In 1879 an armed conflict known as the War of the Pacific broke out between three South American nations, pitting Chile against a Peruvian-Bolivian alliance in a dispute over land rich in minerals, especially sodium nitrate. The Chileans defeated their adversaries by land and sea, their armies invading Peru, occupying Lima, eventually annexing valuable territory on the Pacific coast, and leaving Bolivia a landlocked country. Peace was restored in 1883, but bad blood persisted between Chile and Peru, even among doctors, who disagreed about the relation between two diseases prevalent on the high mountain ranges of the Andes, one chronic and lingering, the other acute and often fulminating.1-6

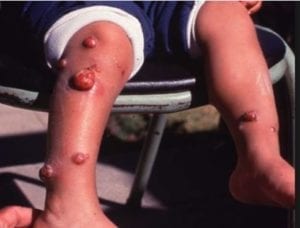

The chronic disease, verruga peruana, may well have existed since pre-Columbian days, as shown by wart-like lesions depicted on ancient Inca artifacts.1 It is essentially a cutaneous disease consisting of multiple vascular nodular eruptions on the skin and mucous membranes, sometimes accompanied by fever and joint pains. The acute disease, Oroya fever, is a severe illness with fever, hemolytic anemia, and microvascular thrombosis. It may affect different systems of the body and variously manifest itself as seizures, menigoencephalitis, jaundice, gastrointestinal involvement, or angina. Many of the victims become immunosuppressed and susceptible to superinfection by salmonella or toxoplasmosis, and the untreated overall mortality rate is as high as a 40%.1-6 The disease was called Oroya fever after the 1875 outbreak that killed many of the construction workers building a high altitude railway line between the Peruvian coastal city of Callao and the mineral rich city of La Oroya. It is likely, however, that the disease was known even in the pre-Inca period and that it was responsible for an outbreak causing the loss of one quarter of the men of the invading armies of the conquistador Francisco Pizarro.1-4

There had long been a suspicion that the two diseases were related but there was no proof. In an argument colored by the recent rivalry between the two nations, the Chilean physician Izquierdo had insisted that the two diseases were unrelated.1,2 But many Peruvian physicians, such as Tomas de Salazar, believed that the diseases had a common cause.1-6 Because of the recent interest spurred by the outbreak at La Oroya, the Free Academy of Medicine in Paris had offered a prize to persons contributing to the understanding of these diseases. Among the contestants was Daniel Alcide Carrion, a twenty-eight year old medical student at the San Marcos University in Lima. Born in Quito, Ecuador, he was the son of a physician who died in a riding accident when Daniel was eight. Sent to live with his mother’s relatives, he moved to Lima at age fourteen and began to study medicine in 1878. But progress was slow, the war interrupting his studies and delaying his graduation.1-6

It was the practice at the time that medical students were required to submit a thesis on an original research topic before being allowed to graduate. Daniel had already participated in clinical studies on the course of verruga peruana, which was suspected to be an infectious disease. His interest was to study its pathogenesis and prevent its spread, and not, as has often been misstated, to determine its relation to Oroya fever.2 The story of what ensued has been told many times.1-6 On August 27, 1885 he took blood from a verruca near the eyebrows of a fourteen year old boy, experienced some difficulty in inoculating himself in the arm, and sought help from a colleague to do so. He became ill after twenty-one days, developed fatigue, fever, and joint pains, then hematuria, hemolysis, anemia, and increasingly severe symptoms. He remained optimistic, waiting to improve and be saved once the verrucas would appear; and only as his condition worsened and he was near death did he realize that he had inoculated himself with the dreaded Oroya fever and that indeed he had provided definitive evidence that it and verruga peruana were manifestations of the same infection.1-6

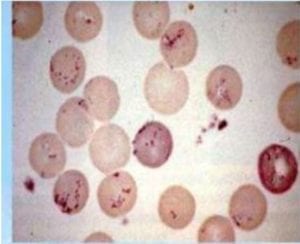

Since his time much has been learned about this disease. Restricted to the South American Andes, mainly Peru, Ecuador, and Colombia, it is transmitted by the bite of the Lutzomyia sandfly which lives at altitudes of 600-3200 m above sea level, also by blood transfusions and from mother to child. It has now become eminently treatable with a variety of antibiotics, traditionally a combination of tetracycline and chloramphenicol. In 1905 the Peruvian physician Albero Barton, while studying the blood smears of fourteen patients suffering from Oroya fever, discovered its causative organism, an intra-erythrocyte bacillus now named Bartonella bacilliformis. Its mechanism of transmission was confirmed in 1926 by Noguchi in experiments on monkeys.

Officially named Bartonellosis, the disease is often referred to as Carrion’s disease, in remembrance of the young student who died while studying it. For his experiment he has gone down in history as a hero and a medical martyr, with memorials, hospitals, and universities named after him, stamps issued in his honor, and statues erected in his memory. Young and ambitious, he was at the age when ”no young man believes he shall ever die,”7 when young men are fearless and ready to undertake any perilous act. It is a critical time because nature has made the adolescent male of our species unable to understand danger, these invincible warrior instincts coming from our tribal past and creating a deadly rite of passage.8

References

- Gomez,C. Ruiz,J. Carrion’s disease, the sound of silence. Clinical Microbiology Reviews 2018;31,1.

- Poma PA. Daniel A Carrion. Illinois Med Journal 1988;174:27.

- Schultz MG. Daniel Carrion’s experiment. New Engl J of Med 1968, 278:1323

- Cadena J, Anstead J. A medical student named Daniel A Carrion and his fatal quest for the cause of Oroya fever and Verruga Peruana. Reprinted from www. antimicrobe.org

- Chatterjee P, Chandra S, Biswas T. Daniel Alcide Carrion and a history of medical martyrdum. Journal of Medical Biography 2015;23:224

- Steensma, DP, Monton VM, Shampo MA, and Kyle R. Daniel Alcides Carrion – Peruvian hero and medical martyr. Mayo Clinic Proc 2014; 89:E 55

- Hazlitt W. On the feeling of immortality in youth. Winterslow 1850; 45. Oxford University Press

- Borg M. Dangerous Inheritance. Hektoen International spring 2019, volume 11, issue two, (in personal narratives)

Leave a Reply