Rasa Rafie

Colorado, United States

|

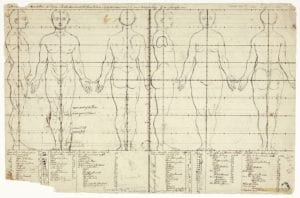

| Copies after Illustrations of Statues and Paintings (recto); Measurements for a Man’s Skeleton (verso). After Gerard de Lairesse. N.d. The Art Institute of Chicago. Public Domain. |

In college, we were the top of our class, the winners of scholarships and awards, the leaders of campus organizations. We were the ones our classmates looked up to and the names our teachers used as examples. We worked hard and those efforts delivered results—good grades, MCAT scores, and finally medical school.

In medical school, things do not work out this way. Working hard is no longer enough, being smart is no longer enough. Why? Because everyone works hard and is just as smart as you are. Medical school takes the top students of every class and puts us all together. Naturally, we cannot all still be the best.

I knew this—but as anatomy class started, I could not help but feel I was behind everyone else. Through bone labs and small group sessions, I started to realize that my classmates did not seem to be like me. It seemed as if all of them had a background in anatomy already, either a master’s degree, a position as a teaching assistant, or undergraduate coursework experience. Was I the only one that had no experience? In class, my self-confidence plummeted. My classmates were answering questions from yesterday’s lecture, when I was barely reviewing last week’s. Why was I not getting this? Why was I different?

Because of my lack of experience, I spent more time in the cadaver lab than my more experienced classmates. During those times, I started seeing the same ten to fifteen students. They were doing just as many tutoring sessions, just as many early mornings, and just as many late nights. I saw them in the library, like me, with deep set, sleep-deprived eyes and several coffee mugs and, although we were not friends, I felt a connection with these classmates. Maybe they felt like I did.

At the end of week two, on one of those Saturday nights in the cadaver lab, I asked one of my classmates if she wanted to study together—after all, we were the only two in the lab. As we memorized and tested each other on the muscles of the upper limb, we shared stories about how tough the last two weeks had been for each of us. I felt shocked. The words coming out of her mouth were the same ones I had shared with my mom just a few nights before: “I don’t know if I can do this. I don’t know if I belong here.” Like me, she too was feeling the first symptoms of imposter syndrome.

The truth is, we do belong here. I went to graduate school and she graduated top of her class. Somewhere along the line, we lost sight of these strengths. That night, through our discussion, she helped me rediscover mine and I believe I helped her do the same. Over our tank, we made a pact to not compare our journey to those of others. We promised to remind the other of this in times of doubt and fear—and to never forget what a privilege it is to work with the human body.

Through this experience, I gained more than knowledge about the anatomy of the human body. I gained an intense and deep-rooted gratitude for its fragility, an appreciation for the variety, and a humble realization of the orchestra that happens each day inside every one of us—the orchestra of systems that allows us to breathe, to taste our favorite foods, to sing at the top of our lungs, to dance at our weddings, and to feel emotion. Seeing the complexities of a body moved me in a way textbooks never could.

This was someone’s father—someone’s child—someone’s lover. I reminded myself every day.

As I look back now, a month away from completing my first year of medical school and with ten months of anatomy under my belt, I recognize I was wrong. It was not a curse that I had no anatomy experience coming into medical school, but rather a special learning opportunity. I am walking away today as a more empathic person. At my core, I see the values of treating with care, understanding, compassion, patience, recognition—and meeting each of my patients where they are at.

Because one day, those values made all the difference for me.

RASA RAFIE, MS, is a second-year medical student in Colorado. Prior to medical school, she attended the Keck School of Medicine at the University of Southern California where she received her Master’s in Science in Global Medicine. Her global health experience includes studying sugar consumption in the Mamanuca island of Fiji, IV drug use in Brazil, a field study at the United Nations, and additional trips to Honduras and China. As a first-generation immigrant, Rasa believes that cultural competency, diversity, and advocation are an integral part of medicine today and hopes to spread these values through her other passions of the medical humanities and spoken word.

Highlighted Vignette Volume 13, Issue 2– Spring 2021

Leave a Reply