his class as “Black students did not attend to White women.”52 Louis stated that he was third in line to name his rotation, and so would complete it with his class. He did so.

After graduation, his applications to major Boston hospitals were rejected, so he took a position at Freedman’s (Howard) Hospital.53 Here he researched the use of the Schick diphtheria test on darker skin, publishing his results and disproving those who said the test would not be effective.

In 1919 Wright joined the staff of Harlem Hospital. During his thirty-three year long career there he established a surgical residency program and a nursing school. In 1934 he was elected to the American College of Surgeons, only the second African American fellow since its founding.

He became Chief of Surgery at Harlem in 1938. In 1940 Wright was forced to slow down, suffering from severe pulmonary tuberculosis. He underwent three years of treatment and hospitalization. In 1943, returning to Harlem, he was once again selected as chief of surgery. 54

In 1948 he led the first team to use the antibiotic aureomycin in humans. That year he also founded the Harlem Hospital Cancer Research Foundation, research he would pursue until the end of his career.55

|

| Myra Adele Logan, center doctor. Louis T. Wright and colleagues at patient bedside, Harlem Hospital, New York, N.Y from Louis Tompkins Wright papers, 1879, 1898, 1909-1997. H MS c56. Harvard Medical Library, Francis A. Countway Library of Medicine, Boston, Mass. CC BY-SA 3.0. |

Myra Adele Logan

Dr. Myra Adele Logan was born in 1908 in Tuskegee, Alabama. She came from a medical family; her brother was Dr. Arthur R. Logan, after whom the Arthur R. Logan Memorial Hospital is named.56

She began her career with a bachelor’s degree in psychology from Columbia University. She spent a year working on staff at the YMCA in Connecticut, and then won the first Walter Gray Crump Scholarship, which allowed her to attend medical school at the New York Medical College.

Dr. Logan took her residency at Harlem Hospital, working in emergency medicine, and would stay on as a surgeon after her term.57 She was hard working, dedicated, and able,58 performing both useful research and life saving surgery. In 1943 she became the first woman to perform an open-heart surgery in what was only the ninth ever open-heart operation.59 She also worked with Dr. Louis Wright on antibiotic research.60 Dr. Logan was the first woman elected a fellow of the American College of Surgeons, serving as a role model to many.61

She would go on to pioneer diagnostic techniques for breast cancer in the 1960s62 before dying in 1977.

|

| Dorothy Lavinia Brown. Changing the Face of Medicine Collection. United States National Library of Medicine. Public domain. |

Dorothy Lavinia Brown

Dr. Dorothy Lavinia Brown was born in 1919. She spent much of her childhood in an orphanage.63 At the age of five she underwent a tonsillectomy, which reportedly sparked her interest in medicine.64 When she turned thirteen, her birth mother returned to the orphanage hoping to take her in, but the two did not get along.65 At age fifteen she ran away, attempting to enroll in Troy High School without guardians or an address. Troy’s principal arranged a foster family for her, and they became a major source of support for her medical career.66

In 1948 Brown completed her medical degree at Meharry College. She pursued a year’s internship at Harlem Hospital, but was turned down when applying for surgical residence there. She faced almost universal opposition to her pursuit of surgery, as it was believed women were not capable of performing surgery.67 In the end she completed her surgical residency at Meharry College.

From 1957 to 1983 Brown served as chief of surgery for Nashville’s Riverside Hospital and was a clinical professor of surgery at Meharry.

In 1956 Dr. Brown became the first single woman to be an adoptive parent in the state of Tennessee. She would also become the first African American woman elected to Tennessee state legislature in 1966. She served as a consultant for the National Institutes of Health in 1982, received a humanitarian award from the Carnegie Foundation in 1993, and received the Horatio Alger Award in 1994.68

Studying the lives of these pioneers is both an inspiration and a reminder. Their dedication to the art and science of healing makes them a living record of the challenges many have faced in their pursuit of medicine, and role models for those who face challenges of their own today.

End Notes

- Writing Group on the History of African Americans and the Medical Profession. “African American Physicians & Organized Medicine: Acknowledging our Painful Legacy.” Slides presented at the National Medical Association, Sponsored by the American Medical Association. https://www.ama-assn.org/about/ama-history/history-african-americans-and-organized-medicine.

- Axel C. Hansen, “African Americans in Medicine,” Journal of the National Medical Association volume 94, no. 4 (April, 2002): accessed November 2019, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2594211/pdf/jnma00321-0108.pdf.

- Ibid, 267.

- Karen Jordan, “The Struggle and Triumph of America’s First Black Doctors,” The Atlantic December 9, 2016, https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2016/12/black-doctors/510017/.

- “Black History Month: A Medical Perspective.” Duke University Medical Center library & Archives. Last Updated March 1, 2019. Accessed November 2019. https://guides.mclibrary.duke.edu/blackhistorymonth.

- Writing Group on the History of African American. “African American Physicians.”

- “African American Medical Pioneers,” American Experience produced by WGBH Educational Foundation, accessed November 2019, http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/partners-african-american-medical-pioneers/.

- James McCune Smith (foreword by Henry Louis Gates Jr.), The Works of James McCune Smith: Black Intellectual and Abolitionist, ed. John Stauffer, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006), xix.

- “Dedication: James McCune Smith,” The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education vol. 55 (Spring 2007): accessed November 2019, https://www.jstor.org/stable/25073612.

- Thomas M. Morgan, “The education and medical practice of Dr. James McCune Smith (1813-1865), first black American to hold a medical degree,” Journal of the National Medical Association vol. 97 no. 7 (July, 2003): 605, accessed November 2019, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2594637/.

- “Dedication: James McCune Smith,” The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education.

- “African American Medical Pioneers,” American Experience.

- James McCune Smith (foreword by Henry Louis Gates Jr.), The Works of James McCune Smith, xiv-xxi.

- Thomas M. Morgan, “The education and medical practice of Dr. James McCune,” 610.

- Leslie A. Falk, “Black Abolitionist Doctors and Healers, 1810-1885,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine vol. 54. no. 2 (Summer 1980): 260, accessed November 2019, https://www.jstor.org/stable/44442951.

- Heidi L. Lujan and Stephen E. DiCarlo, “First African-American to hold a medical degree: brief history of James McCune Smith, abolitionist, educator, and physician,” Advances in Physiology Education vol. 43 issue 2 (June, 2019): 134, accessed November 2019, https://doi.org/10.1152/advan.00119.2018.

- Gerald S. Henig, “The Indomitable Dr. Augusta: The First Black Physician in the U.S. Army,” Army History , No. 87 (Spring 2013): 24-28, accessed November 2019, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/26298851.

- Gerald S. Henig, “The Indomitable Dr. Augusta: The First Black Physician in the U.S. Army,” 27.

- Jimmy Fenison, “Alexander T. Augusta (1825-1890),” Blackpast.org, March 29, 2009, Accessed November 2019. https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/augusta-alexander-t-1825-1890/.

- Gerald S. Henig, “The Indomitable Dr. Augusta,” 29.

- Jimmy Fenison, “Alexander T. Augusta (1825-1890),” Blackpast.org.

- Gerald S. Henig, “The Indomitable Dr. Augusta,” 30.

- “African American Medical Pioneers,” American Experience.

- “History- Dr. Daniel Hale Williams,” The Provident Foundation, Accessed November 2019, http://provfound.org/index.php/history/history-dr-daniel-hale-williams.

- W. Montague Cobb, “Daniel Hale Williams, 1858-1931,” Journal of the National Medical Association vol. 45 no. 5 (September 1953): 380, accessed November 2019, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2617252/?page=1.

- “History- Dr. Daniel Hale Williams,” The Provident Foundation.

- Ellen Bailey, “Daniel Hale Williams,” EBSCOhost (2007), accessed November 2019, https://gatekeeper.chipublib.org/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=f6h&AN=25181505&site=ehost-live&scope=site.

- “History- Dr. Daniel Hale Williams,” The Provident Foundation.

- “African American Medical Pioneers,” American Experience.

- Harris B Shumacker Jr, “The First Suture-Closures of Cardiac Wounds” in The Evolution of Cardiac Surgery, (Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1992), 13.

- Allen B. Weisse,“ Cardiac Surgery A Century of Progress,” Texas Heart Institute Journal vol. 38 no. 5 (2011): 486, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3231540/pdf/20111000s00005p486.pdf.

- Ellen Bailey, “Daniel Hale Williams.”

- Alisha J. Jefferson, Tamra S. McKenzie, “Daniel Hale Williams, MD:“A Moses in the profession”,”American College of Surgeons Clinical Congress Poster competition 2017, 26, accessed November 2019, https://www.facs.org/~/media/files/archives/shg%20poster/2017/04_daniel_hale_williams.ashx.

- Herbert G. Ruffin II, “Daniel Hale Williams (1856-1931),” Blackpast.org, January 17, 2007, accessed November 2019, https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/williams-daniel-hale-1856-1931/.

- “History- Dr. Daniel Hale Williams,” The Provident Foundation.

- Cobb, W. Montague, “Daniel Hale Williams, 1858-1931,” 383.

- Ellen Bailey, “Daniel Hale Williams.”

- “African American Medical Pioneers,” American Experience.

- Madison Gray, “Dr. Solomon Carter Fuller, Mind Mender,” TIME Magazine, January 12, 2007, http://content.time.com/time/specials/packages/article/0,28804,1963424_1963480_1963460,00.html.

- Camille Heung, “Solomon Carter Fuller (1872-1953),” Blackpast.org, June 29, 2008, Accessed November 2019, https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/fuller-solomon-carter-1872-1953/.

- W. Scott Terry, “A Missed Opportunity for Psychology: The Story of Solomon Carter Fuller,” Observer vol. 21 issue 6, June/July, 2008, access date, https://www.psychologicalscience.org/observer/a-missed-opportunity-for-psychology-the-story-of-solomon-carter-fuller.

- Madison Gray, “Dr. Solomon Carter Fuller, Mind Mender.”

- Lucy Ozarin, “Solomon Carter Fuller: First Black Psychiatrist,” Psychiatric News vol. 37 issue 17 (September 6, 2002), accessed November 2019, https://doi.org/10.1176/pn.37.17.0019.

- W. Scott Terry, “A Missed Opportunity for Psychology.”

- W. Montague Cobb, “Solomon Carter Fuller, 1872-1953,” Journal of the National Medical Association vol. 46 no. 5 (September 1954): 370, accessed November 2019, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2617492/?page=1.

- Jeanne Spurlock, “Early and Contemporary Pioneers” in Black Psychiatrists and American Psychiatry, ed. Jeanne Spurlock, 1st ed (Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 1999), 4.

- “Dedication: Solomon Carter Fuller,” The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education, no. 44] (Summer, 2004): 1, accessed November 2019, https://www.jstor.org/stable/4133708.

- Madison Gray, “Dr. Solomon Carter Fuller, Mind Mender.”

- “Louis Tompkins Wright, MD, FACS, 1891–1952,” American College of Surgeons Archives, accessed November 2019, https://www.facs.org/about-acs/archives/pasthighlights/wrighthighlight.

- P. Preston Reynolds “Dr Louis T. Wright and the NAACP: Pioneers in Hospital Racial Integration,” American Journal of Public Health vol. 90 no. 6 (June 2000): 884, accessed November 2019, https://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/pdfplus/10.2105/AJPH.90.6.883.

- “Louis Tompkins Wright, MD, FACS, 1891–1952,” American College of Surgeons Archives.

- P. Preston Reynolds “Dr Louis T. Wright and the NAACP:” 885.

- “Louis Tompkins Wright, MD, FACS, 1891–1952,” American College of Surgeons Archives.

- P. Preston Reynolds “Dr Louis T. Wright and the NAACP,” 886-890.

- W. Montague Cobb, “Louis Tompkins Wright, 1891-1952,” Negro History Bulletin Bulletin vol. 16 no. 8 (May, 1953): 178-179, accessed November 2019, https://www.jstor.org/stable/44214570.

- “Dr. Myra Adele Logan,” Journal of the National Medical Association vol. 69 no. 7 (1977): 527, accessed November 2019, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2536929/?page=1.

- The Biographical Dictionary of Women in Science, ed. Marilyn Bailey Ogilvie, Joy Dorothy Harvey, Volume 2, L-Z (New York: Routledge, 2000), 800.

- Peter B. Flint, “DR. MYRA LOGAN, 68,” Obituaries, The New York Times, January 15, 1977, https://www.nytimes.com/1977/01/15/archives/dr-myra-logan-68-physician-in-harlem-she-was-believed-to-be-the.html.

- “Dr. Myra Adele Logan,” Journal of the National Medical Association, 527.

- “New Potent Antibiotic,” The Science News-Letter vol. 54, no. 5 (July 31, 1948): 69, accessed November 2019, https://www.jstor.org/stable/3925723.

- “Dr. Myra Adele Logan,” Journal of the National Medical Association, 527.

- The Biographical Dictionary of Women in Science, 800.

- “Dr. Dorothy Lavinia Brown,” Changing the Face of Medicine, U.S. National Library of Medicine, Last updated June 3, 2015, accessed November 2019, https://cfmedicine.nlm.nih.gov/physicians/biography_46.html.

- Olga Bourlin, “Dorothy Lavinia Brown (1919-2004),” Blackpast.org, January 19, 2015, accessed November 2019 https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/brown-dorothy-lavinia-1919-2004/.

- Wini Warren, “Dorothy Lavinia Brown From Orphan to Surgeon to Teacher” in Black Women Scientists in the United States, (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2002), 19.

- “Dr. Dorothy Lavinia Brown,” Changing the Face of Medicine.

- Wini Warren, “Dorothy Lavinia Brown From Orphan to Surgeon to Teacher” 20.

- “Dr. Dorothy Lavinia Brown,” Changing the Face of Medicine.

References

- “African American Medical Pioneers.” American Experience produced by WGBH Educational Foundation. Accessed November 2019. http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/partners-african-american-medical-pioneers/.

- Bailey, Ellen. “Daniel Hale Williams.” EBSCOhost (2007) https://gatekeeper.chipublib.org/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=f6h&AN=25181505&site=ehost-live&scope=site.

- The Biographical Dictionary of Women in Science. Edited by Marilyn Bailey Ogilvie, Joy Dorothy Harvey. Volume 2, L-Z. New York: Routledge, 2000.

- “Black History Month: A Medical Perspective.” Duke University Medical Center library & Archives. Last Updated March 1, 2019. Accessed November 2019. https://guides.mclibrary.duke.edu/blackhistorymonth.

- Bourlin, Olga. “Dorothy Lavinia Brown (1919-2004).” Blackpast.org. January 19, 2015. Accessed November 2019. https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/brown-dorothy-lavinia-1919-2004/.

- Byrd, W. Michael, Linda A. Clayton. “Race, Medicine, and Health Care in the United States: A Historical Survey.” Journal of the National Medical Association vol. 93, no. 3 Suppl (March 2001): 11S-34S. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2593958/?page=1.

- Cobb, W. Montague. “Daniel Hale Williams—Pioneer and Innovator.” Journal of the National Medical Association vol. 36 no. 5 (September, 1944): 158-159. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2616588/?page=1.

- ________. “Daniel Hale Williams, 1858-1931.” Journal of the National Medical Association vol. 45 no. 5 (September 1953): 379-385. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2617252/?page=1.

- ________. “Louis Tompkins Wright, 1891-1952.” Negro History Bulletin vol. 16 no. 8 (May, 1953): 170, 178-180. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44214570.

- ________. “Solomon Carter Fuller, 1872-1953.” Journal of the National Medical Association vol. 46 no. 5 (September 1954): 370-372. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2617492/?page=1.

- Dailey, U. G. “Daniel Hale Williams, M.D., LL.D., F.A.C.S.” Journal of the National Medical Association vol. 23 no. 4 (1931): 173-175. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2625133/?page=1.

- “Dedication: James McCune Smith.” The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education vol. 55 (Publication Month, Year): https://www.jstor.org/stable/25073612.

- “Dedication: Solomon Carter Fuller.” The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education ,no. 44 (Summer, 2004): 1. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4133708.

- “Dr. Alexander T. Augusta: Patriot, Officer, Doctor.” U.S. National Library of Medicine. First published October 1, 2010. Accessed November 2019. https://www.nlm.nih.gov/exhibition/bindingwounds/pdfs/BioAugustaOB571.pdf.

- “Dr. Dorothy Lavinia Brown.” Changing the Face of Medicine. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Last Updated June 3, 2015. Accessed November 2019. https://cfmedicine.nlm.nih.gov/physicians/biography_46.html.

- “Dr. Myra Adele Logan.” Journal of the National Medical Association vol. 69 no. 7 (1977): 527. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2536929/?page=1.

- Falk, Leslie A. “Black Abolitionist Doctors and Healers, 1810-1885.” Bulletin of the History of Medicine vol. 54 no. 2 (Summer 1980): 258-272. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44442951.

- Fenison, Jimmy. “Alexander T. Augusta (1825-1890).” Blackpast.org. March 29, 2009. Accessed November 2019. https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/augusta-alexander-t-1825-1890/.

- Flint, Peter B. “DR. MYRA LOGAN, 68.” Obituaries. The New York Times. January 15, 1977. https://www.nytimes.com/1977/01/15/archives/dr-myra-logan-68-physician-in-harlem-she-was-believed-to-be-the.html.

- Gray, Madison. “Dr. Solomon Carter Fuller, Mind Mender.” TIME MagazineJanuary 12, 2007. http://content.time.com/time/specials/packages/article/0,28804,1963424_1963480_1963460,00.html.

- Hansen, Axel C. “African Americans in Medicine.” Journal of the National Medical Association vol. 94, no. 4 (April, 2002): 266-271. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2594211/pdf/jnma00321-0108.pdf.

- Henig, Gerald S. “The Indomitable Dr. Augusta: The First Black Physician in the U.S. Army.” Army History , No. 87 (Spring 2013): 22-31. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/26298851.

- Heung, Camille. “Solomon Carter Fuller (1872-1953).” Blackpast.org. June 29, 2008. Accessed November 2019. https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/fuller-solomon-carter-1872-1953/

- “History- Dr. Daniel Hale Williams.” The Provident Foundation. Accessed November 2019. http://provfound.org/index.php/history/history-dr-daniel-hale-williams.

- Jefferson, J. Alisha, Tamra S. McKenzie. “Daniel Hale Williams, MD:“A Moses in the profession”.” American College of Surgeons Clinical Congress Poster competition 2017. 25-33. https://www.facs.org/~/media/files/archives/shg%20poster/2017/04_daniel_hale_williams.ashx.

- Jordan, Karen. “The Struggle and Triumph of America’s First Black Doctors.” The Atlantic, December 9, 2016. https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2016/12/black-doctors/510017/.

- Larner, Andrew. “Solomon Carter Fuller (1872-1953) and the Early History of Alzheimer’s Disease.” Advances in clinical neuroscience & rehabilitation. January 31, 2013. Accessed November 2019. https://www.acnr.co.uk/2013/01/solomon-carter-fuller-1872-1953-and-the-early-history-of-alzheimers-disease/.

- “Louis Tompkins Wright, MD, FACS, 1891–1952.” American College of Surgeons Archives. Accessed November 2019. https://www.facs.org/about-acs/archives/pasthighlights/wrighthighlight.

- Lujan, Heidi L and Stephen E. DiCarlo. “First African-American to hold a medical degree: brief history of James McCune Smith, abolitionist, educator, and physician.” Advances in Physiology Education vol. 43 issue 2 (June, 2019): 134-139. https://doi.org/10.1152/advan.00119.2018.

- McCune Smith, James (foreword by Henry Louis Gates Jr.) The Works of James McCune Smith: Black Intellectual and Abolitionist. Edited by John Stauffer. New York: Oxford University Press, 2006.

- “Miracle Drug.” Ebony, vol. 4 issue 8 June 1949. 13-17. https://gatekeeper.chipublib.org/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=f6h&AN=49187146&site=ehost-live&scope=site.

- Morgan, Thomas M. “The education and medical practice of Dr. James McCune Smith (1813-1865), first black American to hold a medical degree.” Journal of the National Medical Association vol. 97 no. 7 (July, 2003): 603-614. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2594637/.

- “New Potent Antibiotic.” The Science News-Letter vol. 54, no. 5 (July 31, 1948): 69. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3925723.

- Oduro, Awura Ama. “Dr. Louis T. Wright.” Consortium on the History of African Americans in the Medical Professions. Accesed November 2019. http://chaamp.virginia.edu/node/3849.

- “Opening Doors: Contemporary African American Academic Surgeons.” U.S. National Library of Medicine. Last updated July 17, 2013. Accessed November 2019. https://www.nlm.nih.gov/exhibition/aframsurgeons/history.html.

- Ozarin, Lucy. “Solomon Carter Fuller: First Black Psychiatrist.” Psychiatric News vol. 37 issue 17 (September 6, 2002). https://doi.org/10.1176/pn.37.17.0019.

- Reynolds, Preston P. “Dr Louis T. Wright and the NAACP: Pioneers in Hospital Racial Integration.” American Journal of Public Health vol. 90 no. 6 (June 2000): 883-892. https://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/pdfplus/10.2105/AJPH.90.6.883.

- Riley, Wayne J. “The History of America’s Premier Independent Black Medical School.” The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education, no. 60 (Summer, 2008): 74-76. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40407189.

- Ruffin II, Herbert G. “Daniel Hale Williams (1856-1931).” Blackpast.org. January 17, 2007. Accessed November 2019. https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/williams-daniel-hale-1856-1931/.

- Shumacker Jr, Harris B. “The First Suture-Closures of Cardiac Wounds” in The Evolution of Cardiac Surgery. Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1992.

- Spurlock, Jeanne. “Early and Contemporary Pioneers” in Black Psychiatrists and American Psychiatry. Edited by Jeanne Spurlock. 1st ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 1999.

- Terry, W. Scott. “A Missed Opportunity for Psychology: The Story of Solomon Carter Fuller.” Observer vol. 21 issue 6, June/July, 2008. https://www.psychologicalscience.org/observer/a-missed-opportunity-for-psychology-the-story-of-solomon-carter-fuller.

- Warren, Wini. “Dorothy Lavinia Brown From Orphan to Surgeon to Teacher” in Black Women Scientists in the United States. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2002.

- Weisse, Allen B. “Cardiac Surgery A Century of Progress.” Texas Heart Institute journal vol. 38 no. 5 (2011): 486-490. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3231540/pdf/20111000s00005p486.pdf.

- Writing Group on the History of African Americans and the Medical Profession. “African American Physicians & Organized Medicine: Acknowledging our Painful Legacy.” Slides presented at the National Medical Association, Sponsored by the American Medical Association. https://www.ama-assn.org/about/ama-history/history-african-americans-and-organized-medicine

MARIEL TISHMA currently serves as an Executive Editorial Assistant with Hektoen International. She has been published in Hektoen International, Argot Magazine, Syntax and Salt, The Artifice, and Fickle Muses. She graduated from Columbia College Chicago with a BA in creative writing and a minor in biology. Learn more at marieltishma.com.

Fall 2019 | Sections | Physicians of Note

Leave a Reply