F. Gonzalez-Crussi

Chicago, Illinois, United States

|

| Figure 1. Right section of an etching titled Infirmus eram et visitastis me: (“I was sick and you visited me,” quoted from Matthew 25:36), sometimes attributed to Cornelius Galle. The left section (not shown) has Jesus Christ overseeing the hospital visit. |

Among the many species of adversity that unavoidably befall us during life, to become a hospitalized patient is not the slightest. Today, hardly anyone is exempted: life begins and ends inside hospital quarters. We are born in some obstetrics suite and die amid beeps of life-supporting equipment, the hiss of oxygen tanks, and the drip of IV solutions: such are today’s “technological last rites.” And between life’s beginning and its end, it is appointed that we must visit one or more times the hospital premises. We arrive there under apprehension concerning our future, not knowing what will happen to us. We hear that inmates are sometimes harmed by neglect or incompetence of the staff; that the wrong medication may be given, the needed one omitted, or either one administered in harmful, sometimes fatal doses. We would rather not go. Yet, I wish to argue that all of us, without exception, are already hospitalized—in a metaphoric sense—without realizing it.

It was not always so. There were no hospitals in Greco-Roman antiquity.1 Ancient civilizations had places where priests subjected the sick to magico-religious rituals, but none had public institutions devoted to the long-term care of the sick.2 Scholars agree that the public hospital as a place where the sick and poor could be received and cared for arose and expanded in concert with the rise of Christianity.3 However, the nature of the hospital has changed spectacularly in the course of history. Those founded under the aegis of monastic orders or through pious bequests of the rich during medieval and Renaissance times, offered excellent spiritual care, but attention to the body was found wanting. Hygienic conditions were dismal; those admitted cohabited with the indigent and the insane. An engraving based on a painting by the Flemish artist Maarten de Vos (1532-1603) shows a crowded ward where pious visitors feed the inmates or supply medicines unsupervised. In the foreground, a woman in crutches seems to meditate sadly on her predicament; to her right, a visitor gives some medicine to a patient with a skin eruption. In the distance, a physician appears to be examining a sample (Fig. 1).

Superstition and irrationality informed medical theory. Eminent medieval intellectuals who advocated knowledge based on experiment and reason, believed nonetheless in pathology produced by exposure to moonlight, menstruating women, and the “evil eye.”4 Such preposterous notions persisted well beyond the Renaissance. Worse yet, as medical professionals gained in prestige, the sick and poor had to contend with medical hubris. A drawing of those times shows a physician refusing to treat a rebellious patient (Fig. 2). For a long time, hospitals spread infectious diseases: to wit, the infamous, well-known instance of deadly “childbed fever,” spread by Dr. Ignác Semmelweis from patient to patient as he examined them with contaminated, unclean hands.

In sum, the very existence of hospitals could be seriously questioned in the past, since they did more harm than good. Indeed, only the destitute ended in a hospital; those who could afford it preferred being treated at home. Nineteenth century surgeons performed bloody surgical procedures in the drawing-rooms or private chambers of the well-to-do.

Fortunately, these are things of the past. Going to the hospital no longer feels like crossing the gateway to death. Today’s health centers seem eons away from the appalling medieval institutions that housed only the pitiable, marginalized elements of society: orphans, beggars, vagabonds, prostitutes. Modern hospitals have become centers of advanced medicine, “the headquarters and power base of the medical élite,”5 where cutting-edge medicine is practiced. Furthermore, amenities are now considered an important component of a patient’s experience and, allegedly, of clinical outcomes. Experts claim that people willingly “trade off clinical quality for a very pleasant experience.”6 Accordingly, hospitals offer private, family-friendly rooms, walls in soothing pastel colors, great views, massage, and other amenities worthy of a luxury hotel—and no less costly! Yet, all of this does not make the hospital a desirable destination. We would rather not go. Whenever possible, we refuse to go.

However, the artistic imagination perceives hospitalization as immutable human fate, and this literary conceit is no better expressed than in a short story by the Italian writer Dino Buzzatti (1906-1972), titled “Seven Floors” (Sette Piani).

|

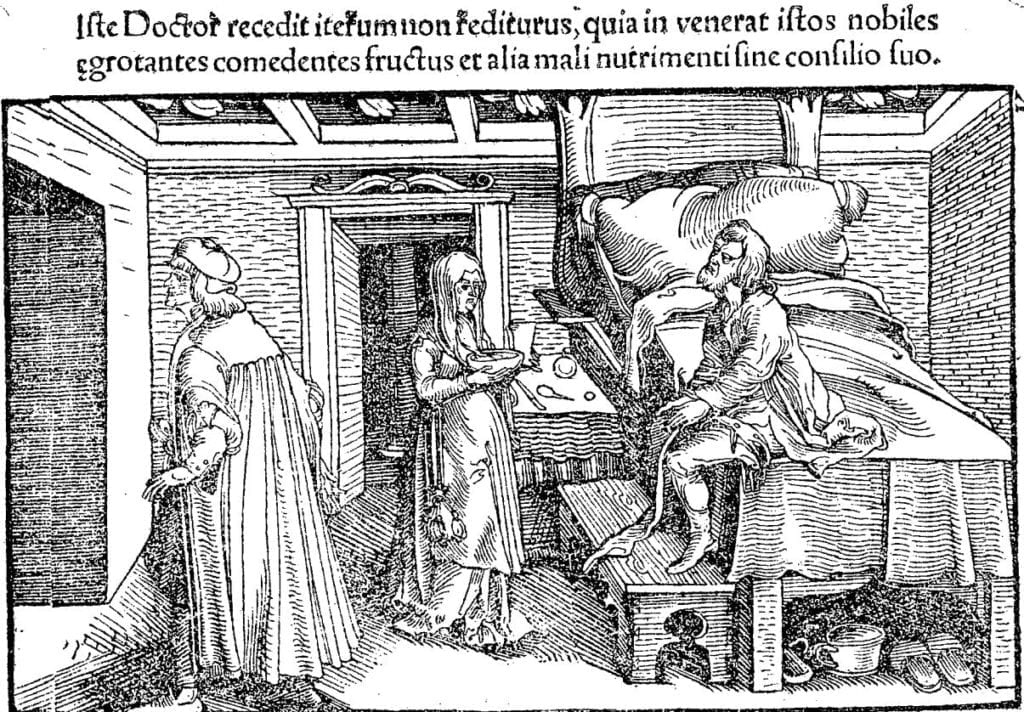

| Figure 2. Dignified doctor leaving a patient’s bedroom. The legend says: “He will not come back, because he found these noble persons eating, despite his advice, fruits and other aliments difficult to digest.” Wood engraving from the Spanish book of Luis Lobera de Avila Banquete de Nobles Caballeros (1530). Digitized by the Biblioteca Digital Hispánica, Biblioteca Nacional de España. |

In the story, a Mr. Corte checks into a hospital with a trivial malaise. The hospital has seven floors. Patients with minor illnesses are admitted to the top floor; those with more severe conditions to lower levels, progressively lower as the disease is deemed graver. Corte, whose illness seems slight, goes to the seventh floor. Inmates there can discern through the windows the first floor, which they fear: it is a dark, silent, sinister tier reserved for those about to die.

Corte’s health apparently does not change, but a “surrealist,” absurd sequence of external circumstances determines his inexorable, gradual transfer to lower and lower floors. A mother and her children need to stay together, but there are no available beds. Would Mr. Corte mind yielding his place to the lady? Of course, this would be only temporary. He accepts and is transferred one level down. A minor skin lesion appears that must be seen by a specialist who works on a lower level. Mr. Corte must go down once again. He is informed that the best machines to treat his condition are emplaced in a still lower storey; his downward translocation is necessary. While on the third floor, a purely administrative matter displaces him again: the staff is going on vacation and the ward must close. Since the patient beds are few, they will be consolidated with those of another floor. “The third floor patients joined with those of the fourth floor?” asks Corte anxiously. No, those of the third floor must go down to the second. Corte, pale as a bedsheet, is dismayed. But he is told that there is nothing to worry about: as soon as the staff comes back from vacation, the patients will be returned to their normal places. On each new displacement, his anguish grows, but the doctors have only soothing words and reassurances that everything will be all right; that they agree he is placed on a floor inferior to that which corresponds to his health condition, but this anomalous situation is accidental, transitory, and soon to be changed.

Change does occur one day, when attendants arrive carrying a duly signed order to take Mr. Corte to the first floor: his final transfer! The story closes as the curtains are drawn shut and the light is turned off in the first floor: the very spectacle that patients in the upper floors usually surveyed with a shudder.

The symbolism of this masterful short story is transparent. Life is Buzzati’s oneiric-surrealist-nightmarish hospital. We come into the world with a surplus of vitality, which warrants our ingress to the topmost floor, but hence the only possible progress is downward. In the course of our descent, sometimes we encounter those in worse shape than us. We can then brag that we do not belong in the same tier; that we are there only fortuitously, by sheer happenstance. But mark that no matter what we do, we shall be transferred to lower and lower floors. We may dutifully exercise, eat right, avoid all bad habits, and eliminate stress as far as possible. Still, we shall─ineluctably─ find ourselves ever closer to the ground-floor with each passing year. A force greater than any human agency will transfer us, and there is nothing we can do to stop it. Until one day, like Mr. Corte, we will feel invaded by a strange torpor; the sun may be shining outside, but the window blinds, “obeying a mysterious command,” will descend slowly, and completely block the light rays from entering our room.

References

- Roy Porter: “The Hospital”. Chapter Five in: Blood & Guts. A Short History of Medicine. W. W. Norton, New York, 2004, p.135.

- Michele Augusto Riva et al.: “The charity and the care: the origin and the evolution of hospitals.” European Journal of Internal Medicine. 24: 1-4, 2013.:

- George Parker: “The Early Development of Hospitals (Before 1348).” British Journal of Surgery 16 (nl. 61): 39-50, July 1928.

- Stephen R. Ell. “The Two Medicines: Some ecclesiastical concepts of disease and the physician in the High Middle Ages.” Janus 68 (1-3): 15-25, 1981.

- Roy Porter: “The Hospital” (Op. cit.).

- Pauline W. Chen: “How does your hospital room make you feel?” The New York Times December 10, 2010.

FRANK GONZALEZ-CRUSSI, MD, is a retired pathologist and emeritus professor of pathology at Northwestern University medical school, and the author of numerous medical and literary publications, as can be found on Wikipedia.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 12, Issue 1 – Winter 2020

Summer 2019 | Sections | Literary Essays

Leave a Reply