Hayat El Boukari

Tetouan, Morocco

|

|

|

|

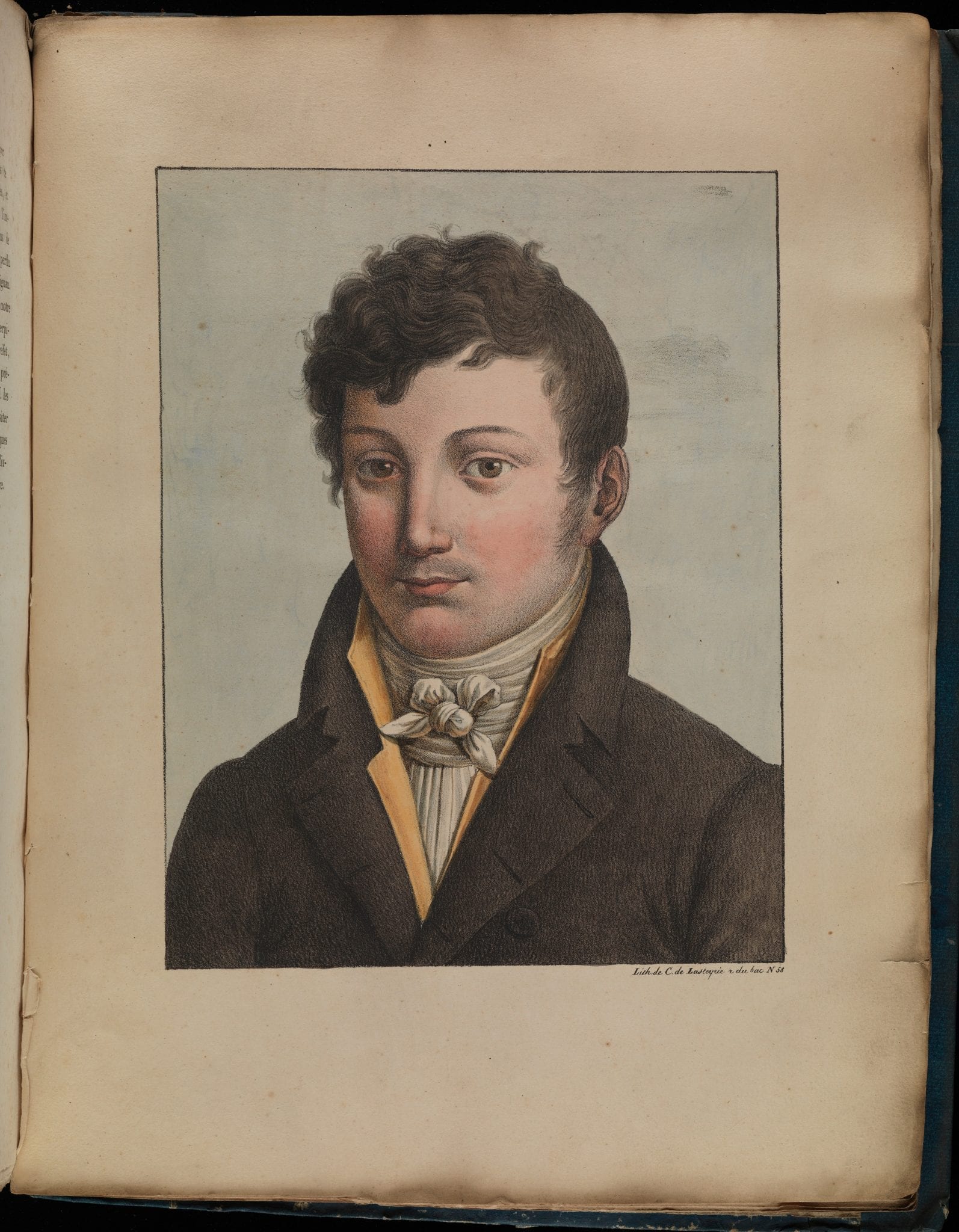

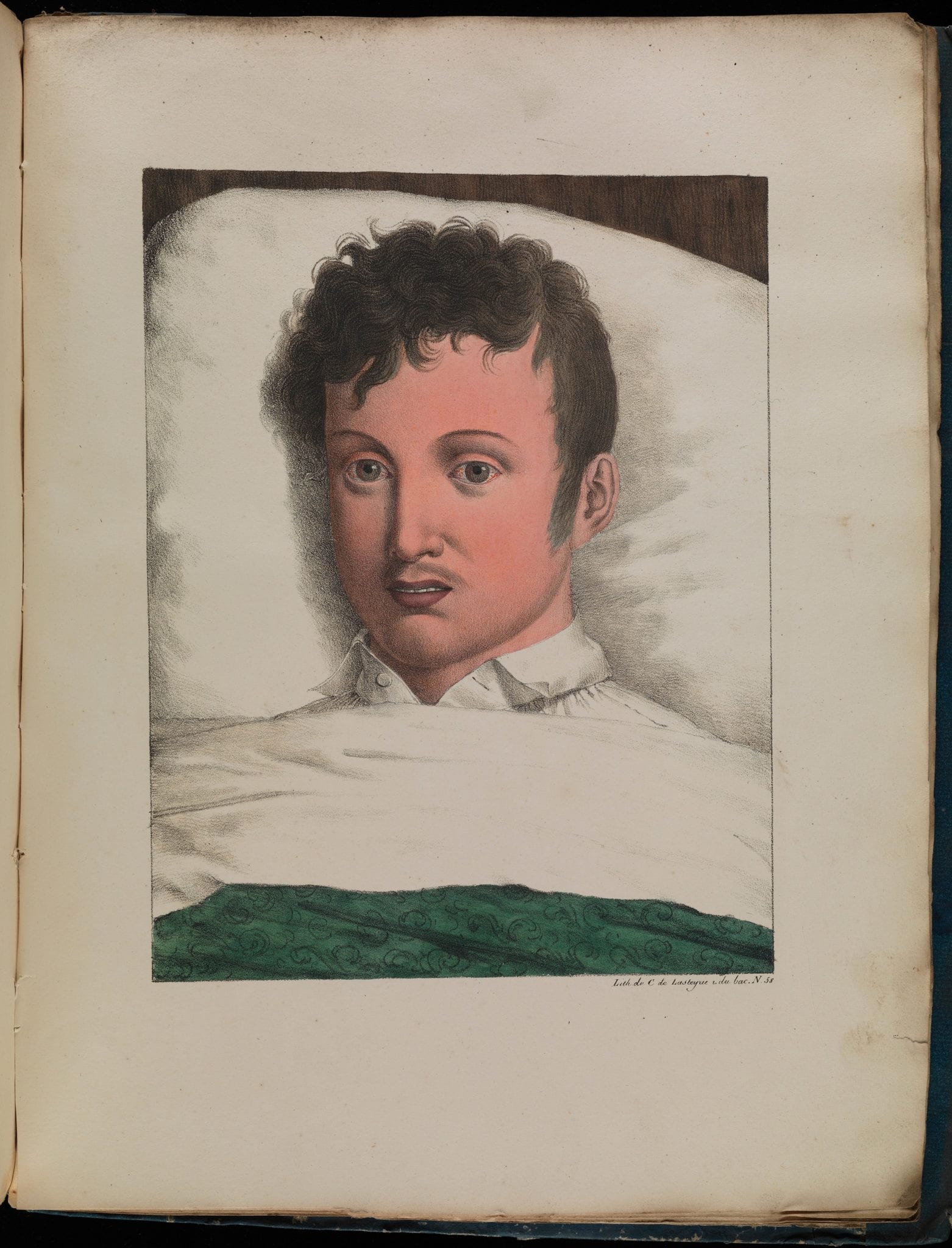

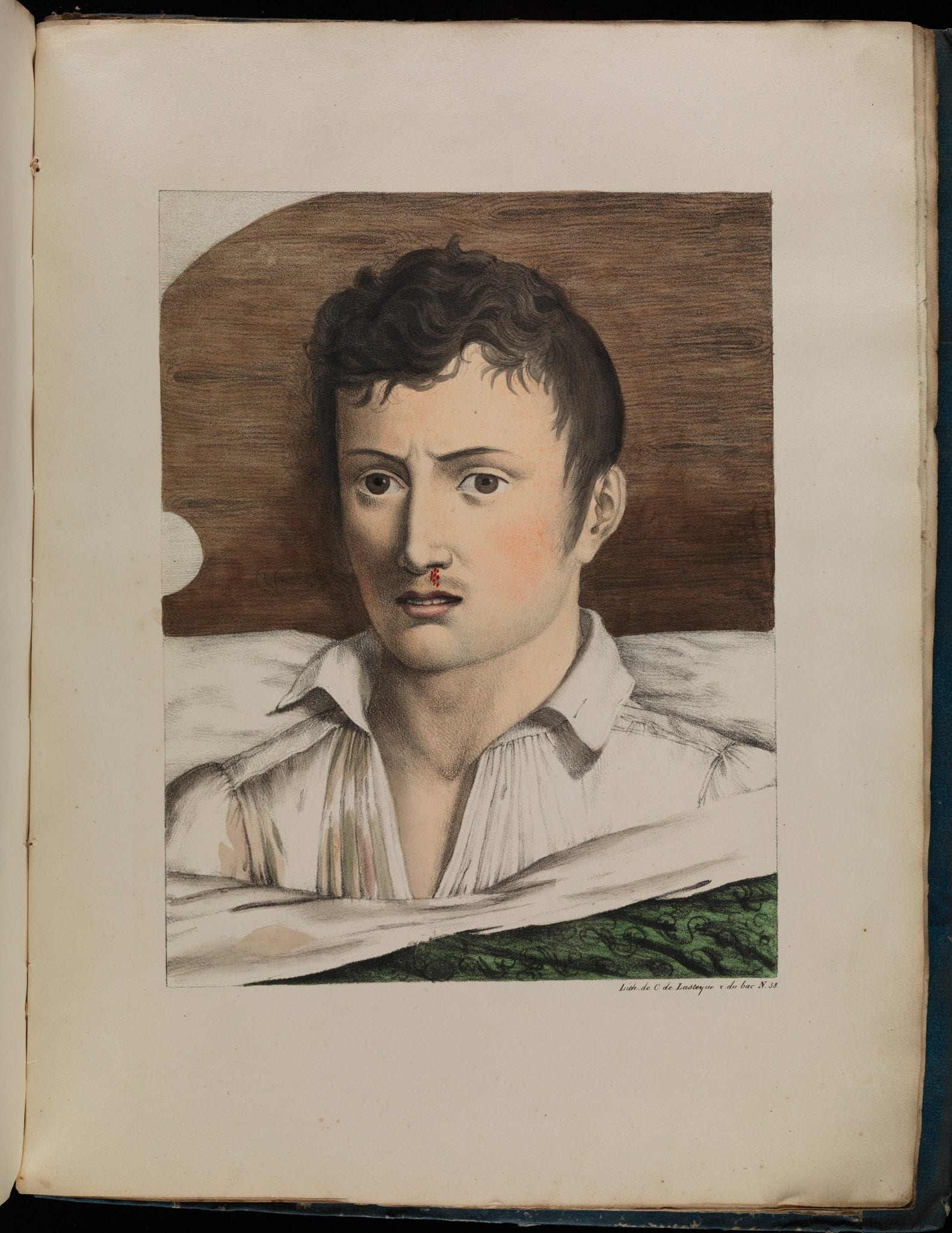

| Four plates showing the development of yellow fever. From the title: Observations sur la fièvre jaune, faites à Cadix, en 1819 / par MM. Pariset et Mazet. Authors: Etienne Pariset (1770-1847) and André Mazet (1793-1821). Wellcome Collection. Public domain. | |||

|

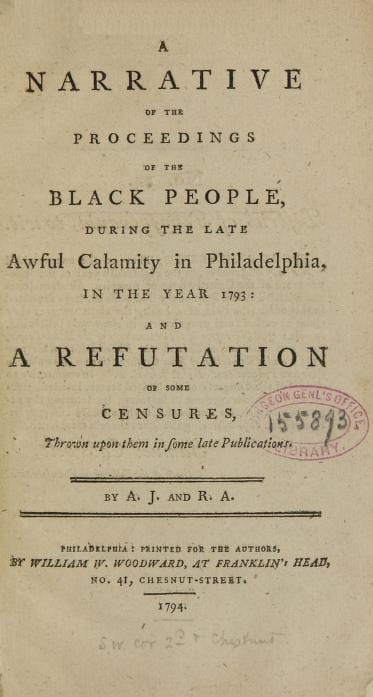

| “A narrative of the proceedings of the black people, during the late awful calamity in Philadelphia,” by Jones, Absalom, Allen, Richard, Clarkson, Matthew, Woodward, William Wallis, printer. Internet Archive. |

On August 3, 1793, a young French sailor rooming at Richard Denney’s boarding house was desperately ill with a fever.1 As he was a poor foreigner, no one bothered to find out his name. His fever worsening, he died a few days later, as also did eight residents from two houses in the same street . . . but the city did not take notice as the killer was already moving through the streets of the city.1 On Monday August 19 a thirty-three-year old Catherine was also dying, gasping and groaning and vomiting foul black bile.1 The two neighborhood doctors caring for her did what they could. They gave her cool drinks of barley water and apple water to reduce the fever, and red wine with laudanum to help her rest, but nothing worked, and her condition worsened.1 In desperation the two physicians sent for Dr. Benjamin Rush, a highly respected physician who in recent days had seen an unusual number of patients with similar symptoms.1

All three doctors recounted the symptoms they had seen: chills, headache, and a painful aching in the back, arms, and legs, a high fever, a sudden remission, then the fever would shoot up again, the patient would become jaundiced and began to bleed from all over, and soon die.1 Dr. Rush also observed tiny reddish eruptions on the skin (petechiae), reminding him of a sickness that had swept through Philadelphia back in 1762, so he boldly announced that the disease they now confronted was the dreaded yellow fever, a deadly plague that carried a fifty percent mortality.1

It all had started in 1792, when the Hankey and two other ships carried nearly three hundred idealistic antislavery British radicals to Bolama, an island off the coast of West Africa. They hoped to establish a colony designed to undermine the Atlantic slave trade by hiring rather than enslaving Africans.4 Most of these colonists eventually died from a particularly violent strain of yellow fever and the survivors, attempting to return to Britain and fearing interception by hostile French chips, ended up in Grenada.3, 4 From there they spread the disease throughout the West Indies,4 and by July 1793 to Philadelphia, then the nation’s capital.3 There the yellow fever killed five thousand people, forcing tens of thousands of residents, including George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and other prominent federal government leaders, to flee to Washington and move the US capital there.4

Among those who stepped forward to aid people and save the city were members of the newly emerging community of free African Americans.4 Led by Absalom Jones, Richard Allen, and Anne Saville, black Philadelphians volunteered to nurse the sick and bury the dead—both dangerous undertakings at the time.4 Many African Americans and physicians exposed to the yellow-fever infected mosquitoes died in disproportionately high numbers.4 When a newspaper editor later maligned black people for their efforts, Jones and Allen wrote a vigorous response—among the first publications by African Americans in the new nation.4

During the ensuing decade, epidemics of yellow fever occurred each year throughout the Americas.4 Among other consequences, the epidemics helped solidify the decision of the leaders of the new nation to move the capital to Washington D.C and away epidemic prone Philadelphia.3, 4

References:

- Murphy, Jim. An American Plague: The True and Terrifying Story of the Yellow Fever Epidemic of 1793 . New York: Clarion Books, 2003.

- Crosby, Molly Caldwell. The American Plague: The Untold Story of Yellow Fever the Epidemic That Shaped Our History. New York: Penguin, 2007.

- Smith, Billy G. Ship of Death: The Voyage That Changed the Atlantic World. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013.

- Nyam, History. “The First Yellow Fever Pandemic: Slavery and Its Consequences.” Books, Health and History the New York academy of medicine, October 15, 2018. https://nyamcenterforhistory.org/2018/10/15/yellow-fever-pandemic/.

HAYAT EL BOUKARI, MD, is a general practitioner who graduated from the Faculty of Medicine of Rabat in Morocco in 2017. Hayat was born and raised in the north of Morocco and is passionate about medicine and interested in exploring its history and art.

Winter 2020 | Sections | Infectious Diseases

Leave a Reply