Mariel Tishma

Chicago, Illinois, United States

|

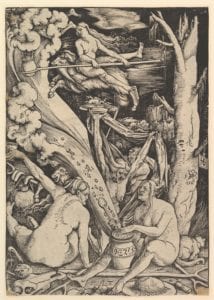

| The Witches. Hans Baldung (called Hans Baldung Grien). 1510. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. |

The image of a woman – a witch — working over a bubbling cauldron filled with stomach-turning substances is a staple of both horror and more family friendly media. One such example is Shakespeare’s Macbeth, specifically the “Double, double toil and trouble” speech given by the three witches in Act IV. The witches list off dozens of ingredients including the eye of a newt, the tongue of a dog, and the scale of a dragon.1

It is entirely possible that Macbeth’s potion is fiction, simply meant to shock audiences by furthering the supernatural horror of the play. However, it has been suggested that “all of the ingredients in the witches brew are simply ancient terms for herbs, flowers and plants” used by herbal healers.2

Herbalists may have used these folk names in an attempt to protect their practice. One ancient “spell book” explains that misleading names were chosen for ingredients due to “the curiosity of the masses.” The general public, the writers believed, “do not take precaution” when using herbal cures or magic, and so must be discouraged by using frightening or disgusting names.3

Herbalism can be considered traditional medicine, a supplemental healthcare practice designed “to treat, diagnose and prevent illnesses or maintain well-being.”4 Folk names for remedies may have been used as protection against patient misuse, as well as establishing a common vocabulary between professionals, potentially comparable to the usage of language in medicine today.

Of course the witches in Macbeth are an exaggerated, supernatural image, which makes it hard to find their medical connection. However the inspiration for the witch at large had to come from somewhere. It is entirely possible Shakespeare found his inspiration in herbal healers or underground medical workers he may have encountered at the time of writing. The work of these healers, thanks to skewed reputations and folk names, could appear sinister to the uninitiated, despite most potions containing mainly “intoxicants or folk remedies.”5

Additionally, while Shakespeare presents his witches within the bias of his time, Macbeth is set in the mid eleventh century, a time when herbalism was more widely practiced and female herbalists, and female health workers in general, were more common.6

Beginning in the thirteenth century, female health workers faced intense opposition.7 It is around this time that medical practice was being regulated and licensed, with women barred from formal medical training and forced out of practice all together.8 When caught, women practicing in secret without licenses were often called witches.9

This also lends insight into why herbalists may have used coded language for their treatments. If an investigator was too frightened of what a woman could do, or could not prove she was practicing medicine at all, it was less likely she would be persecuted.

It is possible, then, to explore the list of ingredients provided by the witches in Macbeth as a recipe for a specific medicine treating a specific list of symptoms. To translate the code, it is useful to consult both the resources that remain and the ones that have been reconstructed by modern herbalist traditions.

Since most folk remedies included multiple herbs, there are nearly thirty potential ingredients in Macbeth’s medicine. All potential herbs and their summarized usages are listed in the table below. The most significant herbs – whether for medical diagnosis, their danger, or simply for being unusual – are explored further.

One of the first ingredients – the “fenny snake” — can be interpreted as part of a snake or a snake-like animal. The leech is a snake-like animal that has been used in medicine for bloodletting since ancient times.10

The infamous “eye of newt” likely refers to mustard seeds, especially black or spotted mustard seeds, which could resemble the eye of a very small animal.12 Mustard seeds would be ground for use in mustard plasters, a treatment designed to increase bloodflow13 and to treat anything from pneumonia to back pain.14

Both “tongue of dog” and “tooth of wolf” have logical associations based on name — houndstongue15 and wolf’s bane — though tooth of wolf could also be translated as club moss.16

Houndstongue and wolf’s bane can also both have seriously harmful effects. Houndstongue has been used to treat diarrhea but is not recommended for ingestion.17 Wolf’s bane, also known as monkshood, is initially stimulating but eventually paralyzes.18

There was no direct reference to a “blind worm” or its sting in the sources used, however, blind eyes often refer to poppy seeds.19 Wormwood, with its obvious name connection, is an herb with properties similar to the hallucinogenic mugwort. Poppy seeds, well known for their sedative effect, produce opium, the derivatives of which have been used as a pain reliever.20

“Gall of goat” is one of the more interesting ingredients. It refers to the stomach of a goat, which can be interpreted literally as a mystical bezoar stone. A bezoar is a mass that develops in the stomach of a ruminant in order to aid digestion. These were, according to legend, able to cure posioning.21 It is also believed “gall of goat” could refer to honeysuckle or St. John’s Wort.22 Honeysuckle is good for treating digestive disorders23 while St. John’s Wort is one of the few herbs still used in modern medicine as a dietary supplement treating depression and other mental health conditions.24

Yew and hemlock are both referenced by name and are both highly toxic. Yew was previously used as an abortifacient,25 and hemlock had been used in folk medicine to treat joint pain, stiffness, and spasms.26 Neither of these herbs are recommended for use today, and their inclusion (among other poisons) in a healing mixture runs counter to the idea of herbalists as medical professionals. However, in a medico-mystical practice, such as historic herbalism, herbs closely associated with death may have been perceived as extremely powerful, and utilized for their potential ability to amplify other medicines in small doses.

There is also the simple fact that Macbeth is a crafted text, which skews its medical quality, and Shakespeare may have included these herbs to frighten his audience and amplify tension. Those who knew what yew and hemlock could do would be wary of a draught containing them.

The last ingredient referenced, “baboon’s blood,” is also the only one that is translated back into something mystical: the blood of a spotted gecko.27 Curiously, the spotted gecko is known for its ability to self-heal, as when spotted geckoes lose their tails they are able to re-grow them. “Baboon’s blood” is not the only ingredient that remains gruesome, though, as the “witches’ mummy” likely references dried human remains – used in medicine regardless of effectiveness until nearly the 1920s. Neither help to dispel the nonsensical reputation of medieval medicine.

Each of these herbs taken individually treat a number of disorders, but after finding the average of their possible uses, the three most common types of symptoms include gastrointestinal or digestive problems, skin problems, and respiratory problems. These do not easily overlap into one cohesive diagnosis. However, combining digestive issues with symptoms lower down the list — in this case aches and pains and mood changes — suggests a potassium deficiency.

This is reinforced by the inclusion of plantain or banana, another potential “fenny snake.”28 As a fairly exotic ingredient in context, it stands out, and interestingly is a significant source of potassium.

Respiratory issues could be explained by a concurrent cold or flu and the skin problems would easily be acquired through everyday work. Both respiratory and skin problems could also be manifestations of further nutritional deficiencies. Stimulating appetite was one of the lesser effects of the listed herbs, but tarragon (translated from “scale of dragon”) serves no other purpose than stimulant, which also suggests a nutritional diagnosis.

Drawing any conclusion from a list like this requires many layers of assumption and speculation, meaning it may or may not be accurate. But treating the material in a more serious way can be a reminder that medical practioners in the past were doing the best they could with what was available to them. It is easy to dismiss herbal remedies and focus on “what is thought to be a more interesting aspect of the writings: superstition and magic.”29 For example, some herbal texts specified using a copper knife on certain herbs and prohibited iron. While this may seem like alchemical guesswork, later chemical analysis discovered that the use of copper could produce copper salts, an additional medicinal component.30 Further, copper and copper alloys have bactericidal properties.31 The use of copper not only in knives but cooking vessels (and cauldrons) may have helped purify potential treatments.

With this knowledge, herbs and tools of the past may serve as sources for medicinal discoveries of the present. Around 25% of modern medicines have been derived from plants that were used in traditional herbal healing.32 One well known example of this is aspirin, which was distilled from willow bark.33 It is not unbelievable that willow bark was used in the past to treat inflammation or pain, as aspirin is today.

While it is true that herbal treatments are largely unproven and potentially unsafe, history presents a long list of substances with potential. The unrestricted administering of plant remedies is not an effective medical practice, as even the herbalists of old knew, but rigorous study can weed out the dangers and allow for potential new cures to blossom, no newts required.

| Folk name | Potential Herbs | Usages (condensed) |

| Toad / toad entrails | Toad Flax | Anti-inflammatory, diuretic, digestion problems, cure wounds |

| Fillet of a fenny snake | Leech (small snake) | bloodletting |

| Yarrow (boggy plants) | Anti-inflammatory, anti-edema, irritability | |

| Bistort (boggy plants) | Snakebite, astringent, diarrhea and digestive disorders | |

| Plantain (boggy plants) | Diarrhea and other GI problems, snakebite and worms, provide potassium | |

| Snake Root | Diarrhea, snakebite, cough | |

| Eye of newt | Mustard seed, especially with black spots | Used in mustard plasters to improve circulation |

| Toe of frog | Bulbous Buttercup | Skin, GI, respiratory problems |

| Wool of bat | Holly (wings of bat) | Constipation, abdominal and GI issues, swelling, cough |

| Tongue of dog | Houndstounge | Diarrhea, cough sedative, analgexic |

| Adder’s fork

|

Adder’s-tongues | Emetic and emollient, used on ulcers |

| Dogstooth violet | Emetic and emollient, used on ulcers | |

| Blind-worm’s sting

|

Poppies (blind eyes) | Pain relief, sedative, mood disorders |

| Wormwood (worms) | Bruises, loss of appetite, Gastritis and other stomach issues, fever, worm infestation | |

| Lizard’s leg | Ivy and other creeping plants | Headache, healing wounds, astringent, digestive problems, cough |

| Owlet’s wing | Unknown | |

| Scale of dragon

|

Tarragon | Appetite stimulant |

| Dragon’s Blood | Astringent | |

| Tooth of Wolf

|

Wolf’s bane | Stimulating, pain relief, inflammation |

| Club Moss | Diuretic, tonsillitis, wound healing | |

| Witches’ mummy | Mummia (parts of a mummy) | Used for all purposes |

| Maw of … sea shark | Unknown | |

| Root of Hemlock | Hemlock | Stiffness, inflammation, spasms, cramps |

| Liver of blaspheming Jew | Mugwort (Also known as “naughty man”) | Antimicrobial, GI problems, worm problems, sedative, epilepsy |

| Gall of Goat

|

Bezoar stone (stomach of goat) | Cure or counter poison |

| Honeysuckle | Laxative, induce sweating | |

| St. John’s Wort | Sleep disorders, mood disorders, depression and other mental health issues, diarrhea | |

| Slips of yew | Yew | Abortifacient, epilepsy, promotes menstruation |

| Nose of Turk | Unknown | |

| Tartar’s lips | Unknown | |

| Finger of birth-strangled bab

|

Bloodroot | Anti-microbial and anti-inflammatory |

| Cinquefoil | Pain, astringent, diarrhea, inflammation, healing wounds | |

| Tiger’s Chaudron | Lady’s Mantle | Astringent, diarrhea and GI orders, rashes and itching |

| Baboon’s blood | Blood of a spotted gecko | Regenerative |

End Notes

- “The Complete Works of William Shakespeare: Macbeth.” Act IV Scene 1. The Tech. Accessed March, 12, 2019. http://shakespeare.mit.edu/macbeth/index.html.

- Debra Ronca. “Is eye of newt a real thing.” com Published July 13, 2015. Accessed March, 12, 2019. https://people.howstuffworks.com/is-eye-of-newt-real-thing.htm.

- “Traditional medicine.” World Health Organization. Revised May 2003. Accessed March, 12, 2019. https://www.webcitation.org/5Zeyw2hfS?url=http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs134/en/

- The Greek Magical Papyri in Translation Including the Demotic Spells. ed. Hans Dieter Betz. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986), 167.

- Helen Thompson. “How Witches’ Brews Helped Bring Modern Drugs to Market” com October 31, 2014. Accessed March, 12, 2019, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/how-witches-brews-helped-bring-modern-drugs-market-180953202/.

- Amanda Mabillard. “The Historical Settings of Shakespeare’s Plays by Date.” Shakespeare Online. Published August 20, 2011. Accessed March, 12, 2019. http://www.shakespeare-online.com/keydates/chronologyofcontent2.html.

- W L Minkowski. “Women healers of the middle ages: selected aspects of their history.” American journal of public health 82 vol. 2 (February 1992): 288. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1694293/

- Ibid. 293.

- Helen Thompson. “How Witches’ Brews Helped Bring Modern Drugs to Market”

- The Greek Magical Papyri. ed. Hans Dieter Betz. 167.

- “Old Names For Herbs.” The Witches Sage. Published January 26, 2018. Accessed March, 12, 2019. https://thewitchessage.com/blogs/news/old-names-for-herbs.

- Roger M Grace. “Everthing You Ever Wanted to Know About Mustard Plasters.” REMINISCING Metropolitan News Enterprise. Metropolitan News Company. February 17, 2005. http://www.metnews.com/articles/2005/reminiscing021705.htm.

- PDR for Herbal Medicines. ed. Thomas Fleming, RPh. 2nd (Montvale: Medical Economics Company, Inc., 2000), 100.

- Scott Cunningham. Cunningham’s Encyclopedia of Magical Herbs. (St. Paul: Llewellyn Publications, 1985), 293.

- “Old Names For Herbs.” The Witches Sage.

- PDR for Herbal Medicines. ed. Thomas Fleming. 411.

- Ibid. 521.

- Scott Cunningham. Cunningham’s Encyclopedia of Magical Herbs. 290.

- PDR for Herbal Medicines. ed. Thomas Fleming. 609.

- Emily Miranker. “Found in the Eyes of Rams: The Bezoar and its Powers.” The New York Academy of Medicine Center for the History of Medicine and Public Health. Published December 2, 2016. Accessed March, 12, 2019. https://nyamcenterforhistory.org/2016/12/02/found-in-the-eyes-of-rams-the-bezoar-and-its-powers/.

- “Old Names For Herbs.” The Witches Sage.

- PDR for Herbal Medicines. ed. Thomas Fleming. 399.

- “Herbs at a Glance.” National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, US Department of Health & Human Services. Last Modified June 12, 2018. Accessed March, 12, 2019. https://nccih.nih.gov/health/herbsataglance.htm.

- PDR for Herbal Medicines. ed. Thomas Fleming. 720.

- Ibid. 842.

- Ibid. 387.

- The Greek Magical. ed. Hans Dieter Betz. 168.

- Scott Cunningham. Cunningham’s Encyclopedia of Magical Herbs. 304.

- Anne Van Arsdall. “Challenging the ‘Eye of Newt’ Image of Medieval Medicine” in The Medieval Hospital and Medical Practice. ed by Barbara S. Bowers. (Burlington: Ashgate Publishing Company, 2007), 195.

- Ibid. 197.

- Gregor Grass, Christopher Rensing, and Marc Solioz. “Metallic copper as an antimicrobial surface.” Applied and environmental microbiology 77 vol. 5 (December 30, 2011) 1541-1547. doi:10.1128/AEM.02766-10

- “Traditional medicine.” World Health Organization.

- Helen Thompson. “How Witches’ Brews Helped Bring Modern Drugs to Market.”

Bibliography

- Arsdall, Anne Van. “A New Translation of the Old English Herbarium” in Medieval Herbal Remedies: The Old English Herbarium and Anglo-Saxon Medicine. New York: Routledge, 2002.

- Arsdall, Anne Van. “Challenging the ‘Eye of Newt’ Image of Medieval Medicine” in The Medieval Hospital and Medical Practice. Edited by Barbara S. Bowers. Burlington: Ashgate Publishing Company, 2007.

- “Asian Water Plantain.” WebMD LLC. Accessed March, 12, 2019. https://www.webmd.com/vitamins/ai/ingredientmono-347/asian-water-plantain.

- Atanasova, Atanas G., Birgit Waltenberger, Eva-Maria Pferschy-Wenzig,Thomas Linder, Christoph Wawrosch, Pavel Uhrin, Veronika Temml, Limei Wang, Stefan Schwaiger, Elke H.Heiss, Judith M. Rollinger, Daniela Schuster, Johannes M. Breuss, Valery Bochkov, Marko D. Mihovilovic, Brigitte Kopp, Rudolf Bauer, Verena M.Dirsch, Hermann Stuppner “Discovery and resupply of pharmacologically active plant-derived natural products: A review.” Biotechnology Advances 33 vol. 8 (December 2015): 1582-1614. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biotechadv.2015.08.001.

- “The Complete Works of William Shakespeare: Macbeth.” The Tech. Accessed March, 12, 2019. http://shakespeare.mit.edu/macbeth/index.html.

- Cunningham, Scott. Cunningham’s Encyclopedia of Magical Herbs. St. Paul: Llewellyn Publications, 1985

- Cunningham, Scott. Magical Herbalism: The Secret Craft of the Wise. St. Paul: Llewellyn Publications, 1989.

- Douglas, Harper. “tarragon.” ETYMONLINE. Accessed March, 12, 2019. https://www.etymonline.com/word/tarragon

- “fenny.” Merriam-Webster. Accessed March, 12, 2019. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/fenny.

- Grace, Roger M. “Everthing You Ever Wanted to Know About Mustard Plasters.” REMINISCING Metropolitan News Enterprise. Metropolitan News Company. February 17, 2005. http://www.metnews.com/articles/2005/reminiscing021705.htm.

- Grass, Gregor, Christopher Rensing, and Marc Solioz. “Metallic copper as an antimicrobial surface.” Applied and environmental microbiology 77 vol. 5 (December 30, 2011) 1541-1547. doi:10.1128/AEM.02766-10

- The Greek Magical Papyri in Translation Including the Demotic Spells. Edited by Hans Dieter Betz. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986.

- “Herbs at a Glance.” National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, US Department of Health & Human Services. Last Modified June 12, 2018. Accessed March, 12, 2019. https://nccih.nih.gov/health/herbsataglance.htm.

- Kail, Tony M. Magico-Religious Groups and Ritualistic Activities: A Guide for First Responders. Boca Raton: Taylor & Francis Group, 2008.

- Mabillard, Amanda. “Macbeth Glossary: Chauldron.” Shakespeare Online. Published August 20, 2000. Accessed March, 12, 2019. http://www.shakespeare-online.com/plays/macbeth/macbethglossary/macbeth1_1/macbethglos_chaudron.html.

- Mabillard, Amanda. “Macbeth Glossary: Mummy.” Shakespeare Online. Published August 20, 2009. Accessed March, 12, 2019. http://www.shakespeare-online.com/plays/macbeth/macbethglossary/macbeth1_1/macbethglos_mummy.html.

- Mabillard, Amanda. “The Historical Settings of Shakespeare’s Plays by Date.” Shakespeare Online. Published August 20, 2011. Accessed March, 12, 2019. http://www.shakespeare-online.com/keydates/chronologyofcontent2.html.

- Minkowski, W L. “Women healers of the middle ages: selected aspects of their history.” American journal of public health 82 vol. 2 (February 1992): 288-95. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1694293/

- Miranker, Emily. “Found in the Eyes of Rams: The Bezoar and its Powers.” The New York Academy of Medicine Center for the History of Medicine and Public Health. Published December 2, 2016. Accessed March, 12, 2019. https://nyamcenterforhistory.org/2016/12/02/found-in-the-eyes-of-rams-the-bezoar-and-its-powers/.

- Müller, Jürgen. “Love Potions and the Ointment of Witches: Historical Aspects of the Nightshade Alkaloids.” Journal of toxicology. Clinical toxicology. 36, vol. 3 (February 1998): 617-627. DOI: 10.3109/15563659809028060

- “Old Names For Herbs.” The Witches Sage. Published January 26, 2018. Accessed March, 12, 2019. https://thewitchessage.com/blogs/news/old-names-for-herbs.

- PDR for Herbal Medicines. Chief Editor Thomas Fleming, RPh. 2nd ed. Montvale: Medical Economics Company, Inc., 2000.

- Ronca, Debra. “Is eye of newt a real thing.” HowStuffWorks.com. Published July 13 ,2015. Accessed March, 12, 2019. URL.

- Thompson, Helen. “How Witches’ Brews Helped Bring Modern Drugs to Market” Smithsonian.com October 31, 2014. Accessed March, 12, 2019. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/how-witches-brews-helped-bring-modern-drugs-market-180953202/.

- “Traditional medicine.” World Health Organization. Revised May 2003. Accessed March, 12, 2019. https://www.webcitation.org/5Zeyw2hfS?url=http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs134/en/.

MARIEL TISHMA currently serves as an Executive Editorial Assistant with Hektoen International. She’s been published in Hektoen International, Argot Magazine, Syntax and Salt, The Artifice, and Fickle Muses. She graduated from Columbia College Chicago with a BA in creative writing and a minor in biology. Learn more at marieltishma.com.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 11, Issue 4 – Fall 2019

Spring 2019 | Sections | Literary Essays

Leave a Reply