JMS Pearce

Hull, England, United Kingdom

|

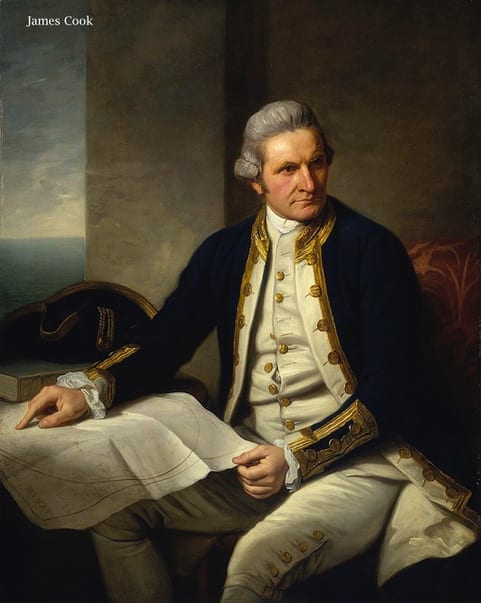

| Captain James Cook (1728-1779). Nathaniel Dance. BHC2628 |

Cures of disease are still relatively uncommon. Scurvy is an example of a disease well recognized but whose cause eluded doctors for centuries until an empirical curative remedy and later a specific cause were discovered. In more recent times Koch’s discovery of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in phthisis or consumption in 1882, and Marshall and Warren’s Helicobacter pylori in peptic ulcer in 1982 are analogous. There are many more.

The illness scurvy was observed but unnamed in the ancient writings of Hippocrates and Pliny. The English words scurvy, scurvy weed, scurvy grass, scuruie or scorbute, and scorbutic appear in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, but are recorded earlier by the Portuguese and others. Infantile scurvy was clearly described (conjoined with rickets) by Francis Glisson in his De Rachitide in 1650.

In his book,1 Stephen Bown credited a solution to the mystery of scurvy to three people: the naval surgeon James Lind (1716-1794), sea captain James Cook (1728-1779), and a physician, Gilbert Blane (1749-1843). Many if not most victims were mariners on voyages of exploration seeking valuable treasure and spices. Far more sailors died of scurvy than from warfare, storms, or other diseases. The first symptoms generally started some two to three months into the voyage, the time for ascorbic acid stores to be depleted.

Physicians of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries thought that sailors’ scurvy was caused by salt-preserved meats, fat skimmed from boiling pans, bad air, thickening of the blood, sugar, or melancholy; but no one knew for certain. It was known that once victims reached land they could recover by eating scurvy grass, wild celery, wood sorrel, nasturtiums, brooklime, or Kerguelen cabbage. However, citrus fruits were known to earlier explorers as both remedy and preventive for scurvy (scorbutus).

The important experiences of Lind are deservedly well known.2 Since the seventeenth century citrus fruits and even James Cook’s barley malt and unpalatable sauerkraut3 had been considered remedies for scurvy. But surprisingly the sailors’ diet, almost devoid of fresh fruit and vegetables, allowed scurvy to continue with thousands of deaths.

An apparent paradox is why the navy did not for over forty years implement James Lind’s 400-page Treatise on Scurvy published in 1753, especially since on the ship Salisbury he had performed a controlled therapeutic trial in 1747, which showed the striking benefits of oranges and lemons.2 Sir Gilbert Blane (1749-1834), physician to the Fleet, finally persuaded the Admiralty in 1795 to order that every sailor in the Navy be given three quarters of an ounce of lemon juice daily.1

|

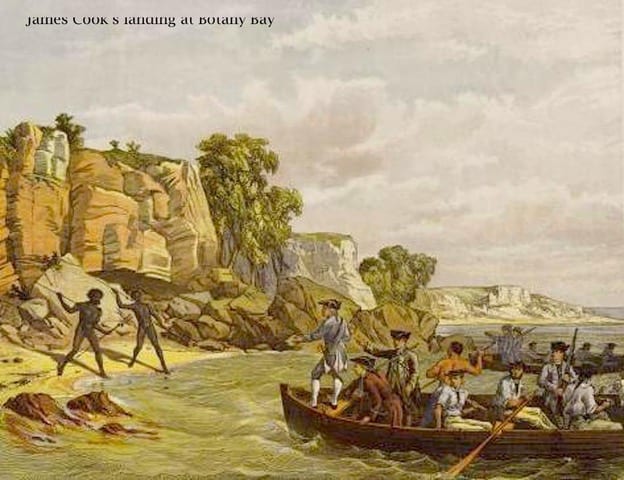

| James Cook’s landing at Botany Bay |

The crew of Admiral George Anson’s earlier 1740 voyage in Centurion to fight the Spaniards and secure treasure (mainly silver) suffered the ravages of scurvy. It temporarily abated when they landed in Juan Fernández Island that was replete with turnips, radishes, wild cresses, and sorrel, many of which are high in vitamin C. Nonetheless only 200 of the 400 crew members survived.

When James Cook from 1768 to 1771 navigated the almost uncharted Pacific Ocean, his first task was to record the rare transit of Venus across the sun. He sailed in a converted coal bark, the HMS Endeavour constructed in Whitby, on the Yorkshire coast. Its aim was to explore and chart the postulated Terra Australis Incognita. Antiscorbutic citrus fruits and fresh vegetables were not part of the ship’s diet. Many sailors suffered from scurvy, which was often fatal. Melancholy, a sense of isolation, and nostalgia were frequent and characterized by Thomas Trotter, MD, twenty years later as “scorbutic Nostalgia.”4 Cook forced then persuaded his reluctant crew to eat sauerkrauti and insisted on the collection of fresh vegetables at every port. His famous botanist Joseph Banks noted on 11th April 1769:

“The inside of my mouth which threatned to become ulcers, I then flew to the lemon Juice which had been put up for me according to Dr Hulmes method . . . every kind of liquor which I usd was made sour with the Lemon juice No 3 so that I took near 6 ounces a day of it. The effect of this was surprizing, in less than a week my gums became as firm as ever and at this time I am troubled with nothing but a few pimples . . . “5

In Cook’s first voyage scurvy was common, but records show his awareness of antiscorbutics though nobody knew how they worked. Scurvy was controlled by his sauerkraut, and when available by fresh vegetables and fruit. There were no deaths from scurvy.

It is of interest that the link between citrus fruits and scurvy was much earlier recognized in 1497 by the Portuguese Vasco da Gama, in 1593 by Richard Hawkins, and in 1614 by John Woodall.

|

| John Woodall |

Vasco da Gama

Two hundred and fifty years before James Lind’s treatise, Vasco da Gama managed to drastically reduce scurvy in his sea voyage. On July 8, 1497, Vasco da Gama set sail from Lisbon in search of a sea passage to India through the Atlantic Ocean. On Nov 7, after sixteen weeks at sea, none of the crew had developed scurvy—although the disease normally begins within two months of total absence of vitamin C.6 By January 11, the symptoms of scurvy devastated the crew. Some weeks later they arrived at Mombassa, where the King fed them oranges and lemons—due to which “some of our ill were cured of [‘escorbuto’] scurvy.” Da Gama then crossed the Indian Ocean and stayed in India for four months. On an arduous home journey without fresh fruit or vegetables many more succumbed to scurvy. When in January 1499 they anchored at Malindi, they asked for oranges. Nevertheless, fifty-five men died before their return to Lisbon. Jonathan Lamb wrote: “In 1499, Vasco da Gama lost 116 of his crew of 170; In 1520, Magellan in a three year voyage in 1519 lost 208 out of 230; mainly to scurvy.”7

Sir Richard Hawkins

Admiral Sir Richard Hawkins, in a voyage into the Southern Ocean observed that scurvy appeared in his crew in 1593, near Santos, in southern Brazil;8 he attributed the scurvy to seething of the meat in saltwater and advised as few salt meats in the hot country as may be. He reported that:

“There was great joy amongst my company and many with the sight of the oranges and lemons seemed to recover heart. This is a wonderful secret of the power and wisdom of God that hath hidden so great and unknown virtue in this fruit to be a certain remedy for this infirmity [scurvy].”9

Hawkins called scurvy “the plague of the Sea, and the Spoyle of Mariners.”

John Woodall

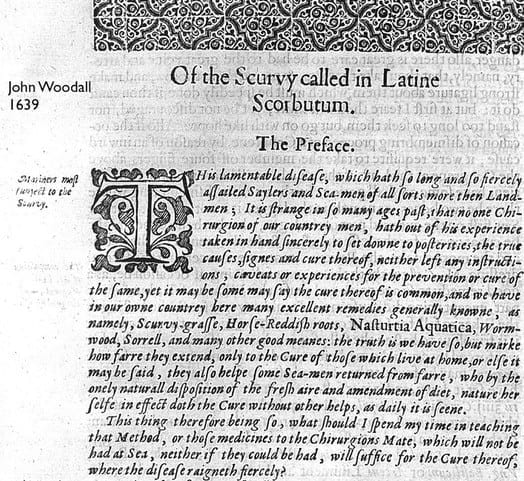

John Woodall (c.1570–1643) was a surgeon, chemist, linguist and diplomat. In 1599 he was admitted to the Barber-Surgeons Company of London. He worked as Surgeon General to the East India Company and acquired wealth by attending their sick and by “fitting and furnishing of their Chests with medicines and other appurtenances thereto.” His book The Surgeon’s Mate (1617)10 became the standard advice to all ships’ surgeons on medical treatments while at sea. It dealt with gunshot wounds, gangrene, and the plague. Importantly, it also contained a chapter (pp. 160-176) Of the Scurvy called in Latine Scorbutum (Fig 1.): an enlightened view of scurvy:

|

“Also note further that there are few diseases at Sea happeneth to Sea-men, but the Scurvie hath a part in them, the Fluxes which happen chiefly proceed from the Scurvie, and I suppose if Sea-men could be preserved from that disease, few other diseases would indanger them.”

Woodall advocated many herbs and remedies, notably:

“We have in our owne country here many excellent remedies generally knowne, as namely, ‘Scurvy-grasse, Horse-reddish roots, Nasturtia Aquatica, . . . Bay-berries, and Juniper berries, . . . juyce of Lemmons, of Limes, Citrons, and Oranges.’” But these were for those “living at home or close to it, sea-men returned from farre, who by their onely natural naturall dispositions of fresh aire and amendment of diet, nature herself doth the cure without other helps.”

He was elected surgeon at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital in 1616 where he was a colleague of William Harvey.

———

In 1928, Albert Szent-Gyorgyi (1893-1986) isolated from plants a compound (C6H8O6) that he named hexuronic acid, though suspecting it was Vitamin C, as later proved by Haworth. He found oranges and paprika were rich sources. In 1937, Szent-Györgyi received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his researches, including the role of vitamin C in preventing scurvy.

At the same time, in 1932 Charles Glen King of the University of Pittsburgh proved that vitamin C was the antiscorbutic agent (hexuronic acid, renamed ascorbic acid or vitamin C). The chemist Walter Haworth (1883-1950) determined the structure of vitamin C and synthesized it in 1932, for which he shared the Nobel prize in 1937.

End notes

- It has been calculated that this contained approximately 150 mg. vitamin C per week for each of the 95 men on board.2

References

- Bown SR. Scurvy: How a Surgeon, a Mariner and a Gentleman Solved the Greatest Medical Mystery of the Age of Sail. New York, St. Martin’s Press 2003.

- Pearce JMS. The Mysteries Of James Lind And Scurvy. Hektoen International. Physicians of Note. Fall 2016.

- Burnby J, Bierman A. The incidence of scurvy at sea and its treatment.Revue d’Histoire de la Pharmacie 1996; 312:339-346

- Vale, B., Edwards, G. (2011). The Conquest of Scurvy. In Physician to the Fleet: The Life and Times of Thomas Trotter, 1760-1832 (pp. 110-123 http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7722/j.ctt81v29.15

- Banks Sir Joseph. The Endeavour Journal of Sir Joseph Banks. [Journal from 25 August 1768-12 July 1771] A Project Gutenberg of Australia eBook No.: 0501141h.html

- Martini E. How did Vasco da Gama sail for 16 weeks without developing scurvy? The Lancet 2003;361:1480.

- Lamb, J. Preserving the self in the south seas, 1680–1840. University of Chicago Press. 2001. p.117.

- Anonymous editorial. The Observations of Sir Richard Hawkins, Knight, in his Voyage into the South Sea, Anno domini, 1593. Nutrition Reviews 1986;44:370-371. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1753-4887.1986.tb07575.x

- Carpenter K J. The History of Scurvy and Vitamin C. Cambridge University Press. 1988.

- Woodall J. Surgions mate, or A treatise discouering faithfully and plainely the due contents of the surgions chest. London: Nicholas Bourne 1617.

JMS PEARCE, MD, FRCP, is emeritus consultant neurologist in the Department of Neurology at the Hull Royal Infirmary, England.

Fall 2019 | Sections | History Essays

Leave a Reply