Göran Wettrell

Sweden

Within Western figurative pictorial art there has long been an interest in showing sick children, their psychological attitudes, the effects on the family, and indeed the very reality of disease. One of the best known works on this subject is by Gabriel Metsu (1629-1667) of the Dutch Golden Age of painting. Titled The Sick Child, it shows a pale, sick-looking girl in a pieta position in her mother’s lap.1 Significant symbols included in the background are a dark and blurred image of Christ’s deposition on the cross (Figure 1).

In the late nineteenth century, the scene of a sick child also became a more frequent object of Scandinavian painters such as Christian Krohg and Edvard Munch, both Norwegian artists, and also Carl Wilhelmson, of Swedish origin.

Christian Krohg (1852-1925)

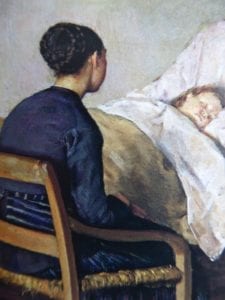

Already in 1880 the Norwegian painter Christian Krohg presented in Sick Girl a realistic and fragile message by the expression of her face and eyes (Figure 2). This is in contrast to the various white surfaces such as the pillow and the withering rose in the girl’s hands, both indicating a hopeless situation.1 Another painting by Krohg, Mother at the Bedside of a Sick Child of 1884 (Figure 3) shows more of a common everyday life situation with tranquility and hope in the girl sleeping on a prominent pillow.1 When Krohg produced these paintings he may have been affected by his sister Nana’s illness and death in 1868.1 He had experienced the same fate as Edvard Munch, having lost at a young age from tuberculosis both his sister and his mother.

Krohg had studied law at the University of Christiania/Oslo and also attended a local art school. Later he traveled and trained in Germany, Denmark, and Paris. He became the first professor-director at the Norwegian Academy of Arts in 1909. By focusing on everyday life, he became the local leading person in the transition from romanticism to naturalism.

Edvard Munch (1863-1944)

The painting of Krogh might have inspired Edvard Munch, the most celebrated Scandinavian painter of modern times. He, at the age of twenty-two, painted The Sick Child, the first version in 1885-1886.1,2, 3 The object was a début and was criticized as a rough draft. Over the years it was followed by another five paintings with the same motif of the sick child, as well as several lithographs, drypoints, and etchings illustrating the theme.

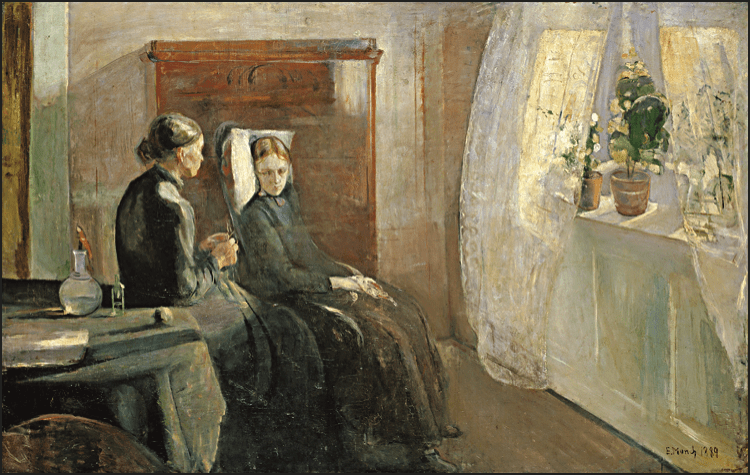

The six paintings have the same composition but vary in their colorization, with gray-white and dreamy light black dominating in the initial 1886 version but later changing to touches of green, yellow, and reddish. Over time the colors became more intense. The paintings express emotional feelings, and the subjectivity of the painter is expressed with harsh vertical brush strokes. In the composition, the girl in profile is shown pale and indistinctly staring far away. The artist’s sister died of tuberculosis at age fifteen and his mother died of the same disease when Edvard Munch was only five years old. The girl is supported by an older woman, dressed in black, bowed and depressed. The girl and woman are joined by dim hands, positioned in the centrum of the work. Common peripheral attributes are shown such as a bottle on a table and on the opposite side a glass (Figure 4).

Christian Krohg, 1884, National, Musuem of Art, Oslo

The first version of the sick child took over a year to complete and the painting was scrubbed and repainted before the final version. It was first exhibited in 1886 at the Autumn Exhibitíon in Christiania/Oslo and was criticized as an unfinished work. In 1889 a new version was ordered by a Norwegian admirer and painted in Paris. In 1907 still another version of the sick child was made for the Swedish benefactor and banker Ernst Thiel. A painting of his sick sister, less dramatic and more conventional, was produced in 1889. It was probably done in response to some of the critics of his first painting finding it unfinished and unskilled.1 The title is Spring and the air and the light come through the window where the flowers are growing. The girl looks sick and pale, and holds a bloody handkerchief in her hands (Figure 5).

Munch split most of his time during 1892-1908 between Paris and Berlin. Though initially drawn to impressionism or post-impressionism, he turned with the first version of The Sick Child to symbolism and expressionism.2, 3 Most of his works might be referred to as the style known as symbolism, where it became important to find ways to dramatize emotional experiences on the theme of death, life, and sex relations.

Carl Wilhelmson (1866-1928)

During the years 1890-1896 Carl Wilhelmson studied painting at the Academie Julien in Paris.4, 5 He spent, however, most of the summers visiting his mother in Fiskebäckskil on the west coast of Sweden. During these summers he found his motif in the small houses of the fishing community. In 1894 he had a breakthrough painting and was illustrating the light and color of the life of the common west coast working people.

In the summer 1896 Carl Wilhelmson painted The Sick Child as part of a series of indoor pictures with a message on illness and death. The realistic painting was arranged in his mother’s home. His mother, Mathilda Wilhelmson, is bending over the child. The painter’s sister, Anna, is standing at the door. On a stool a friend of the family, Emma Christensson, is leaning on her hand. There is also a chair with a bottle of medicine. The painting is realistic, with a composition of light coming from behind through the door opening. The painting of The Sick Child was exhibited at the Salon in Paris. It was reviewed by the painter Ivan Aguéli in a positive way in a French paper, and described as genuine, intimate, and plain with pure colors in gray, green, brown, and an intense silver light. The indoor pictures during 1894-96 were about his childhood and his work at his mother’s home. Far from creating a new style, he acquired his imprint of national romanticism from his west coast origin and was mainly influenced in Paris by the neoimpressionistic theory of color. He also developed an impressive technical skill. After the period of indoor pictures, he turned to a more monumental style with landscapes but with the human being still in the center. In 1897 he returned to Gothenburg as a teacher at the Art School of Valand. He became a member of The Swedish Artist’s Union and ended his career as professor in painting at the Royal School of Art in Stockholm.

The pictures presented here convey a feeling of malady emanating from these sick, young children in the context of the historical and social factors of the time. An appreciated object for painting during the late nineteenth century was the pale, sick girl and the white pillow. Edvard Munch wrote in 1930: “As for the sick child, it was the period I think of as The Age of the Pillow. Many painters did paintings of sick children on their pillows.”3 One important aspect Munch was referring to was tuberculosis, estimated during the nineteenth century to be responsible for causing every fifth death and making obvious the reality of the disease and the chance of death. By thus depicting illness in art it allows us to see it as more than its mere biological aspects. Edvard Munch explained and wrote: “Nature is not only all that is visible to the eye . . . it also includes the inner pictures of the soul.”

References

- Bordin, G. and D’ Ambroso, LP. (2010). Medicine in Art. Los Angeles. The J Paul Getty Museum. p. 64-68, 311-320, 361-375.

- Fredlund, B. Edvard Munch at Gothenburg Art Museum. (2003). Uddevalla. Göteborgs Konstmuseum. ISBN – 9187968509. p. 8-18, 68-69.

- Https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The 2019-10-11.

- Welander- Berggren, E. Carl Wilhelmson. Waldemarsuddes utställningskatalog nr 93:09. Värnamo. Fälth och Hässler. ISBN 978-91-86265- 00-7.p. 54, 133-142.

- Https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carl 2019-10-11

GÖRAN WETTRELL, MD, PhD, FLS, is an Associate Professor and Senior Consultant in Paediatric Cardiology and Paediatrics at Lund University, Sweden with interest in paediatric pharmacology, molecular genetics, and primary arrhythmias. Other interests include male choir singing, traveling, and the medical humanities.

Leave a Reply