The Dean’s December, published in 1982, is a highly autobiographical book written by Nobel Prize winner Saul Bellow.1 It is about the experiences of a university Dean and is divided into two episodes.2 The first takes place in Bucharest, where the Dean visits his mother-in-law, once a prominent but now politically disgraced party member lying helpless in intensive care:

“So she was hooked in now to the respirator, scanner, monitor. The stroke had knocked out the respiratory center, her left side was paralyzed. She couldn’t speak, couldn’t open her eyes. She could hear, however, and work the fingers of her right hand. Her face was crisscrossed every which way with tapes like the Union Jack . . .”

In order to be allowed to approach her,

“you had to put on a sterile gown and oversocks, huge and stiff. Also a surgical cap and mask. Valeria understood that her daughter had come, and her eyes moved under the lids . . . she answered by pressing her fingers . . . her son-in-law had never before seen her hair down, only braided and pinned. . . . He would never have guessed this fine white hair to be so long. There was also a big belly. Beneath it her thin legs. That, too, was painful to see. . . . He wanted to cry, as his wife was doing.”

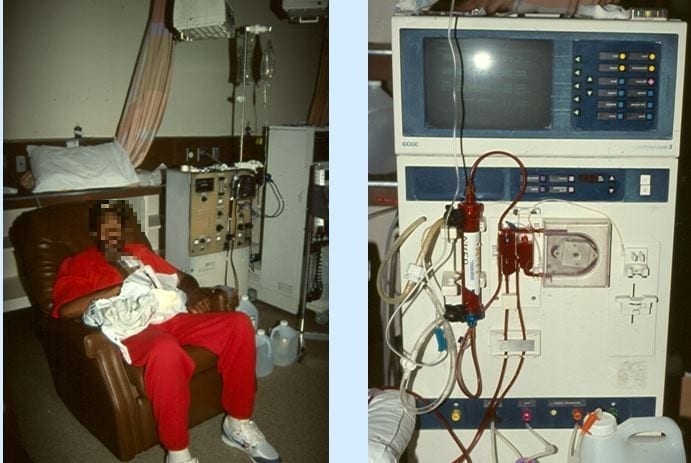

The second episode was intended to be published in a national magazine but apparently was rejected and Bellow used it for a scene that takes place in the old Cook County Hospital in Chicago. A Filipino nurse guides him through old tunnels, where pipes drip rusty water, blood is encrusted on the walls, and he is taken to the dialysis room:

“We stand and watch the purification process. Hooked into a machine, a large black man in worn work clothes is only semi-conscious. . . . The small woman whispers to me. Kidney patients seldom sleep well, and while their blood is being cleansed they sometimes fall into a stupor. The process takes four hours to complete. . . . Kidney patients look puffy. The legs and arms of the veterans are disfigured by surgically produced fistulas. Blood vessels are fused to increase circulation and these conjoined or grafted veins and arteries make great painful lumps. . . . A woman is now brought in who can no longer be treated through the arms or the legs. Her fistula is on the chest. . . . an even older man is brought in who looks altogether senseless. The guide whispers to me: “Dementia – not with it.”

The technician, a Chinese woman, works with beautiful skill,

“washing the lumpy arm with disinfectants, then plugging in the tubes, light and quick, no signs of pain from the old man. But then she blunders. A valve has been left open on the tray, and immediately everything is covered with blood. The suddenness of this silent appearance and the volume of blood with which the tray fills makes my heart go faint. I am almost overcome by a thick and sweet nausea, as if my organs were melting like chocolate in hot weather. . . . The Filipino nurse says, ‘You are a little pale. Do you want to go?’”

The social worker who accompanied Mr. Bellow reported that during his visit the famous author indeed looked faint and pale. But in the book he comments that it was not only the blood, but that these people pin their hopes on kidney transplants that will never happen and that they are dead men and women. He noted that the nurses and attendants were curiously emotional and extraordinarily tender, manifesting “a wonderful but also amorphous pity, a powerful but somehow indiscriminate love for these people.”

References

- Saul Bellow: The Dean’s December. Harper & Row, Publishers, New York, 1982.

- George Dunea, “Depression on both sides of the Iron Curtain,” British Medical Journal. 1982; 285:1551 (27 November)

|

GEORGE DUNEA, MD, Editor-in-Chief

Fall 2019 | Sections | Nephrology & Hypertension

Leave a Reply