Cross De Idialu

Port Harcourt, Nigeria

|

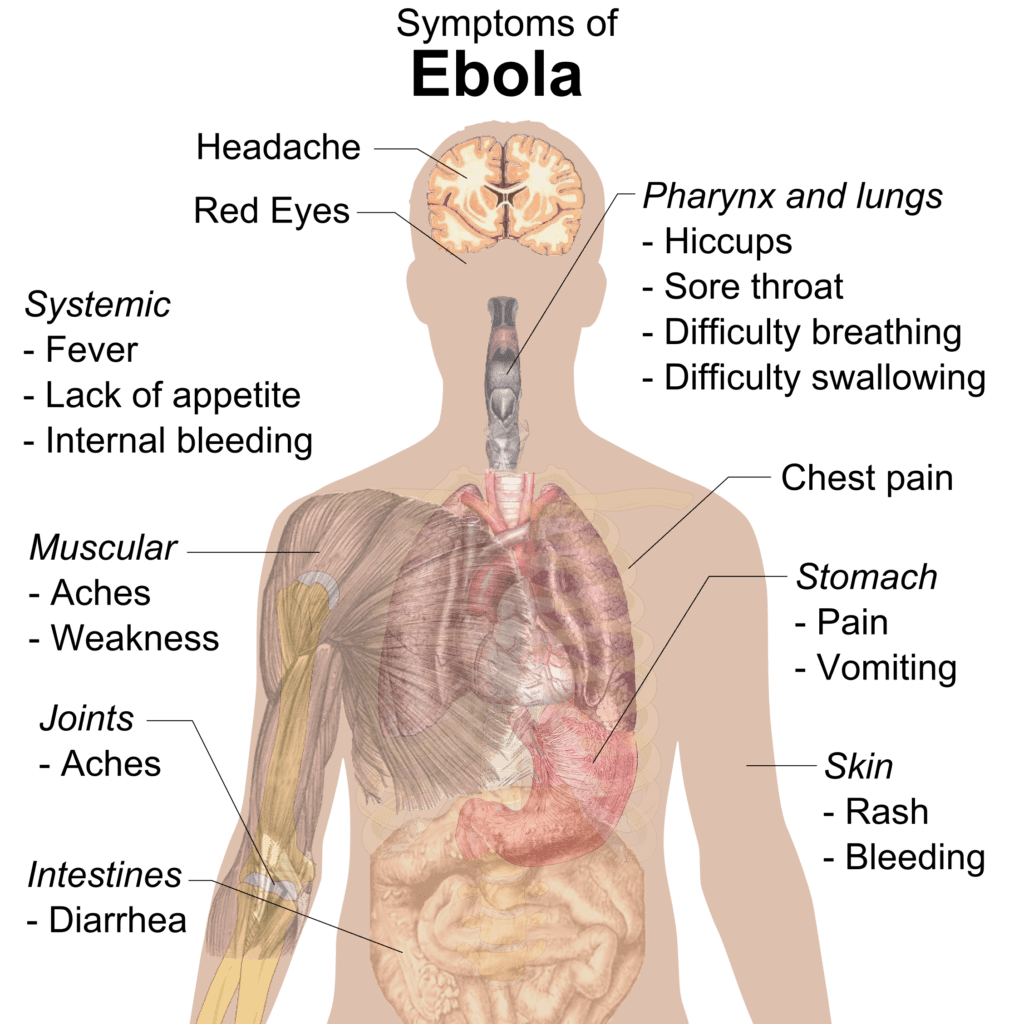

| Symptoms of Ebola. Illustration by Mikael Häggström. August 2, 2014. by Mikael Häggström. August 2, 2014. Public Domain, |

It was the year 2014, and an unknown deadly disease was eating deep into the western region of the African continent. The first case was said to have occurred on December 26, 2013 when a little boy who most likely had contact with wild animals fell ill and died two days later. His sickness had been characterized by fever, diarrhea, and vomiting.1 It was believed he had been infected by bats, because he had been playing close to a bat-infested hollow tree.2 In the following weeks, family members and relatives who had contact with the boy and his immediate family also fell ill and died.

On January 24, 2014 the first official medical alert was raised about this unknown disease. A few months later, on March 21, 2014, the Institut Pasteur in Lyon, France confirmed that the causative agent was a filovirus that was causing either Ebola disease or Marburg hemorrhagic fever.3 In March of that same year, the World Health Organization (WHO) made an official announcement on its website, and on August 8, 2014 WHO stated that the worsening conditions in West Africa were a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) that posed risk on an international level. Ebola virus disease (EVD) has a high mortality rate that ranges between 25- 90%.4 The first case on record occurred in the Democratic Republic of Congo (then known as Zaire) in 1976.

Sunday, July 20, 2014 began like any other day at First Consultants Medical Centre (FCMC) in Lagos, Nigeria. A Liberian-American lawyer, Patrick Sawyer, had boarded a plane from Liberia to Nigeria for a conference, which should never have happened because he had been in close contact his sister, who had died of the disease. He collapsed at the airport in Nigeria and was rushed to FCMC to ascertain what was wrong. At the time, medical doctors were on strike all over Nigeria or he would have been taken to a government facility, but as a result of the strike he was taken to FCMC. The first physician who saw him diagnosed malaria, and it was not until the next day, when Dr. Stella Adadevoh was making her rounds, that she correctly diagnosed the illness as Ebola.

|

|

A portrait of Dr. Stella Adadevoh |

Mr. Sawyer had been asked if he had come in contact with anyone with Ebola, but he lied and said he had not. Being a thorough professional, Dr. Adadevoh contacted the Federal Ministry of Health as well as its counterpart in Lagos. She then proceeded to send samples for further tests. But while in the hospital waiting for the test results, Mr. Sawyer became agitated and asked to leave. The medical team strongly objected, but the Liberian ambassador to Nigeria exerted pressure by calling Dr. Adadevoh and informing her that she could be charged for kidnapping and holding one of their citizens against his free will.

“He was screaming. He pulled his intravenous [tubes] and spilled the blood everywhere,” said Dr. Benjamin Ohiaeri, director of FCMC.5 But none of the hospital staff budged; they had total faith in Dr. Adadevoh’s judgment. Mr. Sawyer was later confirmed to have been infected as suspected, and he died five days later. Unfortunately for Dr. Adadevoh and her team, eleven of them became infected with the virus. A medical center better equipped to care for infected patients was quickly set up, but out of the eleven, five – including Dr. Adadevoh – paid the ultimate price with their lives, doing what they had solemnly sworn to do.

Dr. Stella A. Adadevoh (1956-2014) was born in Lagos, Nigeria and had her high school education at Queens School, Ibadan, after which she studied medicine at the University of Lagos. On completing her internship and residency at the Lagos University Teaching Hospital, she moved to the United Kingdom for a fellowship in endocrinology at Hammersmith Hospital. On returning, she got a job with First Consultants Medical Centre (FCMC), where she served until her death in 2014. She was the great-granddaughter of Herbert Macaulay, one of the founding fathers of Nigeria as we know it today. His image appears on the one naira coin. Dr. Nnamdi Azikwe, who was the first president of Nigeria, was her great-uncle. Previously, in 2012, during an outbreak of swine flu (H1N1) in Nigeria, she had been the first to recognize the disease and alert the health authorities about the dangers it posed.6

|

|

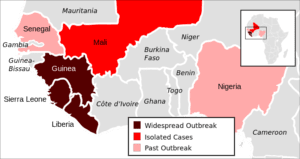

2014 Ebola virus epidemic in West Africa. Illustration by ZeLonewolf. |

By identifying the index patient, Dr. Adadevoh effectively ensured that the spread of Ebola could be contained. This is even more impressive because Ebola had never been diagnosed in Nigeria before, so she had no prior experience with the disease.

During the Ebola crisis,11 325 people lost their lives between 2014 and 2016.7 Out of these, only eight were from or in Nigeria.8 To put this into perspective, there were 1597 deaths from all previously known cases of Ebola.9 On October 20, 2014 the World Health Organization (WHO) declared Nigeria Ebola-free.10

Ebola eventually spread to more countries outside of Africa.11 The United States Center for Disease Control and Prevention (US-CDC) sent researchers to Nigeria to study how the country was able to effectively manage the virus.12

In a country that is slow in responding to challenges and where many basic procedures are made to seem herculean, this was one of those rare cases where the system triumphed and a nation was saved – primarily because of the bravery of one woman who put humanity before her own safety. The Nigerian response to Ebola showed what can be achieved when people come together around a shared goal. The crisis also demonstrated how fragile we are, and that humanity still has many battles to face.

References

- WHO. https://www.who.int/csr/disease/ebola/one-year-report/virus-origin/en/. Accessed April 12, 2019.

- CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/history/2014-2016-outbreak/index.html. Accessed April 13, 2019.

- Institut Pasteur. https://www.pasteur.fr/en/research-journal/reports/ebola-2013-2016-lessons-learned-and-how-respond-new-epidemics. Accessed April 15, 2019.

- National Center for Biotechnology Information. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5349256/. Accessed April 12, 2019.

- BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-29696011. Accessed April 15, 2019

- Development Report. https://developmentreport.ng/dr-adadevoh-ebola-victim-gets-lawmakers-attention/. Accessed April 13, 2019.

- CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/history/2014-2016-outbreak/index.html. Accessed April 15, 2019

- CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/history/2014-2016-outbreak/index.html. Accessed April 14, 2019

- CDC. Outbreaks Chronology: Ebola Virus Disease. Accessed April 15, 2019

- WHO. https://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/statements/2014/nigeria-ends-ebola/en/. accessed April 15, 2019

- CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/history/2014-2016-outbreak/index.html. Accessed April 14, 2019.

- Huffington Post. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/nigeria-contains-ebola-outbreak_n_5959442. Accessed April 15, 2019

CROSS DE IDIALU is a management consultant who writes about topics that cut across diverse sectors and industries. His writings reflect the plight of the voiceless, especially in developing countries.

Spring 2019 | Sections | Infectious Diseases

Leave a Reply