Stanford Shulman

Chicago, Illinois

|

| Fig. 1 N Corvisart, F.X Bichat, and Rene Laennec are each shown on a commemorative postage stamp of France. From the author’s collection of medical history stamps. |

Introduction

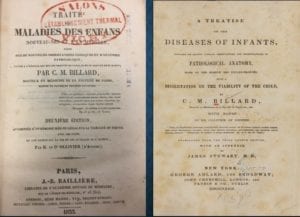

During the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries medicine transitioned into a more science-based discipline. This was primarily the result of gross pathology contributions of Giovanni Morgagni (1682-1772) of Padua and the later efforts of French physicians Jean Corvisart (1755-1821), F.X. Bichat (1771-1802), Rene Laennec (1781-1826), (Fig. 1) and Pierre Louis (1787-1872), who bridged adult anatomic pathology and clinical care. Influenced by Morgagni and the tradition pioneered by these Parisian clinicians, Charles-Michel Billard (1800-1832) established the scientific foundation of infant and childhood diseases during his short life. Unfortunately he has been all but forgotten. His extensive 626-page 1828 volume, Traité des Maladies des Enfants Nouveau-Nés et à la Mamelle [Treatise on Diseases of Newborn and Suckling Infants] correlated clinical findings to pathologic autopsy features (Fig. 2). Unlike previous works it was organized by organ system and marked the beginning of scientific pediatrics.

Biography

|

| Fig. 2 Title page of 1833 2nd Edition of Billard’s landmark work. Property of Dr. Shulman (left) Title page of 1839 English translation of 3rd French Edition, of Billard’s Traité (Right) |

C-M Billard was born into poverty in 1800 near Angers (Loire), France, and was orphaned in early childhood. Fortunately, an unmarried aunt assumed his care and arranged for education. Billard was an exceptional student in school and in the College of Angers. From 1819-1824 he studied at the Secondary Medical School of Angers. Secondary medical schools were established throughout France with national funding and curriculum guidance to insure education of qualified medical providers in all French regions. Billard was outstanding, particularly interested in normal and pathologic anatomy, assisting in autopsies, and mastering several languages. During medical school Michel Chevreul, the head of the school, selected Billard to update his obstetrics textbook. In 1824, Billard won first place in a national essay competition, describing normal and abnormal gastrointestinal mucosa resulting in a 585-page 1825 monograph. The monetary prize of the competition enabled Billard to pursue academic training in Paris.

In the early nineteenth century, Paris was the world center of academic medicine. Gross pathologic anatomy was being correlated with clinical observations by several outstanding individuals in the history of medicine, including René Laennac (inventor of the stethoscope), F.X Bichat, Jean Corvisart, Pierre Louis, and Pierre-Auguste Béclard. Within months after arriving in Paris in November 1824, Billard achieved the highest score in the exam for Paris hospital externships. He thus qualified for a highly competitive externship with Pierre-Auguste Béclard (1785-1825), like Billard also an impoverished child of Angers, who died suddenly of erysipelas in March 1825. Later in 1825 Billard advanced from extern to élève intern (equivalent to senior fellow), a most prestigious training position in France, supplementing his meager income by translating foreign articles into French.

By scoring highest in the intern exam in the Paris hospitals, Billard in January 1826 became élève intern at the Hȏpital des Enfants-Trouvés [Hospital for Foundling Children], organized around 1630 by Saint Vincent-de-Paul and more formally established in 1670 by royal edict. There Billard worked under Dr. J.F Baron (1782-1849), who emphasized autopsies to his trainees. The hospital’s massive caseload of abandoned and orphaned infants and children with high mortality gave great opportunity for many autopsies, without parental permission. Billard indicated 5,292 infants were received during 1826; at least 1,404 died.

Billard was inspired by Giovanni Battista Morgagni (1682-1771) of Padua, “How vast and new is the space that is still open before us for the study of diseases of young children,”4 and recorded his debt to him:

“This distinguished observer having enumerated the affections to which newborn children are liable, complains of the little progress that has been made to their pathology, and laments with much feeling that mothers, from a false tenderness, constantly oppose the examinations of the bodies of their children, the symptoms of whose diseases may have been watched with great carefulness and attention.”

Billard then referred to his own Morgagni-inspired efforts:

“I observed with close attention the children in the institution and upon occurrence of a fatal termination of their diseases, I availed myself of the opportunity thus afforded to examine by dissection all their organs, and ascertain the causes and seat of each disease. In this manner has the wish of Morgagni been fulfilled. I have been able by these means to compare the symptoms observed during life with the anatomical lesions by which they have been produced.”1 recorded by Levinson5

“I have written this book with the independence of one who would not draw from existing doctrines anything, however positive, the truth of which could not be proved by established facts or by natural analogy. In this I have but imitated the great number of those who have cultivated science at the present day.”6

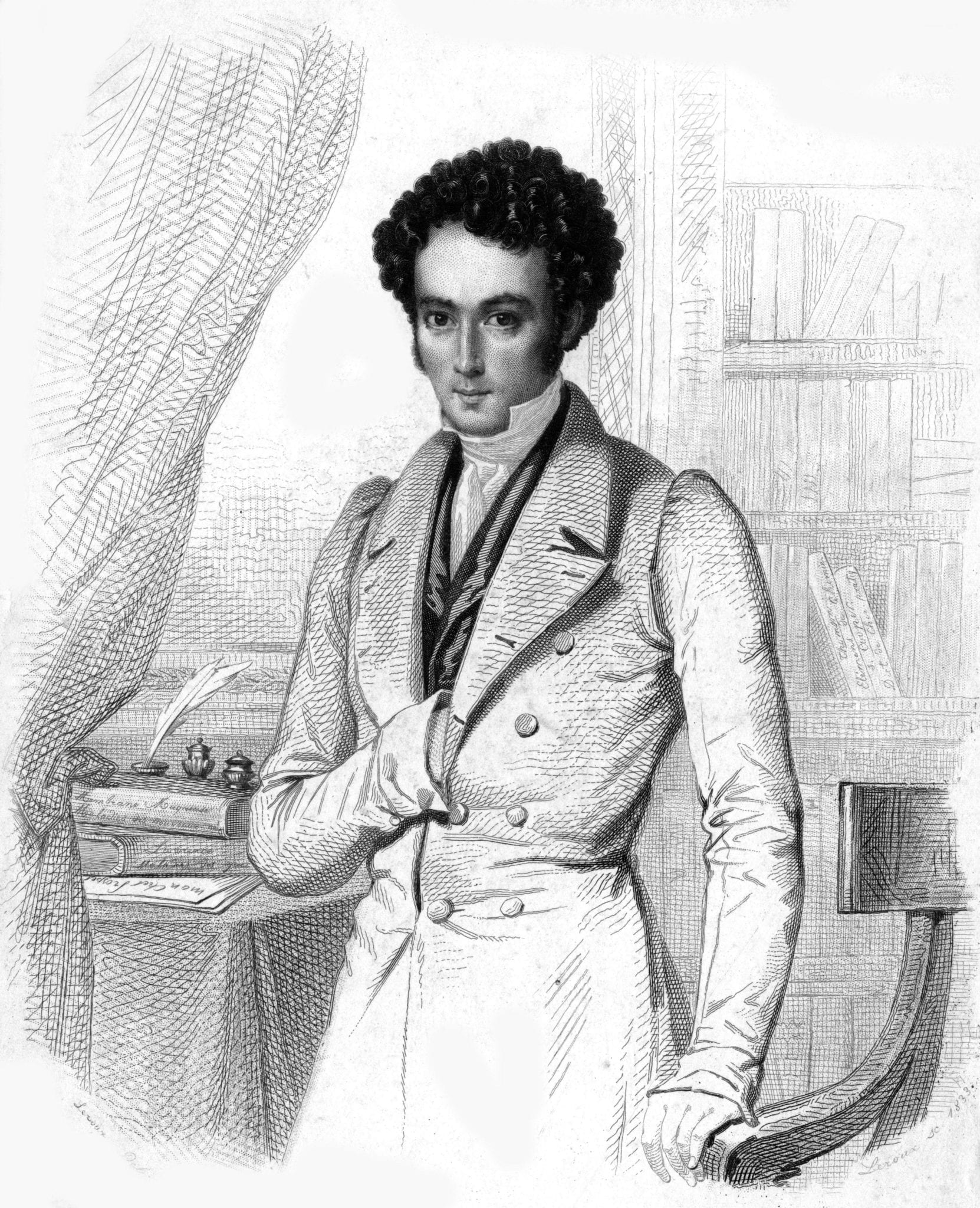

Following the completion of his Paris training, receiving his Docteur en Médecine from Faculté de Paris, and finalizing his major publications including his doctoral dissertation and his Traité, Billard returned to Angers in March 1828 after visiting clinics in Switzerland, Savoy, and Lyons, and opened a general medical practice, foregoing an academic career. He continued to write papers and published many translations of foreign medical literature for compensation. He advocated for the disadvantaged, was a founding member of a commission to abolish poverty in Angers, and participated in many civic organizations. Tragically, Billard died January 31, 1832, at thirty-one, leaving his widow and young son. Tuberculosis, apparently not symptomatic until shortly before his death, was the cause of death (Fig. 3).

Works

|

|

Fig. 3 Portrait of C-M Billard, artist unknown |

Billard’s major works are his 1828 Traité, the Treatise on the Diseases of Newborn and Suckling Infants,1 translated into German, Italian, and English,2 with an Atlas of Pathologic Anatomy including ten hand-colored lithographs by Billard.6 He was very prolific, translating numerous foreign articles into French, publishing a two-volume French translation of Thomson’s Elements of Chemistry and second edition of Chevreul’s text on obstetrics, with two original papers in the Archives Générales de Medecine in 1826, his 585-page tome on the structure of the gastrointestinal mucosa in 1825, a medicolegal essay on viability of newborns in 1828, three additional papers in the Archives in 1827, and a study of edema and sclerema neonatorum.3

The most important Billard work clearly was the Traité, the first pediatric work to classify diseases based upon pathology and utilizing an organ-specific organization.7 After discussing neonatal skin coloration, length and weight, facial expression, cry, and pulse, he classified diseases into categories, such as skin (including exanthems, leprosy, and anthrax), digestive organs, abdominal viscera, airways, circulation, cerebrospinal system, locomotion, reproductive organs, lymphatics, eyes, jaundice, blood abnormalities, and congenital abnormalities.8 He provided detailed analysis of eighty-six autopsied cases covering a wide array of congenital and acquired conditions.

Among the many now familiar disorders included is the first description of neonatal gangrenous enterocolitis (today’s necrotizing enterocolitis), and description of kernicterus in four infants:

“The brain, which was of moderate firmness, presented a uniform and bright yellow in two…while the color was in isolated patches in the other two…In the two subjects where the yellow color of the brain was uniform, there existed at the same time, a general jaundiced affection of the skin.”

Regarding the skin color of very young neonates, Billard wrote:

“It will often be observed, after the red color has disappeared, and before it becomes altogether white, that the skin will exhibit a universal tint of yellow, and sometimes a copper color. This is thought, by physicians generally to indicate an affection by the liver.”9

Billard is also credited with determining the precise age of ductus arteriosus closure,10 and an infant he described with colonic hypertrophy likely had Hirschsprung’s disease.11

Describing congenital urethral atresia, he observed that “obliteration of the urethra caused dropsy of the bladder, and the latter, the hydropic affection of the kidneys, the normal development of which was hindered or even suspended.”9 Billard made important observations on cerebral congestion: “The length of the labor, the necessary tractions in certain maneuvers, the difficulty with which respiration is established, the changes which the circulation undergoes, explain how this apparatus is often the seat of sanguineous congestions, varying from simple injection of the meninges to true apoplexy.”5

He also recognized fetal studies, writing, “During intrauterine life man often suffers many affectations, the fatal consequences of which are brought with him into the world…children may be born healthy, sick, convalescent, or entirely recovered from former diseases.” 9

A second edition was published posthumously in 1833 and a third edition in 1837 by Billard’s close friend Charles Prosper Ollivier (1796-1845), also of Angers. Translations included German (1829), Italian (1830), and the third French edition translated into English by James Stewart of New York (1839). Certainly the importance of Billard’s observations was widely recognized.

Legacy

Clearly Charles-Michel Billard changed the trajectory of pediatrics by establishing an objective scientific basis for ailments of neonates and young children, recognized throughout Europe and North America. However, largely because he died so early in his career, he has been largely forgotten. In the major history of medicine texts he has been omitted or given only passing mention. Beckwith noted that, even in France, C-M Billard is not among the ten Billards included in the massive Dictionnaire du Biographic Francaise.3

Modern pediatrics and pediatric pathology are greatly indebted to Billard’s monumental efforts and observations, and he should be included in the pantheon of pediatrics. As Beckwith noted:

“Billard was neither scholarly drudge nor pedant. From his student days until the end, he had a conspicuously independent intellect, never hesitating to disagree with established authority, but doing so with respectful and dispassionate objectivity…examples where he questions, with neither rancor nor sarcasm, the statements of authorities both living and dead, giving cogent and compelling reasons for his views.”3

References

- Billard C-M. Traité des Maladies des Enfans Nouveau-Nés et a la Mamelle: Paris: J-B Baillière, 1828.

- Billard C-M. A Treatise on the Diseases of Infants: Translated from the Third French edition with an Appendix, by J. Stewart. 1839, Adlard, New York.

- Beckwith, JB. Charles-Michel Billard (1800-1832): Pioneer of Infant Pathology. Pediatric and Devel: Pathology, 2002; 5: 248-56.

- Morgagni, GB. The Seats and Causes of Diseases Investigated by Anatomy: Translated from the Latin edition of 1761 by B. Alexander, London, 1769.

- Levinson A. Progress in Pediatrics: Charles-Michel Billard. Amer J Dis Childhood 1931; 42: 1424.

- Billard C-M. Atlas d’Anatomie Pathologique pour Servir a l’Histoire des Maladies des Enfans: Paris J-B Bailliere, 1828.

- Abt IA. The Influence of Pathology on the Development of Pediatrics: Amer J Dis Child 1927; 34: 1-22.

- Abt-Garrison. History of Pediatrics: The Nineteenth Century. Saunders, Philadelphia, 1965 p.87.

- Dunn PM. Charles-Michel Billard (1800-1832): Pioneer of Neonatal Medicine: Arch.Dis.Child. 1990; 65:711-712.

- Obladen M. History of the Ductus Arteriosus: Neonatology 2011; 99:163-9.

- Ruhräh J. Charles-Michel Billard 1800-1832: A Note on the History of Hypertrophy of the Colon: Amer J Dis Child 1935; 49: 736-8.

STANFORD T. SHULMAN, MD, is Virginia Rogers Professor of Pediatric Infectious Disease at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine and Division Head Emeritus at Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital in Chicago. He has published extensively on Kawasaki Disease, streptococcal infections, and the history of medicine. Dr. Shulman is past president of Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society, past chair of the Section on Infectious Disease of the American Academy of Pediatrics, past chair of the American Heart Association Committee on Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease. He has received several awards from medical societies and has held a number of editorial positions.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 12, Issue 1 – Winter 2020

Summer 2019 | Sections | Physicians of Note

Leave a Reply