JMS Pearce

East Yorks, England

|

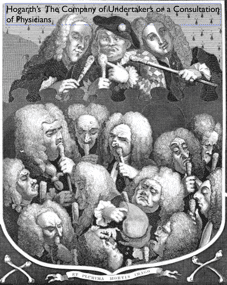

| Fig 1. Hogarth’s The Company of Undertakers or a Consultation of Physicians |

Over many centuries there have been several icons symbolic of medical practice. Typical is the single serpent, the Aesculapian wand — a “totem of Medicine”— seen in the constellation Ophiochus (the serpent holder). Serpents in ancient cultures represented fertility, rebirth, and strength. The Aesculapian wand is often confused with the two serpents that formed the Caduceus of Hermes. However, Hermes was patron of messengers, thieves, and merchants; he was neither healer nor guardian of physicians.

From the seventeenth to the nineteenth centuries the cane became the physician’s unfading hallmark. Canes date back to Homeric times, and their purpose was similar to the sinister-looking beaks of the masks worn by plague doctors. It was thought that contagion was spread by putrid air, so the beaks of masks and the hollowed handles of canes were filled with aromatic herbs, lavender, or myrrh to protect physicians from foul smells and noxious air. This was illustrated in Hogarth’s The Company of Undertakers or a Consultation of Physicians, 1736, which showed physicians smelling aromatics in such canes. (Fig 1.) They became lavishly ornate with hollow, perforated heads made from ivory, gold, or silver.

William Macmichael’s The Gold-Headed Cane,1 (Fig 2.) originally published in 1827, is the imaginative “autobiography” of one particular gold-headed cane owned by five eminent physicians; several held high office in the Royal College of Physicians. Initially reviews criticized the book because it concentrated disproportionately on illnesses of the royalty and aristocracy, “though at the time, there was intense interest in Royal illnesses and death-beds.”5 Macmichael’s book became highly regarded, not least by both Osler and Cushing. It is “a book that all medical historians and scholarly physicians will treasure.”2

The Gold-Headed Cane

Its stories begin:

When I was deposited in a corner closet of the Library, on the 24th of June, 1825, the day before the opening of the new College of Physicians, with the observation that I was no longer to be carried about, but to be kept amongst the reliques of that learned body, it was impossible to avoid secretly lamenting the obscurity which was henceforth to be my lot.… I had, however, been closely connected with medicine for a century and a half; and might consequently, without vanity, look upon myself as the depositary of many important secrets, in ‘which the dignity of the profession was nearly concerned. I resolved, therefore, to employ my leisure in recording the most striking scenes I had witnessed.1

It tells of the adventures of the famous cane, successively in the possession of Radcliffe, Mead, Askew, William and David Pitcairn, and Matthew Baillie. Then in 1824 it was retired to a glass case in the library of the Royal College of Physicians.3 In Macmichael’s quirky book the cane itself relates a series of biographies and consultations of these and other famous physicians of the day.1 But rather than describing generally the physicians and practices of that time, it portrays the vagaries of the medical encounters with royalty and the aristocracy in eighteenth century England.

|

| Fig 2. Macmichael’s The Gold Headed Cane 1827 |

Macmichael adopted an unusual, somewhat difficult device, by making an inanimate cane do all the talking. It successfully allowed the cane to embellish events “in a way that would otherwise be laborious, and to describe them lightly as a story, without demanding the accuracy and detail needed for an historical record.”5 The book was luxuriantly interleaved with portraits and Hogarth’s picture, Consultation of Physicians.

The second edition appeared in 1828 and a third, edited by Munk in 1884. George Peachey reissued it in 1923.4 A facsimile edition of the author’s original annotated copy was published in 1968 for the 450th anniversary of the Royal College of Physicians, with a biographical introduction by Thomas Hunt (1901-1980), vice president, and great-grandson of Macmichael.5 Sir Max Rosenheim says in his preface:

“The Gold-Headed Cane” is so closely associated with our College and the purpose for which it stands that I am especially pleased that Dr Macmichael’s great grandson – now Vice President of the College – should be reproducing his copy of the author’s original annotated volume on this special occasion of our Anniversary.

The Cane’s physicians

The cane was made for John Radcliffe (1650-1714), born in Wakefield, and physician to King William III. His cane had no hole but a crutched handle, and was engraved with his arms; subsequently the other physicians had their arms engraved upon it.5 Both eccentric and eminent, Radcliffe was at times eristic, overbearing, and “often in a cholerick temper.” But “his general good sense and practical knowledge of the world distinguished him from all his competitors.” He was much in demand.6 He was known for his remark that as a young practitioner he possessed twenty remedies for every disease, but at the close of his career he found twenty disease for which he had not one remedy.

A wealthy man, at his death he left considerable sums to Oxford University, resulting in the Radcliffe Infirmary, Observatory, and Library.

The cane extols the virtues of the much gentler Richard Mead (1673-1754), who succeeded to Radcliffe’s practice and was both a distinguished physician and philanthropist:

one who excelled all our chief nobility in the encouragement he afforded to the fine arts, polite learning, and the knowledge of antiquity.

Mead studied classics and philosophy, and trained at Padua and with Boerhaave. A scholarly man, Mead was an avid collector and bibliophile. He was involved with Foundling Hospital, established by Thomas Coram in 1741. At Newgate Prison he investigated “the new Method of Smallpox Inoculation” in 1721 by introducing into the nostrils a tent, wetted with matter taken out of ripe smallpox pustules; this was superseded by Jenner’s vaccination with cowpox in 1798. Mead published books on smallpox, plague, and measles. He gave the Harveian Oration of the Royal College of Physicians in 1723, and attended the illnesses of Isaac Newton, George I and George II, and Queen Anne. He lived “more in the broad sunshine of life than any other man,” according to Samuel Johnson. A monument in his honor stands in Westminster Abbey.

Anthony Askew (1722-1774) studied in Cambridge, Leyden, and Paris, and practiced in London, strongly supported by Richard Mead. The cane says little about him. His chapter is mostly centered on his friend, the famous William Heberden. Askew too was a classicist and bibliophile. He gave the Harveian Oration and was active in the Royal Society and the Royal College of Physicians.

From Askew the cane passed to William Pitcairn (1711-1791), who studied under Boerhaave and graduated in medicine at Rheims and Oxford. He was an accomplished botanist and physician to St. Bartholomew’s Hospital for thirty years, and president of the college for ten years. The cane relates:

For several years Dr. Pitcairn was the leading practitioner in the City, and thus afforded me an opportunity of observing more closely the manners of the wealthy inhabitants of that quarter, and contrasting them with the habits of the more polite and courtly end of the town, to which I had previously been chiefly accustomed. In 1784 he resigned the office of President, being succeeded by Sir George Baker;

|

| Fig 3. William Macmichael. From Wellcome images |

From William Pitcairn the cane passed to his nephew David Pitcairn (1749-1809), and informs us:

[he] resided many years in Lincoln’s Inn Fields, and was early admitted a Fellow of the Royal and Antiquarian Societies. To these meetings it was my lot often to be taken…

no one was so frequently requested by his brethren to afford his aid in cases of difficulty. He was perfectly candid in his opinions… The extensive practice of my master necessarily brought me in contact with every physician of any eminence, of whom the most prominent was unques- tionably that profound and elegant scholar, Sir George Baker… To return to Dr. David Pitcairn his manner was simple, gentle, and dignified; from his kindness of heart he was frequently led to give more attention to his patients than could well be demanded from a physician;

He was the first to connect valvular heart disease to rheumatic fever.

From David Pitcairn the cane passed to Matthew Baillie (1761-1823), nephew of William and John Hunter. But the cane then felt somewhat neglected:

When I passed from the bands of Pitcairn into the possession of Dr. Baillie, I ceased to be considered any longer as a necessary appendage of the profession, and consequently the opportunities I enjoyed of Baillie seeing the world, or even of knowing much about the state of physic, were very greatly abridged… The attention which he [Baillie] had paid to morbid anatomy (that alteration of structure which parts have undergone by disease), enabled him to make a nice discrimination in symptoms, and to distinguish between disorders which resemble each other. It gave him a, confidence also in propounding his opinions, which our conjectural art does not readily admit; and the reputation which he enjoyed universally for openness and sincerity, made his dicta be received with a ready and unresisting faith.

In 1795 Baillie published his famous and probably the first English work on morbid anatomy. In 1799 he worked as a physician at St. George’s Hospital and established a hugely popular private practice. He gave the Croonian Lecture in 1791. Twenty years later he became physician-extraordinary to George III. During the King’s madness Baillie visited him hundreds of times at Windsor.

The Cane

The origins of this cane are uncertain, for it tells us:

Of my early state and separate condition I have no recollection whatever; and it may reasonably enough be supposed, that it was not till after the acquisition of my head that I became conscious of existence, and capable of observation.

The cane, however, recollects clearly the first consultation at which it was present, at Kensington Palace where Dr. Radcliffe was called to attend His Majesty William the Third.

A cane was regarded as an essential part of the equipment of every physician. Munk’s third edition of The Gold-Headed Cane explains the origin of the custom. The cane, usually carried by physicians, had for its head a knob of gold, silver, or ivory, which was hollow, “a vinaigrette, which the doctor held to his nose when he went into the sick room so that its fumes might protect him from contagion and other noxious exhalations from his patient.” The favorite preparation for this purpose was the “vinegar of the four thieves,” or Marseilles Vinegar which, according to the confession of four thieves who had robbed plague stricken people in Marseilles, had prevented them from contracting the disease while pursuing their nefarious occupation.7

Radcliffe’s gold head was adorned by a cross bar for a top instead of a knob, a fact which Munk explained by the statement that Radcliffe very possibly preferred a handle of that kind for his cane as a distinction from that used by the majority of physicians.

It was undoubtedly an icon to boast elevated status:

While the gilt cane, with solemn pride,

To each sagacious nose applied,

Seem’d but a necessary prop,

To bear the weight of wig at top.

Shortly before the opening of the New College of Physicians in 1824, the widow of Matthew Baillie presented its president Sir Henry Halford the Gold-Headed Cane, which had successively been carried by Drs. Radcliffe, Mead, Askew, Pitcairn, and her own lamented husband.

But like many things it has not been without controversy. In 1956 an article in the British Medical Journal entitled “The Gold Headed Cane” declaimed trenchant criticisms of the archaic practices of the Royal College of Physicians, which in turn were stoutly rebutted.8

William Macmichael M.D. Oxon., F.R.C.P., F.R.S. (1783-1839)

Macmichael (Fig 3.), son of a banker, was educated at Bridgnorth Grammar School and Christ Church, Oxford. After graduating in Arts he studied medicine at Edinburgh and St. Bartholomew’s Hospital, London.

Ruined by the failure of his bankers, he practiced in London. He graduated MD in 1816 and was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1817, and of the Royal College of Physicians in 1818. His medical practice was neither large nor prosperous, but he had the good fortune to secure the friendship and patronage of Sir Henry Halford (Vaughan).9 Macmichael was appointed physician to the Middlesex Hospital from 1822 to 1831. Thanks to Halford he was appointed physician-extraordinary to George IV in 1829. The following year saw him as William IV’s physician-in-ordinary. King William gave him his own gold-headed cane, saying that since Macmichael had cured him of gout he no longer needed it. He married Mary Jane Freer and had one daughter, Mary Jane, afterwards Mrs. John Cheese.

He was respected as a congenial, amusing man of “prepossessing appearance.” He published four pamphlets concerning “Scarlet Fever,” “Contagion and Quarantine,” and “Some Remarks on Dropsy.” He wrote seven of the eighteen Lives of the popular book British Physicians (1830).

A stroke in 1836 rendered him paralyzed and aphasic, and he died at 12 Lyon Terrace, Maida Hill, on 10 January 1839 and was buried at All Saints’ cemetery, Kensal Green.

Dr. Thomas Hunt, his great-grandson, owned Macmichael’s annotated, inter-leaved copy of the first edition of The Gold-Headed Cane. Hunt republished it with an introductory memoir and Macmichael’s portrait, painted by William Haynes and owned by Miss Joan Cheese, his great-granddaughter. This facsimile was published by the Royal College of Physicians for its 450th Anniversary.

An anonymous poetic epitaph summed him up:

Here, ripe in years, in wisdom mellow

Reposeth one most learned ‘Fellow’

Who drew an intellectual feast

From musty tomes in Pall-Mall east

Then wrote a book to prove his knowledge

And praise the fellows of the College.

End note

All quotations from the Cane are from: Packard FR.1 Full text of the Gold-headed cane…

References

- Packard FR. The Gold headed cane and its author, William Macmichael.1900. [contains full text of Macmichaels book.]

- https://archive.org/stream/b28039907/b28039907_djvu.txt

- Macnalty AS. The Gold-Headed Cane. Review: Med Hist. 1969; 13(2): 203.

- Garrison & Morton’s Medical Bibliography. 5th edn. ed Jeremy M Norman. Aldershot, Scolar Press 1991. p.1027:6709.

- MacMichael W. The Gold-Headed Cane. A new edition with an introduction and annotation by George C. Peachey. 195 pp. London: Henry Kimpton, 1923.

- Hunt TC. William Macmichael, MD, FRS: Author of The Gold-Headed Cane. J Royal Coll Physicians Lond. 1968;2(4):372-380.

- Silverman ME. The tradition of the gold-headed Cane. The Pharos/Winter 2007: 42-46.

- https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/1747/911eb9c092c0993767212fe7274ef395ed35.pdf

- Wellcome Library. The Gold- headed cane and its author, William Macmichael . https://wellcomelibrary.org/item/b28039907#?c=0&m=0&s=0&cv=4&z=0.1408%2C0.7194%2C0.7001%2C0.3855

- Brain WR, Davidson M, Edwards JL. The Gold-Headed Cane. British Medical Journal 1956;1 (4970-1):791-4., 857-8.

- Packard FR. The Gold Headed Cane And Its Author, William Macmichael. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1914; 4(1): 1–11.

JMS PEARCE, MD, FRCP, is a retired Consultant Neurologist and author.

Summer 2019 | Sections | Literary Essays

Leave a Reply