Andrew Williams

Frederick O’Dell

Northampton, United Kingdom

On July 9, 1748 Dr. James Stonhouse, physician at the Northampton Infirmary (United Kingdom), published “A Friendly Letter to a Patient just admitted to an Infirmary.”1 Later that year, after some minor revisions, the text was reprinted as “Friendly Advice to a Patient,” which for the next century and beyond was used in voluntary hospitals throughout England, North America, and Holland.

|

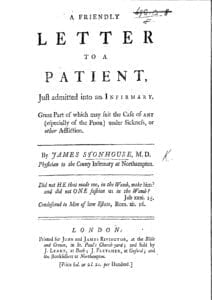

| Figure 1: Dr. James Stonhouse |

Brief Biography of Sir James Stonhouse

James Stonhouse, later knighted, (1716-1795) studied at St. John’s College, Oxford University (1732), where as an undergraduate he wrote a pamphlet against religion, which went to three editions. He came to Northampton in 1743. There having come with a reputation of “a most abandoned rake and an audacious deist” he heard the Reverend Dr. Philip Doddridge (1702-1751) speak at a funeral and underwent a profound religious conversion.2 Stonhouse was the major force behind the establishment of Northampton Infirmary. He later took up Holy Orders becoming Rector of Cheverell Parva in Wiltshire.3

From “Friendly Letter” to “Friendly Advice”

The Gentleman’s Magazine listed the twenty-five-page leaflet “A Friendly Letter to a patient, just admitted into an Infirmary” in its August 1748 edition, costing 6d4 (Figure 2). Stonhouse, believing this was his duty, admitted this book would appear “somewhat foreign to the province of a Physician.” He saw illness as “…under the afflicting Hand of God. That you are under some illness, or unhappy accident…and that you are so poor as not to be able, at your own expense, to procure proper relief.”1

The book encourages the inpatients, if they are well enough, to participate in all ward religious activities. They were asked to assist where possible with ward nursing duties under the matron’s direction, and those who were literate were encouraged to teach other illiterate patients to read and write. “…there are many ways by which you may, perhaps, be useful in the infirmary…by reading to others, by working for them and by teaching them to read… [this] under the direction of the Matron…”1

When a patient felt their cure was not progressing as well as for other patients, Stonhouse encouraged patients to “…be not impatient; nor by any means envy…” and “…suspect not the skill or the integrity of those who have the care of you, for the Physicians of Princes are often unsuccessful… [even] the most judicious physicians themselves are at last obliged to submit to death.”1

However there was a complaints procedure and after discharge the patient had a public obligation of gratitude. Stonhouse says, “And as for what may have been amiss, which I hope in such societies will be very little, do not blaze it abroad, to promote a prejudice against such places, which would be very ungrateful, and very mischievous; but give proper hints of it to those that may have it in their power to rectify what is amiss.”1

It was an explicitly Christian text at a time when its author did not consider other faiths or atheism as valid. “You must know it, if you believe there is a God, and a Providence, which is so evident on the common Sense of Mankind, that one would hope none can so much as question it.”1 However the text strongly emphasized the benefits of infirmary care to patients who, being poor, would otherwise have been unable to afford this.

“You are in a place where you are surrounded with many Mercies, which therefore, you ought to be very thankful for – thankful to God, as well as to your human Benefactors. You have convenient Lodging, and that is a great Mercy – an easy warm bed, a good House around you … You have attendants to wait upon you, as your Necessities require, Night and Day – you have Food sufficient and proper – such as may comfort and support Nature, without feeding your Distemper – And then you have the most suitable Medicine, in their greatest perfection, prescribed by PHYSICIANS, judged (by those who have consigned this office to them) to be of approved Skill and Experience – Such persons cannot be under the least Temptation to overload you with them; a Circumstance which is of no small Importance – These Gentlemen visit you at proper Seasons, they are ready to attend to you at any time, if an extraordinary Circumstance in your Case should make it necessary. If you are wounded, or under the Agony of a broken Bone, or in other Circumstances, that require the important Aid of SURGEONS, Persons selected from many others of that useful and necessary Profession are ready to attend you with their assistance – which would else, perhaps have been so expensive to you, that you might have been ruined by procuring it, or perished for want of it.”1

|

| Figure 2. Dr. Stonhouse’s Friendly Letter to a Patient (1748) |

The initial print run of “A Friendly Letter” remains unknown but later that year (with the same frontispiece dated July 9th 1743), it was reprinted, after minor amendments, as a small book re-titled “Friendly Advice to a Patient.” One example of cut text was his mentioning in a “Friendly Letter” that patients could close the curtains around their bed to make a “closet” for prayer. An example of additional text was placed in the footnotes of “Friendly Advice”: “This Friendly Advice to a patient…is given away at the Northampton Infirmary (and at several others) to all the Out, as well as in-patients, on their admission, by the Chairman, who strictly injoins them to make proper use of it; not only while they continue patients, but so long as it shall please God to spare their lives after they are discharged.”5

“Friendly Advice to a Patient” in this format, twenty-six editions between 1749-88, was used throughout English voluntary hospitals,6 abroad in Holland, the American Colonies,7 and Australia.8 (The fifteenth edition ran to 6,000 copies.)9 In 1835 it was combined in a new edition, with several other of Stonhouse’s works.10 By 1844 the catalogue of the “Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge” related “…the matter is better than the style…” which appears “…somewhat heavy and old fashioned.”11

Conclusion

In the eighteenth century, voluntary hospitals arose as locally funded charitable institutions to provide care not for the wealthy, but for the poor. Religious belief was a cornerstone for their establishment and continuance.12 Although other patient literature must surely exist from the mid-eighteenth century, nevertheless it was Stonhouse’s “Friendly Advice” that dominated during this period and beyond.

For twenty-first century doctors the rules concerning religious belief are different from those of the time of Dr. Stonhouse. The General Medical Council’s “Personal Belief and Medical Practice” states: “You must not express your personal beliefs (including political, religious and moral beliefs) to patients in ways that exploit their vulnerability or are likely to cause them distress.”13 In a multicultural and largely post-religious environment, it is clear for any devout healthcare professional that however well intentioned, sensitive, and respectful, such a profession of faith, even so far as offering the comfort of prayer, may not be welcome and can lead to disciplinary action.14,15 Clearly Dr. Stonhouse would be appalled at the introduction of such rules. Recently, there has been a call for healthcare professionals to declare any religious belief.16

Patient literature has evolved in Northampton since 1748. Stonhouse’s “Letter to a Patient/Friendly Advice” is essentially a religious, rather than a hospital, text. The Northampton General Hospital website allows vastly more information, delivered real time to a far wider audience than any practical booklet alone could provide; all through a medium utterly inconceivable by Stonhouse.

Northampton General Hospital to this day remains an institution where patients are “surrounded with many mercies” providing free healthcare for all at the point of delivery. Such healthcare remains as relevant today as when Stonhouse related in 1748 “so expensive to you, that you might have been ruined by procuring it, or perished for want of it.”1

References

- Stonhouse J. A friendly letter to a patient, just admitted into an infirmary: great part of which may suit the case of any (especially of the poor) under sickness, or other affliction. London: Printed for John and James Rivington, at the Bible and Crown, in St. Paul’s Church-yard; and sold by J Leake, at Bath; J Fletcher, at Oxford; and the booksellers at Northampton 1748. (A fully accessible on line version of this complete text from Yale University (US) is available courtesy of the Hathi Trust at https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=yale.39002088449781;view=1up;seq=5) accessed April 19th 2018.

- Deacon M. Philip Doddridge of Northampton. (Northampton: Northamptonshire Libraries 1980), 105. [These are the views of Dr Rev Philip Doddridge of Sir James Stonhouse].

- Waddy FF. A history of Northampton General Hospital 1743 to 1948. (Northampton: The Guildhall Press 1974), 154.

- Advert for Stonhouse J. A friendly letter to a patient, just admitted into an infirmary. In: The London Magazine, or Gentlemen’s Monthly Intelligencer 1748 Volume 17. https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=CvoqAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA384&1pg=PA384&dq=%22friendly+letter+to+a+patient%22&source=b1&ots=EvDYnUtiST%sig=kuft_AtRdQpbVix1t70rAtD6x3U&hl=en&sa=

X&ved=2ahUKEwiCwOvqwqvaAhULWsAKHZWWAgk4ChDoATAEegQIARAB#v=onepage&q=%22friendly%20letter%20to%20a%20patient%22&f=false Accessed April 6th 2018. - Stonhouse J. Some friendly advice to a patient, advice in case of amendment. Northampton July 9th 1748. In: Stonhouse T. Ed. Religious tracts on various subjects a new edition. (London: Longmans 1821). The 12th edition can be found online at https://books.google.co.uk/books?h1=en&1r=&id=P6pgAAAAcAAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PR1&dq=some+friendly+advice+stonhouse&ots=VPrOm4TqCT&sig=QNqed7aU7WZnc4W_5jwvytPpn_g#v=onepage&q=

some%20friendly%20advice%20stonhouse&f=false Accessed March 22nd 2018. - Nuttall GF. Calendar of the correspondence of Philip Doddridge DD (1702-1751). Historical Manuscript Commission JP26. (London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office 1979), 296.

- Stonhouse J Sir. 1716-1795 entry on OCLC World Cat. http://worldcat.org/identities/1ccn-n85067392 Accessed April 6th 2018.

- Stonhouse J. A friendly letter to a patient, just admitted into an infirmary. 1748 3rd edition. (London: printed for John and James Rivington 1748). https://trove.nla.gov.au/work/16741168 Accessed April 10th 2018.

- Langford P. A polite and commercial people England 1727-1783. (Oxford: Oxford University Press 1998), 138.

- Stonhouse J. Prayers for the use of private persons, families, children and servants, including Friendly advice to a patient, etc. New edition 1835. In: England. Church of England. Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge. Religious tracts, etc. Volume 6, 1836.

- Anonymous. Life of the Rev Sir James Stonhouse, BART., MD., with extracts from his tracts and correspondence. (Oxford: Printed by I Shrimpton. MDCCCXLIV 1844).

- Fissell ME. Patients, power and poor in eighteenth century Bristol. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1991), 1.

- General Medical Council. Personal belief and medical practice. https://www.gmc-uk.org/Good_practice_in_prescribing.pdf_58834768.pdf Accessed March 19th 2018.

- Daily Mail newspaper. http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2121497/Christian-doctor-sacked-emailing-PRAYER-hospital-colleagues-raise-spirits.html Accessed March 22nd 2018.

- Daily Mail newspaper. http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-4021094/Nurse-sacked-offering-pray-patients-despite-call-equality-watchdog-end -persecution-Christians.html Accessed March 22nd 2018.

- Smith, R., and J. Blazeby. Why religious belief should be declared as a competing interest. BMJ 2018 361:k1456 (published 12th April). https://www.bmj.com/content/bmj/361/bmj.k1456.full.pdf Accessed April 16th 2018.

ANDREW N. WILLIAMS, PhD, is a consultant community pediatrician, medical historian, and playwright. A full-time NHS consultant specialist in pediatric neurodisability and community child health, he has published on different aspects of child health between the 16th–19th centuries and has taken his PhD at the University of Birmingham on the history of pediatrics and child health 1550–1750.

FREDERICK J. O’DELL, studied Family and Community History with the Open University and holds a Masters Degree in Library and Information Science. He has written on; library use in the NHS, Dr. Gosset’s icterometer, early Northamptonshire neonatal pediatrics, and the invention of the lithotrite. He is a historical archive volunteer at Northampton Hospital.

Spring 2019 | Sections | History Essays

Leave a Reply