Sylvia Pamboukian

Moon Township, PA

An isolated village, a series of mysterious deaths, a mob in the graveyard at midnight—it sounds like the climax of a thrilling vampire story. However, these events occurred in 1892 Rhode Island at the gravesite of tuberculosis victim Mercy Brown five years prior to the publication of Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897). And it was not a group of pitchfork-wielding villagers but Mercy’s own family and friends who gathered in the gloaming, desperate to save Mercy’s brother, Edwin. Edwin was dying of the family curse—tuberculosis (also called consumption). The disease had taken Mercy’s mother and sister several years earlier. When newly married Edwin developed symptoms, he was duly shipped off to a sanatorium in Colorado Springs, but he returned home after two years no better. Meanwhile, teenaged Mercy developed galloping consumption and died in months. His family of five winnowed down to two, Mercy’s father was desperate. If the modern sanatorium had not worked, perhaps folk wisdom might. Encouraged by his neighbors, George Brown decided to exhume his loved ones to search for a still-bloody heart. Folklore declared that the dead relative with a bloody heart must be sucking the life-blood from Edwin, who could be cured by burning the offending heart to ashes then drinking the ashes in water. Only recently buried, Mercy’s heart was unsurprisingly judged the bloodiest, and the folk remedy was accordingly administered.1

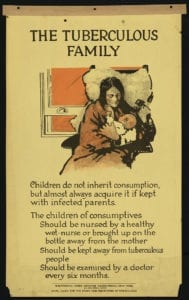

If George Brown’s motive was understandable, his actions seem far-fetched, even ghoulish. After all, this was the America of intercontinental trains, department stores, steel mills, and subways. Big-city newspapers of the time were mortified to report upon such an ignorant ritual taking place in a land of discovery and progress.2 Moreover, Robert Koch had identified the bacillus that causes tuberculosis in 1882, a full decade earlier. Sanatoriums, like the one Edwin attended, had offered up-to-date treatment consisting of rest, fresh air, and good nutrition since 1885.3 In addition, the National Tuberculosis Association (later American Lung Association) had launched a public health campaign offering the latest medical information about tuberculosis prevention in 1889.4 However, tuberculosis cures remained unreliable at best. Whether their course was slow (like Edwin’s) or fast (like Mercy’s), tuberculosis’s well-known symptoms were still greeted with fear and dismay: coughing, pain in the chest, loss of appetite, weight loss, night sweats, fever, chills, and fatigue.5 Because of its fearsome reputation, tuberculosis was ripe for metaphorical representation. Accordingly, Susan Sontag identifies several Romantic metaphors for tuberculosis as a disease of passion, melancholy, and passivity.6 Tuberculosis could also be linked to more malevolent narratives. For example, Clark Lawler links vampirism and consumption—both the revenant and the consumptive sharing qualities of pallor, thinness, lassitude, and blood.7 As in Mercy’s case, tuberculosis was linked not only to coughing blood but to sharing blood within a family.8 Unlike our familiar myth of the seductive stranger, vampires prior to Dracula were often depicted as exclusively or least preferentially feeding upon their own (often long-lost) kin as in Sheridan Le Fanu’s “Carmilla” (1872), the anonymous “The Mysterious Stranger” (1860) and Aleksey Tolstoy’s “The Family of the Vourdalak” (1839). After all, the discovery of a bacillus hardly satisfied turn-of-the-century minds as to why one family was so heavily afflicted while another was untouched: blood offered a more satisfactory explanation. A generation later, a National Child Welfare Association poster called “The Tuberculous Family” was still trying to persuade Americans that children did not inherit the disease through the blood but caught it from infected family members who failed to distance themselves from kin, implying that the infected were wrongly putting old-fashioned family ties above modern medical principles.9 A vampire story from turn-of-the-century New England highlights the ongoing faith in blood and family as the cause of tuberculosis and perhaps offers some insight as to why breakthroughs like Koch’s so often fail to put such faith to rest.

Thicker Than Water

A graduate of Mount Holyoke Seminary (now College), Mary E. Wilkins Freeman was a New Englander who often depicted the clash between traditional folkways and modern opportunities in her “local color” short stories.10 In “Luella Miller” (1902), the eponymous heroine (or villain) is suspected of draining the life from her family and servants, at least according to aged neighbor Lydia Anderson. Pale and weak, new bride Luella arrives in town “a slight, pliant sort of creature” like a willow.11 Lydia is quick to point out that the appearance of weakness may be deceptive: the pliable willow outlasts many hardwoods. Shortly after his marriage to sickly Luella, healthy Erastus Miller “went into a consumption of the blood,” a suspicious circumstance to Lydia since consumption did not run in his family.12 After his death, Erastus’s sister, Lily, comes to live with Luella Miller until Lily, too, weakens and dies. Lily is succeeded by her Aunt Abby, who in turns “begins to droop.”13 Shortly afterward, Abby is “white as a sheet” and “gasping.”14 As in the Mercy Brown case, vampirism in this story afflicts member after member of a single family, leaving them pale, fatigued, and breathless. The victim’s vitality seemingly nourishes the familial vampire—despite her ongoing weakness, Luella is never as sick as her kin. When Abby’s married daughter hears of her mother’s condition, Mrs. Sam Abbot returns to town to confront Luella about her baleful effect on the Miller family. A soft-hearted doctor warns Mrs. Sam Abbott not to agitate so weak a woman, but Mrs. Sam Abbot retorts, “Weak? It was my poor mother that was weak: this woman killed her as surely as if she had taken a knife to her.”15 Her full married name reminds us that Mrs. Sam Abbot is not a Miller anymore. She resides far away with her husband’s kin. Similarly, neighbor Lydia is no kin to Luella and is unaffected. At times, Luella seems unaware that she is harming others; however, like Mercy, she is blamed for not only spreading disease but thriving at others’ expense. As a wife, Luella’s proper role was to care for others, not demand care herself. Impatient with Luella’s malingering, Lydia concocts a home remedy of valerian and forces Luella to drink it: “You swaller this right down.”16 The italics, the intensifier right, and the country pronunciation of swaller betray Lydia’s impatience. Moreover, valerian was not used to treat tuberculosis or blood disorders: it was a folk remedy for nervous conditions.17 As in the Brown case, a home remedy is the last resort after the modern doctor can neither save Abby nor cure Luella. After the death of her second husband (the soft-hearted doctor) and her last servant from the village, Luella finally dies alone, without the caregivers and kin who sustained her.

The Tubercular Vampire

Published five years after Dracula, ten years after the Mercy Brown case, and twenty years after Koch’s discovery, “Luella Miller” exemplifies the ongoing connection in rural New England between blood and tuberculosis. If tuberculosis narratives have long been read metaphorically, vampire stories have also served various metaphorical purposes. But the tubercular vampire inhabits different metaphors than the Transylvanian nobleman. Where the male aristocratic vampire lords over his village, the female consumptive vampire is scapegoated by her neighbors. The village’s attitude toward Luella points to differing expectations about illness in men and women, just as Edwin and Mercy received different treatment for the same disease. Where Edwin remained a Brown after his marriage, women in this story are identified wholly with their husband’s kin. Although Luella married into the Miller family, she is treated as a Miller, not a Hill (her original name). Born a Miller, Mrs. Sam Abbot is treated as an Abbot. This is why Luella receives such powerful family affection, drawing Millers one-by-one to live with her. Far from a glamourous outsider, the tubercular vampire brings out disease within close-knit kin (and perhaps live-in servants). She is familiar instead of exotic, familial instead of sexual, and workaday instead of aristocratic. When no kin are left, Luella dies. Edwin Brown was similarly unlucky: despite the ritual at Mercy’s grave, he died.18

As these narratives indicate, neither folklore about nor folk medicine for tuberculosis disappeared after Koch’s breakthrough. The tubercular vampire’s emphasis on blood and on family proved much harder to stake than public health departments imagined, returning and returning long after progressives thought the matter dead and buried. If not eradicated, the tubercular vampire was diminished by competing vampire narratives that emphasized contagion rather than kinship. Apparently, the only remedy for a pernicious story is an even-more-pernicious story. If some imagine medical progress as an arrow flying from breakthrough to breakthrough, literature and folklore reveal a more recursive pattern in which engrained social beliefs live on long, long after their supposed demise.

End notes

- Michael Bell, Food for the Dead: On the Trail of New England’s Vampires (New York: Carroll and Graf, 2001), 20-22.

- Bell, Food for the Dead, 38.

- Catherine A. Paul and Alice W. Campbell, “Tuberculosis,” Virginia Commonwealth University Social Welfare History Project, last modified May 1, 2019, https://socialwelfare.library.vcu.edu/issues/poverty/tuberculosis/

- Bell, Food for the Dead, 25.

- “Tuberculosis (TB) disease: Symptoms and Risk Factors,” Centers for Disease Control, Department of Health and Human Services, last modified January 24, 2019, https://www.cdc.gov/features/tbsymptoms/index.html

- Susan Sontag, Illness as Metaphor (New York: Ferrar, Straus and Giroux, 1978) 25.

- Clark Lawlor, Consumption and Literature: The Making of a Romantic Disease. (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007) 188.

- ibid

- Paul and Campbell, “Tuberculosis.”

- “Mary E. Wilkins Freeman,” Loyola University Chicago Digital Special Collections, Accessed September 16, 2019. http://www.lib.luc.edu/specialcollections/exhibits/show/autograph-collection/mary-e–wilkins-freeman

- Mary E. Wilkins Freeman, “Luella Miller” in Dracula’s Guest, ed. Michael Sims (New York: Walker and Co., 2010), 392.

- Ibid, 393.

- Ibid, 395.

- Ibid, 396.

- Ibid, 400.

- Ibid, 397.

- Rebecca L. Johnson, et al, “Valerian,” in Guide to Medicinal Herbs, ed. Rebecca L. Johnson et al (Washington, DC: National Geographic, 2012), 53.

- Bell, Food for the Dead, 38.

References

- Bell, Michael E. 2001. Food for the Dead: On the Trail of New England’s Vampires. New York: Carroll and Graff.

- Johnson, Rebecca L. et al. 2012. “Valerian.” In Guide to Medicinal Herbs, Edited by Rebecca L. Johnson et al, pp. 53. Washington, DC: National Geographic.

- Lawlor, Clark. 2007. Consumption and Literature: The Making of a Romantic Disease. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- “Mary E. Wilkins Freeman.” Loyola University Chicago Digital Special Collections. Accessed September 16, 2019. http://www.lib.luc.edu/specialcollections/exhibits/show/autograph-collection/mary-e–wilkins-freeman

- National Child Welfare Association. “The Tuberculous Family.” New York, 1920-23. Accessed September 18, 2019. Library of Congress Online Catalogue. http://www.loc.gov/pictures/resource/ds.06489/

- Paul, Catherine A and Alice W. Campbell. “Tuberculosis” Virginia Commonwealth. University Social Welfare History Project. Last Modified May 1 2019. https://socialwelfare.library.vcu.edu/issues/poverty/tuberculosis/

- Sontag, Susan. Illness as Metaphor. 1978. New York: Ferrar, Straus and Giroux.

- “Tuberculosis (TB) disease: Symptoms and Risk Factors” CDC, Centers for Disease. Control, Department of Health and Human Services. Last Modified 24 January 2019 https://www.cdc.gov/features/tbsymptoms/index.html

- Wilkins Freeman, Mary E. “Luella Miller” Dracula’s Guest, edited by Michael Sims, pp. 391-405. New York: Walker and Co., 2010.

SYLVIA A. PAMBOUKIAN, Ph.D., is a professor of English at Robert Morris University near Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. She is the author of Doctoring the Novel: Medicine and Quackery from Shelley to Doyle as well as recent articles on nursing in Jane Austen and teaching the medical humanities. Her upcoming book project is about poisoning in literature.

Submitted for the 2019–2020 Blood Writing Contest & Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 12, Issue 2 – Spring 2020

Leave a Reply