|

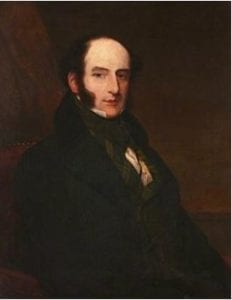

| Robert Liston (1794–1847), FRCSEd (1818). Portrait by Samuel John Stump (1778–1863), 1847. The Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh via Wikimedia. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. |

Samuel Johnson, a man of strongly held prejudices, had a low opinion of most foreigners, and this included the Scots. James Boswell, his biographer and a Scotsman himself, records how Johnson patronizingly would declare that the best roads lead from Scotland and that much could be made of a Scotsman “if he be caught young.” Yet by the standards of his times, Robert Liston was no longer in the prime of his youth when at the age of thirty-five he turned his back on Edinburgh and took the high road to London.

Born in 1794, the son of a Scottish minister, he entered Edinburgh University in 1808 and two years later began to attend lectures in surgery and anatomy. He then became an assistant and demonstrator in anatomy, and remained in that position until 1815, when he was appointed house surgeon at the Edinburgh Royal Infirmary. He continued his training in London at the London Hospital and St. Bartholomew’s Hospital, and by the age of twenty-two was admitted to the Royal College of Surgeons. He worked in Edinburgh between 1818 and 1828, and proved to be an excellent surgeon, operating with success on cases that other surgeons considered incurable, but in time became unpopular because of his abrasive argumentative manner, his tendency to overly criticize incompetent surgeons, and his involvement in a series of disputes.

On moving to London in 1835, he became professor of clinical surgery at University College Hospital and remained there for the rest of his life. He developed a large practice and fortune, becoming one of the foremost surgeons in the city. At the time when speed was essential but cleanliness of little importance, he would always remove his frock coat, put on a clean apron, and wash his hands before operating. He developed a new incision for amputating legs and using a long knife with both edges sharpened became “the fastest knife in the West End.” His speed was such that he was able to remove a leg in under three minutes, while onlookers gasped in amazement and terrified medical students would hold the leg and restrain the patient. Before operating he would ask the audience to “time me, gentlemen.” Stories of his feats abound, some perhaps apocryphal, such as that during one amputation he removed not only the patient’s leg but also a testicle and two of his assistant’s fingers. Once he was said to have swung his knife so widely that he slashed through the coat tails of a distinguished surgical spectator who dropped dead from fright. Also, in an argument with his house surgeon as to the nature of lump in a boy’s neck, he plunged his knife into it, causing arterial blood to spurt out from what turned out to be an aneurysm. He is said to have removed in four minutes a forty-five-pound tumor of the scrotum that the owner had been carrying about in a wheelbarrow.

Between 1835 and 1840 he performed amputations on sixty-six patients, of whom only ten died, a respectable result at a time when postoperative infection and gangrene was common. He had good clinical sense and knew when to operate. He was considerate to his patients, critical of unethical behavior by the members of his profession, made significant advances to the practice of surgery, and stressed the importance of a good knowledge of anatomy. He treated his students roughly, expecting the highest level of performance.

He is credited to have performed the first operation in Europe under ether anesthesia. The news from Boston had reached England by the ship the Arcadia, but it actually appears that Liston was anticipated by a few days by William Scott, a surgeon who heard the news from the ship’s captain. Be that as it may, it was Liston who operated on 21 December 1846 on a patient suffering from an infected leg. Saying that he was about to try this Yankee dodge, he amputated the leg in five minutes, at which time the patient woke up from the anesthetic and asked to be taken back and not have the operation done. Impressed, Lister is said to have commented that this “beats mesmerism hollow,” perhaps another apocryphal story, yet this was the beginning of a new era in surgery. But Liston did not live to see it flourish, because a year later he sustained a sailing accident in which a blow across the chest caused a fatal hemorrhage, perhaps from an aortic aneurysm.

Further reading

- Jones, AJ. Nesbit Jr, RR. Holsten, SB: Time me gentlemen, Am Coll Surg. https://www.facs.org/~/media/files/archives/shg%20poster/2016/05_liston.ash.

- Williams, Harley: Masters of Medicine, Pan Books LTD, London, 1954.

- Gordon, R: Great Medical Disasters, Hutchinson & Co., 1983.

- Wright, AS, Maxwell IV, PJ: American Surgeon, January 1, 2014.

- Schofield AL: Robert Liston (1794-1847). British Journal of Plastic Surgery, 1950;3:227.

GEORGE DUNEA, MD, Editor-in-Chief

Leave a Reply