Jamie Samson

Dublin, Ireland

|

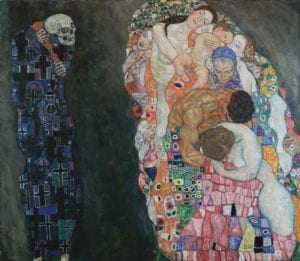

| Death and life by Gustav Klimt. The radical “otherness” of death is a fixture of art history, as illustrated here in Klimt’s ‘Death and Life’. 1915. Leopold Museum, Vienna |

“Everyone who is born,” Susan Sontag wrote in Illness as Metaphor, “holds dual citizenship, in the kingdom of the well and in the kingdom of the sick.”1 While the passport denoting health and vigor might get us through customs most of the time, we eventually reach that unwelcome day when it is grimly necessary to “identify ourselves as citizens of that other place.”2

When it came to surveying and mapping “that other place,” Sontag knew whereof she spoke. Throughout an extraordinary literary life, she had the dreaded word “cancer” stamped into her shadow passport not once but three times, becoming, by her final years, something of a veteran correspondent from the frontlines of the condition. As one might expect from a wounded survivor, the reports she filed grew more jaded and pessimistic and morosely witty with each trip until – in 2004 and at the age of seventy-one – she disappeared for good over its horizon.

The notion of illness as a foreign land, with its strangely dressed inhabitants and forbidding local languages, has been a central one in modern literature. Virginia Woolf, for instance, wrote in “On Being Ill” of the “undiscovered countries” that are suddenly revealed when “the lights of health go down.” And the metaphor has continued to gain currency in the decades since Sontag published her essay. Another great American scribe, Christopher Hitchens, envisioned his passage out of the pastureland of health, flanked by carers and paramedics and physicians, as a kind of deportation, “taking me from the country of the well across the stark frontier that marks off the land of malady.”3 Like Sontag, Hitchens in his time had seen quite a few conflict zones and more than once had experienced the unique thrill of the near-death experience.4 And like Sontag, he refuted the oft-repeated cliché that the cancer patient is entangled in some kind of “battle” (a cliché that even this writer admittedly fell victim to in the preceding paragraph, with all that business about “frontlines”). Describing the effects of chemotherapy on his body and mind, Hitchens painted a picture of almost unbearable enervation and vulnerability:

Allow me to inform you, though, that when you sit in a room with a set of other finalists, and kindly people bring a huge transparent bag of poison and plug it into your arm, and you either read or don’t read a book while the venom sack gradually empties itself into your system, the image of the ardent soldier is the very last one that will occur to you. You feel swamped with passivity and impotence: dissolving in powerlessness like a sugar lump in water.5

Perhaps the most beautiful fictional account of this expatriation to the land of “passivity and impotence” can be found in John Updike’s short story “The City,”6 collected in his 1987 book Trust Me. The story follows a sales representative named Carson, who makes a business trip to some unfamiliar city while harboring an intense abdominal pain. (Once again, the theme of sickness-as-travel is immediately touched upon). At first, Carson blames his unwholesome airline breakfast – peanuts washed down with a sub-par old-fashioned – for the freshly aching gut. Soon, however, he realizes that things are a little more grave than that. He cancels his business meetings and retires to his hotel room where he rolls around on the bathroom floor for quite some time before finally taking a taxi to the nearest clinic. His relocation to the Other Kingdom is almost complete, but first he must face another grim phenomenon known to customs agents and hospital administrators alike – the spectre of bureaucracy.

Carson expected to surrender the burden of his body utterly, but instead found himself obliged to carry it through a series of fresh efforts — forms to be filled out, proofs to be supplied of his financial fitness to be ill, a series of waits to be endured, on crowded benches and padded chairs…7

Carson is eventually treated for appendicitis, and undergoes surgery. He spends the next five days convalescing, with a “sore abdomen and clearer head.” Previously dour and career-obsessed, he is suddenly overwhelmed by a childlike love of existence. The alien world of the hospital bequeaths to him an intense love of ordinary life, so that even a relatively mundane view strikes him with spiritual force: “A quarter-moon leaned small and cold in the sky above the glowing square windows of another wing of the hospital, and his position in the world and the universe seemed clear enough.”

It is a gorgeous moment, an epiphany in the purest sense, and it reminds us that we cannot focus solely on trips to the Other Kingdom that are strictly one-way. We must also take a look at what it is like to return, to reclaim that original passport. Like Updike’s protagonist, those who have learned the ways of illness, endured its climate, used its currency, and mastered its language, often come home to the world of the well with the most intense feelings of happiness. “I am gleaming with survivorship,” Sontag wrote giddily, after her first recovery.

A similar sense of paradise regained pervades the later work of Patrick Kavanagh, the eminent Irish poet. Following a diagnosis of lung cancer, Kavanagh spent several months in a draughty Dublin hospital, where he underwent life-threatening surgery. Upon readmission to the outside world, he possessed one less lung but, as if to make up for it, an entirely new outlook. The experience proved genuinely transformative, ridding him of his former bitterness and anxiety and reframing his existence in terms of quotidian love. In a poem entitled “The Hospital,” he states things plainly:

A year ago I fell in love with the functional ward

Of a chest hospital.8

Kavanagh goes on to credit his ordeal with teaching him to “snatch out of time the passionate transitory” – a phrase that captures the restorative spirit of the pieces by Sontag and Woolf, Hitchens and Updike, in a single piercing flash.

It might be that the world is pure randomness and abject chaos, and that all health is on loan, all light in debt to the dark, but nonetheless we continue to lay our little gardens of meaning onto the harsh soil of life. There is little we can do about it; we are flower-loving creatures. The Other Kingdom, of course, may summon us at any time, and hold us within its borders indefinitely, but sometimes we will get to come home, newly in love with the “passionate transitory” and gleaming with survivorship.

References:

- Sontag, Susan, “Illness as Metaphor.” The New York Review of Books (26/1/1978)

- Ibid.

- Hitchens, Christopher. “Topic of Cancer.” Vanity Fair (4/8/2010)

- The Guardian (19/2/2009) (https://www.theguardian.com/media/2009/feb/19/christopher-hitchens-beirut-attack)

- Hitchens, Christopher. Mortality. New York: Atlantic Books (2012)

- Updike, John. Trust Me. New York: Alfred A. Knopf (1987)

- Ibid.

- Kavanagh, Patrick. Collected Poems. London: Penguin (1964)

JAMIE SAMSON is a freelance writer from Dublin, Ireland. Jamie has been published in The Irish Times, Headstuff, Metro Eireann, and BookBrowse. He won the Kanturk Flash Fiction Prize in 2018, and was nominated for the Hennessy Literary Awards in the same year.

Spring 2019 | Sections | Literary Essays

Leave a Reply