|

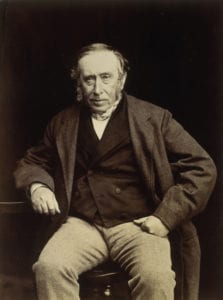

| James Syme, by John Adamson. Scottish National Portrait Gallery, 1855. |

James Syme was born in Edinburgh in the year when Napoleon became First Consul, and in later years came to be called the Napoleon or Wellington of surgery.1-6 As a young man he had an interest in chemistry and at age eighteen developed a method of making textiles impermeable to water by impregnating them with a coal tar derivative, so that they “afforded complete protection from the heaviest rain.”4 He did not apply for a patent, “being then about to commence the study of a profession with which consideration of trade in those days did not seem consistent.”4 Credit and fortune for this discovery later went to Charles Mackintosh, a Glasgow business man who had his name applied to the raincoat and whose name became known to many who have never heard of James Syme.3 Many years later Syme reflected that the only profit he gained from his discovery was the confidence he acquired in solving a difficult problem.3

He had been born in a family of “good circumstances” and attended the local high school where Sir Walter Scott had been educated, but he also had “the advantage of a private tutor.”4 While pursuing his interest in chemical experiments, he also became interested in botany and anatomy. At age fifteen he entered the University of Edinburgh and spent two years taking art classes. He did not graduate from the University, and as the professor of anatomy Monro Tertius was not a popular teacher, he like many other students attended classes given by the famous private teacher Dr. John Barclay (1817–1818).4,5 The next year he became assistant demonstrator in dissections to his distant cousin and later rival and competitor, Robert Liston.4 When Liston decided to devote himself entirely to surgery, Syme took over his class.

In 1820 Syme was appointed superintendent of the Edinburgh Fever Hospital, where he himself caught a severe attack of some infectious disease.4,5 In 1822 he was elected house surgeon at the Edinburgh Royal Infirmary, and spent some months studying in Paris, attending the clinic of Dupuytren, and taking a course in operative surgery under Lisfranc.5 On his return to Scotland he acquired the right to practice medicine by passing the examinations to become Member and then Fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons, but he never pursued a university degree.

In 1824 Syme performed an amputation at the hip joint, the first time such a procedure had been performed in Scotland.3,4 This was the beginning of a brilliant surgical career in which he performed a wide variety of operations and published a great number of articles. He entered into partnership with Robert Liston, but they soon quarreled and remained bitter enemies until 1840, when they reconciled.4 By 1826 he had abandoned the teaching of anatomy, apparently because it had become too difficult to obtain cadavers for dissection, and devoted himself entirely to surgery. Being denied an appointment at the Royal Infirmary, he opened a private surgical home (at Minto House) with twenty-four beds, an operating room, and a lecture theater.2,4 During his four years there he built a reputation for his skill by successfully treating patients whom others deemed to be inoperable. His class was limited to forty students even though many more applied, and he introduced the practice of amplifying his lectures by having patients brought into the lecture room, where students, “comfortably seated,” could “learn the principles of treatment, with reasons for choosing the method preferred,” thereby making “an impression at the same time on the eye and ear, which is known by experience to be more indelible than any other.”3

In 1833 Syme was appointed Clinical Professor of Surgery at the University of Edinburgh and he taught there for thirty-six years. He continued his methods of teaching surgery, and his surgical service became the mecca of surgery in Scotland. He also developed a successful private practice and would visit his patients in an elegant yellow carriage drawn by a pair of white horses.2 By 1835 he was the leading surgeon in Scotland.3 Among the surgical feats for which he is remembered are successful amputation at the hip joint (1823),4 removing a four and a half pound tumor of the jaw that had been regarded inoperable (1828),3 devising a method of amputation at the ankle that became associated with his name, relieving urethral obstruction by an operative perineal approach, and experimentally investigating the role of the periosteum in forming new bone. He carried out operations for fractures of the femur, arthritis of the elbow, obstruction of blood vessels, treatment of aneurysms, cancer of the tongue, and urological and rectal problems.3 He once “boldly opened” into a traumatic aneurysm of the left carotid artery, tying the artery above and below the wounded part, thus saving the life not only of the patient but also saving the man who had stabbed him from being hanged.3,7

In 1862 he was made surgeon in ordinary to the Queen in Scotland, received the French Légion d’honneur, a Danish knighthood, and later, several other orders in Britain and continental Europe. He wrote several surgical books and manuals, and numerous articles on a variety of surgical subjects. These articles are often quite descriptive, such as when he intervened to remove a fish bone that had become impacted in a woman’s esophagus.8 On another occasion he described how he successfully removed a coin that had become stuck for three months in a patient’s esophagus, and he marveled how it could have stayed there so long without causing ulceration of the mucous membrane on which it rested. The patient, a young Swede, “son of respectable parents in Gothenburg” who had come to Scotland to study agriculture, had swallowed the coin accidentally while demonstrating his skill of throwing it in the air and catching it in his mouth. The coin looked like one of King George’s pennies but on closer inspection proved to be a Swedish coin of the same value!9

Dr. Joseph Bell, Conan Doyle’s Edinburgh prototype for Sherlock Holmes, described Syme as a man under the middle height, squarely and solidly built about chest and shoulders, with small hands and neat feet, active on his legs even to old age. His dress was quite peculiar—a black evening coat with a light colored waistcoat and trousers and a pretty, original tie generally of black-and-white or blue-and-white checked pattern.6 He lived simply, walking into town unless the weather was very bad, attending punctually at the infirmary and then at his office, and in the afternoon returning to his garden. He dined early and went to bed early. He was a shy reserved man whom strangers often found distant and at first grim. He was a loyal friend but a determined foe if he fought you.3,6 In the operating room he was remarkable for his extreme quietness of manner and movement. He rarely moved his feet or even his shoulders, his work being done mainly from elbow and wrist. Regarded as not particularly dexterous or rapid, he had hands that were absolutely steady, and the knife always went exactly where he wanted it to go. He rarely spoke during surgery and expected his assistants to also be quiet.2 His dressings were simple, he encouraged wound drainage, and even in the days when antiseptic medicine was still unknown he had many amputation stumps heal promptly by first intention.6

On the death of Robert Liston, Syme accepted the position of chair of clinical surgery at University College in London (1848). His term there was brief and not successful, his style being different from the London surgeons, and also because he became involved in various controversies. After a brief stay, returned to Edinburgh and was reinstated in his professorial position.2 In 1849 he was elected President of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh. He was effective in introducing some reforms in medical education, advocating the appointment of a board to regulate it, but was met with opposition to some of his proposals.

After the introduction of anesthesia, Syme used chloroform for his surgeries. He was an enthusiastic supporter of the method of antiseptic surgery of his son-in-law Joseph Lister, who had married his daughter Agnes.1,3,10,11 In his lectures he came out in support of a practical system of education, writing that “the great evil of modern medical education is, that it has become a preparation, not for discharging the duties of a profession, but merely for passing examinations which, for the most part, imply neither an accurate knowledge of facts nor the possession of sound principles, being simple affairs of memory loaded with dry terminology, to be thrown overboard at the earliest opportunity.”10 He remained in good health until the age of seventy, making frequent trips between Edinburgh and London, before succumbing to cerebrovascular disease.4 He is remembered as of one of the last great surgeons and teachers before the momentous changes that revolutionized surgical practice in the last decades of the nineteenth century.

References

- Nova and Vetera. The Napoleon of Surgery. British Medical Journal ,1954;151. Jan 16

- Williams Harley. Master of Surgery. p100. Pan books Ltd, London, 1954.

- Graham JM. James Syme. British Journal of Plastic Surgery. 154;7:1.

- James Syme. British Medical Journal ,1870;2:21-24, Jan 16

- Royal College of Surgeons. Plarr’s Lives of the Fellows. Syme James. 2013: April 10.

- Literary Notes. British Medical Journal 1908; 1:514, Feb 29.

- Annandale T. Early days in Edinburgh. British Medical Journal 1902; 2:1842, Dec 13.

- Syme J. Clinical Observations. Oesophagotomy. British Medical Journal 1861; 1:193, April 24.

- Syme J. Clinical Observations. Oesophagotomy for the removal of a copper coin which had remained for three months in the gullet. British Medical Journal 1862; 1:299. March 22.

- Syme J. Concluding lecture of a winter course on clinical surgery. British Medical Journal 1868; 1:371. April 18

- Syme J. Illustrations of the antiseptic principle of treatment in surgery. British Medical Journal 1868; 1:1. January 4.

GEORGE DUNEA, MD, Editor-in-Chief

Leave a Reply