Prasad Iyer

Timah Road, Singapore

|

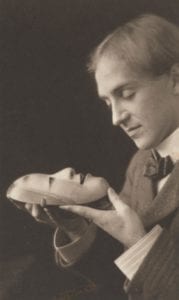

| H.J. Pollitt: Hypnotized. Frederick H. Evans. Early 20th century. Philadelphia Museum of Art. |

As a pediatric oncologist I have learned to put on an invisible mask before seeing my patients and their parents. I try to bring them some cheer and keep the enveloping darkness at bay, if only for a moment. The mask is also a shield to protect myself, lest my face reflect the whirlpool of emotion of the oncology ward. But I have learned over time that there are no masks of invincibility; the human face of the oncologist often lies exposed.

It was time for morning ward rounds and I braced myself. Seven-year-old Joshua, a precocious child with bright intelligent eyes, had been diagnosed with metastatic neuroblastoma when he was two. He received several rounds of chemotherapy, major surgery, stem cell transplantation, and radiotherapy followed by differentiation therapy over a period of two years. Every scan since his completion of therapy had provoked severe anxiety for his parents as well as his oncologist. Sadly, his disease had relapsed and his cancer-ravaged body lit up on his latest scans. We had run out of curative options; the focus would now be on palliation and comfort care. Science, medicine, and I had collectively failed Joshua and his family. Having known him for most of his life, I knew that he would see through any mask or cloak I could summon at that time. When I walked in to his room, he sized me up with his piercing stare and asked, “How will you remember me?”

The next patient was little Catherine, an effervescent five-year-old girl. She had been diagnosed with diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG) one year earlier. This type of brainstem tumor is a death sentence; modern medicine can only buy time. Catherine was on a cocktail of strong painkillers and fed with a nasogastric tube. Her little remaining time would be spent in a chemical haze trying to keep pain at bay. After a particularly stormy night of steroid-induced nightmares and an uncontrollable headache associated with vomiting, she was awake in the morning. When she saw me, she blurted out, “I want to go to heaven. I will miss my mummy and daddy but I can’t do this anymore.”

I squared my shoulders and went to see Zoe in the intensive care unit. She had aggressive leukemia that had relapsed after a stem cell transplant. There were no curative options left and she was fighting a serious infection. She was lucid and pain free for now. Her parents had been on vigil by her side through the last few days and nights. She looked up as I walked in and said, “I am trying my hardest to stay alive. Can you help me?”

Children’s insight, wisdom, and unfiltered expression can be completely disarming. When you have invested a significant amount of time and energy developing a rapport with patients and families and have gone through long months on the roller-coaster ride that is cancer therapy with them, you become more than just the family’s doctor. In their eyes you become an important and trusted team member coordinating the war against cancer. Keeping close enough, but maintaining a professional distance is a hard balance to achieve.

For me, letting go of the kids is the hardest part of being a pediatric oncologist. It goes against the grain of all my training. Children are not supposed to die. Facing the unfairness of it all consumes even the hardiest of professionals. Did I do right by my patient and their family? Re-visiting treatment decisions when things go wrong can haunt even the most resilient doctor. But embracing one’s human side is not weakness. It shows that you are invested in the well-being of your patients and their families. I have learned to accept that the suffering one witnesses daily will leave non-healing scars.

Maintaining equipoise at work is difficult as every word, facial expression, and body language cue is scrutinized by families. One minute you may be dispensing terrible news that will devastate a family, while the next patient you see could receive the all-clear from the latest scans. Balancing one’s own emotions whilst witnessing unbearable grief one minute and unadulterated joy the next is not something one can ever master. Dealing with and compartmentalizing these peaks and troughs takes time and effort.

Developing skills and strategies to combat burnout and workplace stress, balance emotions, and maintain professional boundaries requires insight, organizational guidance, education, and mentorship. Recognition and management of these issues is gaining traction and is being integrated in curriculum planning for trainees and at the organizational level. Fostering individual resilience is important. Peer support plays an important role in not only delivering good quality of care for the patient but also identifying a physician in need. Self-compassion and peer and family support, along with the ability to switch off from work-related stress, is essential to continue working in this high-pressure, high-stakes environment. This is vital for the professional’s mental health and paramount for delivering the best care possible.

PRASAD IYER, MD, FRCPCH, is a consultant paediatric haematologist-oncologist at KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital, Singapore. He is taking his first steps in creative writing. He grew up in India and trained in paediatrics and oncology in the United Kingdom. He believes he is a child of the world and loves to spend time travelling with his family.

Fall 2019 | Sections | Doctors, Patients, & Diseases

Leave a Reply