The tube connecting the inner ear to the throat that may become painfully blocked during a plane landing was described in the sixteenth century by Bartolomeo Eustachi—more often known by his Latin name of Eustachio.1 He constituted, along with Andreas Vesalius (1514–1564) and Gabriele Falloppio (1523–1562), the Anatomical Trinity from which the modern science of anatomy had its birth.2

Very little is known about his life. He was born in 1500, or more likely in 1513,3 in one of three San Severino towns in Italy, probably the one in the Marche.1 Son of a physician, he had a classical education, acquiring such excellent knowledge of languages that he edited the works of Hippocrates and translated from Arabic the books of Avicenna (Ibn Sina). He received his medical degree in Rome and then became private physician to the Duke of Urbino.3 When Cardinal Giulio della Rovere moved to Rome, he accompanied him and became professor of anatomy at the Sapienza University, teaching medical students and carrying out his studies on normal human anatomy. In 1574, while traveling from Rome to attend to the illness of the Cardinal, he died, “in severe pain and almost destitute.”1

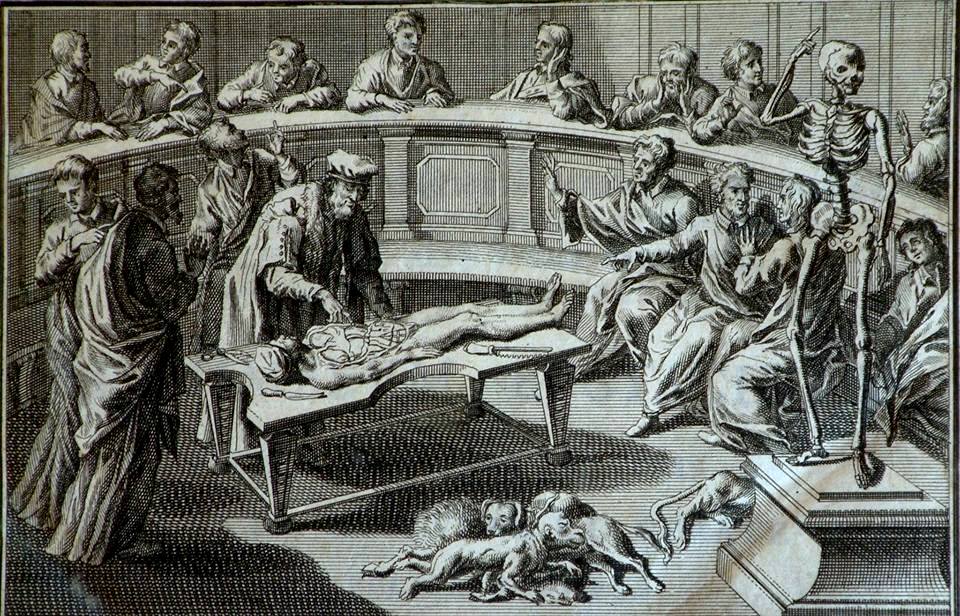

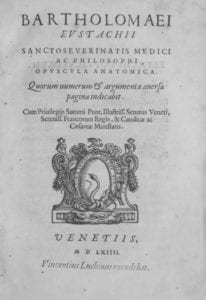

Eustachio produced only one work. It consisted of forty-seven plates, engraved on copper by himself and said to be the first anatomical plates ever produced by this process.4 He carried out this work by using glasses to examine tissue prepared by maceration, injection, or desiccation.4 The text accompanying the plates has unfortunately been lost. The first eight plates dealt with the kidneys and renal circulation. They were published as the Opuscola Anatomica in 1552, nine years after Vesalius’s great work was first printed, an unkind fate denying him “the glory which he should have shared with Vesalius of being known as the reformer of anatomy.”3 Publication of the remaining thirty-nine plates was delayed, perhaps because they were incomplete.3 They were not published during his lifetime, remaining in the Cathedral of Urbino until found by the chief physician to Pope Clement XI, Giovanni Maria Lancisi, now in the same chair at Sapienza as Eustachio, who published them in 1714.4 The overall work consists of six parts, describing the kidneys, inner ear, teeth, bones, head, and vena azygos. In them he describes not only the Eustachian tube but also the adrenal glands, primary and secondary dentition, the sympathetic trunk, some of the branches of the cranial nerves, the male and female genital organs, the vena azygos, and the thoracic duct.

The plates were republished in Amsterdam in 1722 and again in Rome in 1728. They were reproduced in 1744 for teaching purposes by the Leiden anatomist professor Albinus in an atlas comparing Eustachio’s drawings with his own.4 By then Eustachio had long passed into history, now a house-hold name linked to the tube he described, but in life “an unfortunate man plagued by gout and poverty, whose service to a cardinal and professorship at the Studio della Sapienza never advanced his fortunes, and whose intimate career is so little known that even the date of his birth is uncertain.”2

References

- Mezzogiorno A and Mezzogiornio V. Bartolomeo Eustachio. A pioneer in morphological studies of the kidney. American Journal of Nephrology. 1999;19:193.

- Shipley M. Note on two scientific anniversaries. The Monist, 1924; 34:473 (July).

- Two notable anniversaries. British Medical Journal 1913;2:1177 (Nov 1).

- Hilloowala R. Bartolomeo Eustachio: his influence on Albinus and the anatomical models at La Specola, Florence. Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences. 1986; 41:442 (Oct).

Leave a Reply