Dustin Grinnell

Boston, Massachusetts, United States

|

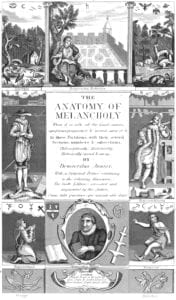

| Frontispiece to the 6th edition of Anatomy of Melancholy by Robert Burton (published under the pseudonym Democritus Junior). 1868. From the Internet Archive and the Public Domain Review. |

The placebo effect

When first exploring literature’s psychological effects on the reader, it is important to consider whether a book can have healing properties by acting as a placebo.

In Persuasion and Healing, Jerome Frank discusses the importance of the connection between patient and healer. In his chapter on the placebo effect, he writes: “I maintain that the success of all techniques depends on the patient’s sense of allegiance with an actual or symbolic healer.”

Why could a book not serve the same role as a doctor or shaman? Instead of the patient-doctor relationship, perhaps there is a reader-book relationship. If you think a novel has therapeutic potential, it just might help your ailment. However, this is only an admission that the healing properties of a piece of fiction might not be intrinsic; perhaps instead, as you think, so shall you be.

The subtle instruction of literature

The healing effects of fictional narratives seem most potent when they do not blatantly aim to uplift the reader. “As Aristotle observed, the deepest audience pleasure is learning without being taught,” write Robert McKee and Thomas Gerace in Storynomics. “When a tale dramatizes its meaning skillfully, the audience feels no mental strain and yet comes away with a fuller understanding of the workings of the world and the human heart.”

Consider for example fables and fairy tales, like those compiled by the Brothers Grimm, or the genre of inspirational literature such as Wisdom of the Peaceful Warrior by Dan Millman or The Five People You Meet in Heaven by Mitch Albom. These are designed to directly console the reader, delivering instruction, wisdom, and spiritual knowledge through overt dialogue, plot devices, and character development. They risk coming off as a lecture or preachy, which many readers may find off-putting. In fact, Frye’s mother may have made her miraculous recovery precisely because the books she read were not specifically designed to heal.

In a similar vein, there are countless nonfiction books that aim to alleviate suffering in people with almost any mental health problem—for example, Overcoming Anxiety for the anxious and Beat Depression and Reclaim Your Life for the depressed. Prescriptive nonfiction written for such mental disorders is more direct and less open to interpretation than the narratives this essay is exploring. Fictional narratives allow readers to discover lessons on their own.

That is not to say that pieces of literature, or “artistic works,” do not express moral ideas. However, unlike nonfiction, fictional texts approach truths indirectly, nonexplicitly, and unobjectively. Literature does not just distract us from our lives; in some ways, it helps us learn how to live, without being as direct as nonfiction or as sanctimonious as inspirational writing.

A writer of literary self-help and founder of The School of Life, Alain de Botton, wrote that Leo Tolstoy did not believe in the idea of art for art’s sake. He was deeply invested in the belief that good art should make us less moralistic and judgmental and should supplement religion by developing our reserves of kindness and morality.

In his paper “Dream Some More: Storytelling as Therapy,” Carl Lindahl agrees that fiction is more convincing than nonfiction. “Researchers have repeatedly found that reader attitudes shift to become more congruent with the ideas expressed in a [fictional] narrative.”

Other research now shows that stories are more likely to leave an impression than information (i.e., facts and data). In traditional communities, stories are a kind of information—and the primary tools for teaching, converting memories, and sharing values. Jonathan Gottschall writes in The Storytelling Animal that “fiction seems to be more effective at changing beliefs than nonfiction, which is designed to persuade through argument and evidence.”

Identification, catharsis, and integration

In “Bibliotherapy for Hospital Patients,” Paula McMillen and Dale-Elizabeth Pehrsson discuss the use of bibliotherapy for hospital patients. Books helped address the emotional needs of patients who were dealing with fears, confusion, embarrassment, sense of lost control, and increased vulnerability.

The authors present a psychodynamic model by which literature achieves its therapeutic effect. “Readers are encouraged to identify with significant characters in the story . . . to experience emotional catharsis as the story characters express themselves . . . and then to gain some insight into themselves and their situations.”

McMillen and Pehrsson cite a study by Laura J. Cohen, who has written extensively on the therapeutic mechanisms by which literature works. In the study, readers were going through difficult periods of their lives. Regardless of the literary genre, Cohen found that “identification with the characters and/or situations in the selected literature was acknowledged by virtually all readers as the key to experiencing positive effects.”

This identification between a patient and a character’s situation is essential to the patient deriving the maximal benefit, according to McMillen and Pehrsson. As you read and see yourself in fictional characters, emotions may arise, particularly negative ones. A real benefit “of reading can be seeing how others have dealt with problems or survived difficult situations,” according to the authors.

The promotion of empathy through identification with characters

In “A Feeling for Fiction,” Keith Oatley writes that reading a book is a passive experience only in the physical sense. Emotionally, it is quite an active experience. As we read, “we join ourselves to a character’s trajectory through the story world. We see things from their point of view—feel scared when they are threatened, wounded when they are hurt, pleased when they succeed.”

Oatley argues that we enjoy feeling with other people, even when sometimes the feelings are negative. In the novel Ordinary People by Judith Guest, the pain of the protagonist, Conrad Jarrett, is our pain. The novel tragically illustrates that sometimes bad things happen to good people. The Jarretts are a nuclear family, with a loving husband and wife and two boys of whom any parent would be proud. But tragedy strikes. The elder son, Buck, dies in a boating accident, and the younger, Conrad, survives. Blaming himself, Conrad attempts suicide and spends four months in the psychiatric ward of a hospital. That is where Ordinary People begins.

When we first meet Conrad, he is anxious, struggling, living from day to day. His father, Calvin, is a sweet man who wants to make sure Conrad is safe and happy. But Conrad’s mother, Beth, is in denial and acts as if nothing has happened, distracting herself with golf and discussing travel plans as if the family had not been ripped apart. Beth does not see the value in acknowledging the trauma; she just wants to move on and refuses talk about her son Buck—her favorite son. She buried her love with Buck and cannot show Conrad affection.

Conrad finds the courage to call a psychiatrist, Dr. Berger. Judith Guest spends a great deal of the novel depicting a realistic process of psychotherapy and how it works on a struggling patient. As readers, we relish Conrad’s courage to engage with his feelings in therapy.

When we read Ordinary People, we step into Conrad’s shoes and have the luxury of watching him navigate an experience that, in all likelihood, we have not experienced ourselves. While we might not have struggled with suicidal depression or lost a family member in an accident, we can still gain insights into ourselves as we follow Conrad’s path toward healing. In Middlemarch, George Eliot called this “the extension of our sympathies” because literature amplifies experience and extends our contact with people beyond ourselves.

The important aspect of this identification with Conrad is that we have distance. We are an “impartial spectator,” as Adam Smith wrote in The Theory of Moral Sentiments. In Ordinary People, Conrad elicits our sympathy, but since he is fictional, we can stay impartial and gain insight without having the natural reactions that may occur in real life. For example, if Beth were our own mother, we might not be able to gain insight into our problems—or her suffering, for that matter—because we would be too angry with how she was treating us. We would not be able to maintain objectivity.

Fictional narratives are simulations that allow impartial readers to play out imaginary situations with characters who do and say imaginary things. As we read, we ask, “If I were there, in that moment, with those people, what would I do or say or believe? How might I handle the loss of a sibling? What if I lost a child? Would I have the courage to seek help?” Thus literature gives us practice for different situations and imagined scenarios expand our own range of possibilities.

Unlike watching a play or a movie, reading fictional prose allows the reader direct access to the interior thoughts of characters. The author can clearly state what the character is thinking or feeling. By experiencing what a character thinks and feels, we “become sensate,” writes Lisa Cron in Wired for Story. More importantly, we can understand what these thoughts and feelings mean to the character whose mind we are temporarily inhabiting.

“That’s what readers came for,” writes Cron. “Their unspoken hardwired question is, if something like this happened to me, what would it feel like? How should I best react? Your protagonist might even be showing them how not to react, which is a pretty handy answer as well.”

After spending time in a fictional character’s mind, we return to our lives with references to help us better understand the people around us—their choices, their behavior, their beliefs. And when they misstep—“to err is human” —perhaps we can see things from their point of view —“to forgive is divine.” By witnessing the missteps of these imagined characters, perhaps we can avoid the missteps in our own lives. In Persuasion and Healing, Frank writes that “new experiences provided by therapy can enhance morale by showing patients potentially helpful alternative ways of looking at themselves and their problems.”

We might also show compassion. We might ask not “What’s wrong with you?” but “What happened to you?” In How Should We Live?: Great Ideas from the Past for Everyday Life, Roman Krznaric writes about George Orwell’s radical experiments to cultivate empathy. He would dress as a tramp and spend a long time at hostels for the homeless. Krznaric calls this a form of experiential empathy. Orwell’s empathy grew for a class of citizens that differed from his privileged upper-middle-class origins.

In his chapter on empathy, Krznaric writes, “Empathy matters not just because it makes you good, but because it is good for you. It has the power to heal broken relationships, erode our prejudices, expand our curiosity about strangers, and make us rethink our ambitions. Ultimately, empathy creates the human bonds that make life worth living.”

Catharsis: feeling badly without consequence

Two thousand years ago, Aristotle wrote in Poetics that while history lets us know what has happened, fiction is more important because it considers what can happen. Readers can go to literature to identify with characters, to self-reflect, and to gain insight into themselves without risking harm to themselves or other consequences.

In Literature as Therapy, Northrop Frye reminds us that Aristotle defined tragedy as a form that evokes emotions of pity and fear to affect a catharsis of those emotions. Frye says that literature presents readers with obstacles that elicit a catharsis (from katharos, clearing obstacles) that we might not have thought we needed.

While reading Ordinary People, we pity Conrad because he lost his brother and attempted suicide. Conrad is suffocated by grief and guilt and is desperately trying to maintain control. We are also afraid of Beth because she cannot show affection toward Conrad and ignores her eldest son’s passing by golfing and socializing. In short, we have sympathy for Conrad and are repulsed by Beth.

“If these emotions of pity and terror are purged through catharsis, as they are in tragedy,” writes Frye, “then the response is a response of emotional balance, a kind of self-integrating process. That is, what we feel when we respond to a tragic action is, well, yes, this kind of thing does happen: it inevitably happens given these circumstances.”

In Ordinary People, Conrad, our tragic hero, takes what Frye refers to as excessive action—or what Aristotle calls hybris—which inevitably leads to a restoring of balance in the natural order—or nemesis, according to Aristotle. For Conrad, that action is working out his troubles with his therapist. As the story progresses, the reader sees Conrad heal and senses the coming of a breakthrough, which Guest delivers in a climactic scene between Conrad and his therapist, Dr. Berger.

Northrop Frye suggests that the purpose of tragedy is to allow us to injure ourselves before life does. Tragedy allows readers to play inside a “counter environment,” where we can purge feelings of pity and terror that we would not be able to bear in real life.

In The Dynamics of Literary Response, Norman Holland writes that literature allows readers to experience intense emotions, especially emotions we ordinarily repress. Experiencing these “intense emotive dramas” is what he believes to be “a condition for complete and fully realized personhood.”

A coherent narrative

Fiction can also help provide our lives with a coherent story. Such an effect may be especially necessary when someone has experienced a trauma or tragedy that can produce a feeling of disbelief that this has happened. Flora Armetta explains this in “The Therapeutic Novel,” in which she writes: “People who have experienced loss or trauma may find healing if they are able to turn their life stories into a narrative that hangs together and makes sense.”

“Recent research suggests that developing a story from the events in one’s life—not necessarily a story with a happy ending, just a true and ‘coherent’ story, as opposed to a ‘fragmented’ one—can bring real relief from depression and anxiety.” And that is what literature provides, in Armetta’s view. “Consider the vast body of great writing that is precisely about the process that psychotherapy evidently provides: the attempt to narrate a life story as a means of understanding it.”

A different point of view

Normally, other people’s minds are inaccessible. We might have a good idea what someone is thinking or feeling, but unless they tell us, we are only guessing. The ability to intuit the thoughts, feelings, intentions, and beliefs of another person is known as “theory of mind,” and research shows that reading literary fiction sharpens it.

Psychologists at the New School for Social Research found that participants who read passages from literary short stories (as opposed to popular fiction) enhanced their ability to empathize with another person. After reading, each participant took the Reading the Mind in the Eyes Test (RMET), a test that asks participants to look at photos of subjects’ eyes and identify what they are feeling (e.g., annoyed or scared). The participants who read literary fiction were better able to know what another person was thinking or feeling.

Following fictional characters offers a level of access that is hard to achieve with real people in person. In an interview, author David Foster Wallace said he believed that serious fiction gave a reader imaginative access to other skulls. “If a piece of fiction can allow us imaginatively to identify with a character’s pain, we might then also more easily conceive of others identifying with our own. This is nourishing, redemptive; we become less alone inside.”

In this way, engaging in fictional worlds can encourage tolerance. Northrop Frye says that our own beliefs are also just possibilities; exercising our imagination with fiction allows us to see the possibilities in the beliefs of others. “Bigots and fanatics seldom have any use for the arts, because they’re so preoccupied with their beliefs and actions that they cannot see them as also possibilities.”

The words to understand our own feelings

In How Proust Can Change Your Life, Alain De Botton writes that we should read books to learn what we feel. Have you ever read something and thought, “Yes! I always knew that to be true, but I just didn’t have the words for it”? Sometimes an author can express something we have felt but have not been able to clearly articulate.

The words and deeds of fictional characters can give us the vocabulary to know what we are feeling. In Persuasion and Healing, Frank explains that words are the main tool we humans use to analyze and organize our experiences. The goal of all psychotherapies is to increase a patient’s sense of security and mastery by giving names to experiences that seemed haphazard, confusing, or inexplicable.

Consider Beth Jarrett in Ordinary People. A tragedy has befallen her family. Have we not all experienced hard times and just wanted to bury our heads in the sand as Beth does? We might want to return to a time when things were normal, but we cannot. Things will never be the same. By observing Beth, we understand that she is denying reality because it is too painful to embrace the tragedy head-on.

“Once the unconscious or ineffable has been put into words, it loses much of its power to terrify,” writes Frank. “The capacity to use verbal reasoning to explore potential solutions to problems also increases people’s sense of their options and enhances their sense of control.”

This is called the “Rumpelstiltskin principle,” named after the fairy tale in which a queen breaks the power that wicked words have over her by guessing Rumpelstiltskin’s name. In The Mind Game E. Fuller Torrey writes that a psychiatrist listens to a patient and helps him define his own experience. Just the naming is therapeutic, writes Torrey. A patient’s anxiety lessens because a respected and trusted specialist has shown him how to understand the problem. The magic of the right word, so to speak.

Torrey believed that naming something was the first step in gaining control over it. In Ordinary People, we understand that Conrad is anxious. We recognize that Beth is in denial. Guest dramatizes her characters’ problems, giving the reader vocabulary and the means to resolve our own similar states of mind. The author of “Rumpelstiltskin” adds: “The identification of the problem is a signal to the patient that he is not alone with his illness, but that there is someone who understands him. Moreover, the name of the psychological problem promises an opportunity of finding a cure because if it has been named, it has usually been brought under control.”

Fiction can elicit a sense of solidarity by “talking one’s language”

When you experience illness or trauma, it is not unreasonable to expect some level of self-involvement, a fixation on or even obsession with your malady or difficult situation. If you are young or experiencing a troubling event for the first time, you might assume you are the only one to have ever dealt with such a problem.

In such instances, a fictional narrative may have healing properties because it follows characters who have been through what we have been through, seen what we have seen, or felt what we have felt. If a character walks like us and talks like us, he “speaks our language.” More importantly, a character may be suffering from something we have suffered from, and to our surprise they survived. In some cases, a character may be experiencing a more extreme situation than ours, allowing us to see our problems from a new perspective.

In Persuasion and Healing, Frank writes that distress from a crisis or breakdown is made worse by the feeling that no one else has ever been through a similar experience and therefore no one would understand. Engaging with a piece of fiction that contains characters like us can help us realize we are not the only ones who have dealt with what we are dealing with. Lisa Cron calls this “marveling in relieved recognition.”

Bill Wilson and Robert Smith, the cofounders of Alcoholics Anonymous, realized that the best way to remain sober was to engage in a ritualistic exchange of stories about alcoholism. They believed that narratives of addiction allowed members to imaginatively relive dramas from their past, but to do so within a space where there was a strong identification between storyteller and listener. In Reading as Therapy, they write that such sympathetic identification creates a sense of solidarity, “not merely with fictional characters, but also with other actual and potential readers who respond in a similar fashion.”

The therapeutic power of expression

For centuries, the book club has allowed people to read a common book and discuss its ideas. In a group setting, people share what the story means to them and how it, or the characters within it, has informed their lives. In the short story “Grief” by Anton Chekhov, the protagonist, a man who drives a chariot, has lost his son. He tries to broach the subject with his riders, but no one seems interested. At the end of the story, he finally talks to an unlikely audience: his horse.

The reader does not hear what the man says. We just know that he has said something, and we sense he is unburdened—he grieved. Chekhov signals to the reader that we can feel better if we express ourselves, even if just to an animal. The most important component of this lesson is not necessarily that we have talked but that we have been listened to.

In Ordinary People, Conrad’s therapist, Dr. Berger, constantly encourages Conrad to open up and talk in therapy sessions. “Something is bugging you, something is making you nervous. What is it?” More importantly, Dr. Berger encourages Conrad to feel. “Forget how it looks. How does it feel?” He tells him that if he cannot feel pain, he cannot feel joy or goodness or love. “Sealing yourself off is just going through the motions,” says Dr. Berger. And by opening up about his troubles, including his suicide attempt, Conrad recovers.

Guest has produced a thought experiment in how to manage grief. How to explore feelings we may be suppressing. The reader may be encouraged to ask, “What am I not saying?” As such, it encourages us to start a dialogue about things unsaid, especially within ourselves.

Discovery of our shadowy aspects

As previously mentioned, we do not just experience positive emotions while reading. Fiction also allows us to engage with the negative, less pleasant aspects of personhood. In fiction, we can encounter darkness and sometimes entertain taboo, even criminal, thoughts.

In The Accidental Tourist by Anne Tyler, the protagonist’s wife, Sarah, says she has been thinking about visiting their son’s killer in prison. She wishes to tell him that he did not just kill her son, Ethan—he killed her and the protagonist, Macon. She tells Macon that she has fantasized about shooting him. These are dark thoughts. If Sarah wanted to act out her dark thoughts, she probably could, albeit with great consequence to herself.

We too have such choices to act out harmful thoughts. The Danish philosopher Soren Kierkegaard called this the “dizziness of freedom.” For example, the terror we feel at the edge of a cliff is not necessarily the fear that we will fall. Rather, it is that we could throw ourselves off, if we wanted to. We have that choice.

Macon tells Sarah that such thoughts are unproductive. Macon has not grieved the loss of his son; he is unemotional and in denial, much like Beth in Ordinary People. As we read, we understand that Sarah is making idle threats; she is trying to unburden herself. By dramatizing Sarah’s darker thoughts, Tyler validates our own and affirms that it is completely natural—and often quite therapeutic—to talk them out.

In the article “Move Over Freud: Literary Fiction Is the Best Therapy,” Salley Vickers writes that reading about villains allows us to discover shadowy aspects of ourselves that we have failed to acknowledge or recognize. Vickers writes that in the psychological novel Crime and Punishment, “Dostoevsky illuminates, through the example of his character . . . that our civilised selves may conceal a lethal armoury, potentially capable of atrocities.”

In Persuasion and Healing, Frank writes that unpleasant emotions can lead patients to search actively for relief, which is an added benefit of exploring the shadowy aspects of ourselves. “Intense emotional experiences .. . may break up old patterns of personality integration and facilitate the achievement of better ones.”

It is also worth noting that no human is perfect. Most of us feel guilty about something. A bad habit or an uncouth aspect of ourselves, perhaps. As readers, it is hard to relate to a perfect character, which is why fiction writers are taught to give their characters flaws, especially their protagonists. As readers, some natural guilt or self-loathing may subside momentarily when we relate to a character with less-than-admirable qualities. We realize that perhaps the unlikable aspects of ourselves are not major failings after all.

Either way, in witnessing characters presented with “warts and all,” we see that we are not the only ones with such problems. It is when we think we are alone with the unappealing aspects of ourselves that disgust and/or self-chastisement seem most pronounced.

– Read Part III of this three part series here.

References

- Armetta, Flora. “The Therapeutic Novel.” The New Yorker. February 16, 2011. https://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/the-therapeutic-novel.

- Ayto, John. Dictionary of Word Origins: Histories of More than 8,000 English-Language Words. Arcade, 1990.

- Begley, Sarah. “Read a Novel: It’s Just What the Doctor Ordered.” Time. October 27, 2016. http://time.com/4547332/reading-benefits.

- Berg, Sara. “In Battle against Doctor Burnout, Reading—for Fun—Is Fundamental.” American Medical Association. January 18, 2019. https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/physician-health/battle-against-doctor-burnout-reading-fun-fundamental.

- Berger, John, and Jean Mohr. A Fortunate Man: The Story of a Country Doctor. Vintage, 1967.

- Berthoud, Ella, and Susan Elderkin. The Novel Cure: From Abandonment to Zestlessness: 751 Books to Cure What Ails You. Penguin, 2013.

- Bloom, Harold. How to Read and Why. Scribner, 2001.

- Brooks, David. The Road to Character. Random House, 2016.

- Camus, Albert. The Myth of Sisyphus. Hamish Hamilton, 1955.

- Chekhov, Anton. “Misery.” Peterburgskaya Gazeta, no. 26 (April 26, 1886).

- Fadiman, Clifton. How to Use the Power of the Printed Word. Anchor, 1985.

- Cooney, Elizabeth. “The Healing Power of Story.” Harvard Medical School (May 15, 2015). https://hms.harvard.edu/news/healing-power-story.

- Cooper, Jonny. “Meet the Bibliotherapists Who Can Cure Your Children . . . with Books.” The Telegraph. November 1, 2016. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/family/parenting/meet-the-bibliotherapists-who-can-cure-your-children–with-books.

- Cousins, Norman. Anatomy of an Illness as Perceived by the Patient: Reflections on Healing and Regeneration. W. W. Norton & Company, 2005.

- De Botton, Alain. How Proust Can Change Your Life. Vintage, 1998.

- ———. “Leo Tolstoy.” The Book of Life. Accessed [February 14, 2019]. https://www.theschooloflife.com/thebookoflife/leo-tolstoy.

- ———. “Nietzsche On: The Superman” (video). The School of Life, November 9, 2016, 2015. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bxiKqA-u8y4.

- ———. Religion for Atheists: A Non-Believer’s Guide to the Uses of Religion. Vintage, 2013.

- ———. “What is Literature For?” The School of Life, September 18, 2014. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4RCFLobfqcw&feature=youtu.be&list=PLwxNMb28XmpdJpJzF2YRBnfmOva0HE0ZI.

- Dovey, Ceridwen. “Can Reading Make You Happier?” The New Yorker (June 9, 2015). https://www.newyorker.com/culture/cultural-comment/can-reading-make-you-happier.

- Erofeyev, Victor. “The Secrets of Leo Tolstoy.” The New York Times (November 19, 2010). https://www.nytimes.com/2010/11/20/opinion/20iht-ederofeyev.html.

- “Faculty Spotlight: Sneha Mantri, MD.” Duke University School of Medicine. January 28, 2019. https://neurology.duke.edu/about/news/faculty-spotlight-sneha-mantri-md

- Frank, Jerome D. Persuasion and Healing: A Comparative Study of Psychotherapy. Johns Hopkins University Press, 1961.

- Frye, Northrop. “Literature as Therapy.” In The Eternal Act of Creation: Essays, 1979–1990, 21–36. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1992.

- Gaiman, Neil. “Neil Gaiman: Why Our Future Depends on Libraries, Reading and Daydreaming.” The Guardian. October 15, 2013. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2013/oct/15/neil-gaiman-future-libraries-reading-daydreaming.

- Grubin, David, filmmaker. The Buddha. 2013. Television documentary.

- Hesse, Hermann. Siddhartha: A Novel. Bantam, 1981.

- Hughes, Bettany, host. Genius of the Modern World. 2016. Television documentary.

- Kafka, Alexander C. “Why Storytelling Matters in Fields Beyond the Humanities” (An Interview with Rita Charon). The Chronicle of Higher Education. October 4, 2018. https://www.chronicle.com/article/Why-Storytelling-Matters-in/244729.

- Krznaric, Roman. How Should We Live?: Great Ideas from the Past for Everyday Life. 2nd ed. BlueBridge, 2015.

- Lindahl, Carl. Dream Some More: Storytelling as Therapy. Folklore. October 1, 2018.

- Martin, Rachel, host. “To Cure What Ails You, Bibliotherapists Prescribe Literature.” NPR. September 4, 2015. https://www.npr.org/2015/09/04/437597031/to-cure-what-ails-you-bibliotherapists-prescribe-literature.

- McKee, Robert, and Thomas Gerace. Storynomics: Story-Driven Marketing in the Post-Advertising World. Twelve, 2018.

- McMillen, P. S., and D. Pehrsson. “Bibliotherapy for Hospital Patients.” University Libraries (2004). https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/62872843.pdf

- McWilliams, James. “Books Should Send Us into Therapy: On the Paradox of Bibliotherapy.” The Millions. November 2, 2016. https://themillions.com/2016/11/books-should-send-us-into-therapy-on-the-paradox-of-bibliotherapy.html

- Miller, James. Examined Lives: From Socrates to Nietzsche. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2011.

- Nietzsche, Friedrich. Thus Spoke Zarathustra. Dover, 1999.

- Oatley, Keith. “A Feeling for Fiction.” Greater Good Magazine. September 1, 2005. https://greatergood.berkeley.edu/article/item/a_feeling_for_fiction.

- Online Dictionary for Library and Information Science (ODLIS). s.v. “bibliotherapy.” Accessed [date]. https://www.abc-clio.com/ODLIS/odlis_b.aspx#bibliotherapy.

- Proust, Marcel. On Reading. Hesperus Press. August 24, 2011.

- Rosen, Charles. “The Anatomy Lesson”. The New York Review of Books. June 9, 2005. https://www.nybooks.com/articles/2005/06/09/the-anatomy-lesson.

- Schwalbe, Will. Books for Living. Knopf, 2016.

- Tolstoy, Leo. The Death of Ivan Ilyich. Penguin Classics edition. May 27, 2008.

DUSTIN GRINNELL is a writer based in Boston, MA, with interests in storytelling and medicine. His narrative nonfiction and journalism has appeared in The LA Review of Books, The Boston Globe, New Scientist, VICE, Salon, and Writer’s Digest, among others. He is also the author of The Genius Dilemma and Without Limits. He holds a BA in psychobiology from Wheaton College (MA), an MS in physiology from Penn State, and is currently pursuing an MFA in fiction from the Solstice program in Chestnut Hill, MA. He works as a staff writer for a hospital in Boston.

Summer 2019 | Sections | Books & Reviews

Leave a Reply