Sally Metzler

Chicago, Illinois, United States

In his first published novel from 1742, Henry Fielding chronicles the journey and foibles of three principle characters: the amenable Parson Adams, the so-called beautiful wench Fanny, and her paramour Joseph Andrews—the namesake of the novel.1 Adventures and misadventures befall the young protagonist Andrews, none the least falling in love unknowingly with his sister Fanny and nearly committing incest. Other characters slip in and out of the story, some equally colorful as the primary ones, such as Mrs. Booby, an aristocratic woman consumed with revenge after Andrews spurns her romantic advances.

Fielding’s novel narrates the perils of road travel in mid-eighteenth-century England. The risk of bandits and illness loomed. Our young Joseph Andrews encountered both, and his care and recovery as described proffers the reader an overview of the abilities and perceptions of the medical profession ca. 1742. Two thieves rob Andrews, add injury to insult by beating him, stripping him naked, and leave him lying by a ditch. By the grace of God a stage coach passes by, however the riders are understandably reluctant to allow the bloody and naked Andrews entry into their coach. He lands at the Dragon Inn, under the care of the innkeeper Mrs. Tow-wouse, along with an arrogant surgeon and a gentleman. An entertaining discourse ensues between the gentleman and the surgeon over the importance of Galen and Hippocrates, during which the surgeon challenges the medical knowledge of the gentleman who has yet to read these two famous authors. The surgeon maintains he “seldom goes without them both in my pocket,” to which the gentlemen amusingly replies, “They are pretty large books,” and the surgeon fires back, “I believe I know how large they are better than you.”2

After being beaten on the head, the outlook for Joseph Andrews, according to the surgeon, becomes dim: “his case is that of a dead man . . . contusion on his head has perforated the internal membrane of the occiput, and divellicated that radical small minute invisible nerve which coheres to the pericranium . . .”3 Appearing to be knowledgeable, the surgeon spouts a good dose of nonsensical language, and the result is more pomposity than erudition.

This jargon-heavy diagnosis is replete with nonsense words that are also found in Fielding’s later novel Tom Jones. (See Editor’s note below). Fielding favors “devellicated” as example, a word unknown to both medicine and the English dictionary.

In the end, through a long series of amusing turns and twists of fate, Joseph Andrews, now fully recovered, learns his dear beloved Fanny, the woman to whom he was eternally devoted, was actually not his sister. The two married, and their happiness was “. . . a perpetual fountain of pleasure . . .”4

End Notes

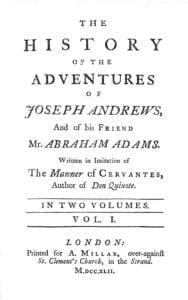

- Joseph Andrews, 1742, is markedly reminiscent of Don Quixote, which Fielding indeed read at university, and dedicated his novel appropriately on the title page: “Written in imitation of the manner of Cervantes, author of Don Quixote. “ All references in this article refer to the following edition: Modern Library College Editions, New York, 1950.

- Henry Fielding, Joseph Andrews, p. 59.

- Fielding, p. 60.

- Fielding, p. 432.

Editor’s note

A similar misfortune befalls Tom Jones, who is hit on the head with a bottle and lies bleeding on the floor to the great consternation of the company at the inn. Almost unanimously they decide that venesection or bleeding is the appropriate treatment, but no one is there to carry out the procedure and the barber is nowhere to be found. Only the innkeeper’s wife displays some common sense. She cuts off some of her hair and applies it to the wound to stop the bleeding. Rejecting with great contempt her husband’s prescription of beer, she fetches a bottle of brandy and prevails on Jones, who has just returned to his senses, to “drink a very large and plentiful draught.”

At last the surgeon appears. He blames everything that was done on others, complains he was not called earlier, and orders the patient to bed. He is very learned, uses much Latin, and explains that symptoms are not always regular but may change from unfavorable in the morning to favorable at noon and again to unfavorable in the evening. He would rather see a skull broken in many pieces then a contusion and lacerated brain, and tells the uncomprehending audience how once he had a patient with a fractured tibia whose broken bones were sticking out through the “vulnus” or wound, the interior membranes “divellicated,” a sanguinary discharge and the appearance of febrile symptoms with an exuberant pulse indicating the need for immediate phlebotomy. Apprehending an immediate “mortification,” he made a large “orifice” in the vein of the left arm and withdrew twenty ounces of blood, which to his surprise were not extremely “sizy and glutinous or indeed coagulated as in pleuritic complaints but rosy and florid, differing little from the blood of those in perfect health.” But all went well after he “applied a fomentation to the affected part, which highly answered the intention” and began to discharge what surgeons in those days called “laudable pus.” He then took his leave, spouting more nonsense, and saying again that he wished he had been called earlier.

SALLY METZLER, PhD, is the director of the art collection at the Union League Club in Chicago.

Leave a Reply