Yvonne Kusiima

Kampala, Uganda

|

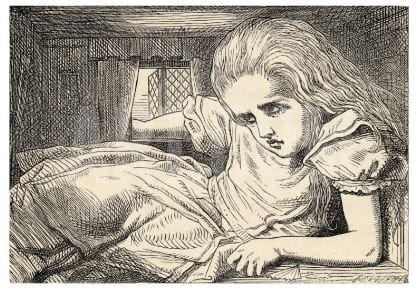

| Alice experiences total-body macrosomatogonosia. Illustration by John Tenniel (1865) |

In 1865 the world was introduced to the novel Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, written by English author Charles Lutwidge Dodgson under the pseudonym Lewis Carroll. In the book, a young girl named Alice is feeling bored and drowsy while sitting on the riverbank with her elder sister when she notices a talking, clothed White Rabbit with a pocket watch run past. She follows it down a rabbit hole when suddenly she falls a long way to a curious hall with many locked doors of all sizes. She finds a small key to a door too small for her to fit through, but through it she sees an attractive garden. She then discovers a bottle on a table labeled “DRINK ME,” the contents of which cause her to shrink too small to reach the key she has left on the table. She eats a cake with “EAT ME” written on it as the first chapter closes. In the next chapter, she grows to such a tremendous size that her head hits the ceiling, then shrinks down once again.1

The perception of shrinking and tremendous growth are symptoms of Alice in Wonderland Syndrome. The first person to use this term was Dr. John Todd, a British consultant psychiatrist at High Royds Hospital at Menston in West Yorkshire.2 Like Alice, patients may experience either micropsia or macropsia. Micropsia is an abnormal visual condition, usually occurring in the context of visual hallucination, in which the person sees objects as being smaller than they are in reality.3 Macropsia is a condition where the individual sees everything larger than it actually is.4

People with Alice in Wonderland Syndrome may experience hallucinations or illusions of expansion, reduction, or distortion of their own body image, such as microsomatognosia (feeling that their own body or body parts are shrinking), or macrosomatognosia (feeling that their own body or body parts are growing taller or larger).5 Alice in Wonderland Syndrome affects vision, sensation, touch, and hearing, as well as one’s own body image.6

Patients with Alice in Wonderland Syndrome usually suffer from migraines, although their role is still not well understood. Both vascular and electrical theories have been suggested. For example, visual distortions may be a result of transient, localized restriction in blood supply to areas of the visual pathway during migraine attacks.5

There is evidence from his diaries that Lewis Carroll suffered from migraines. He often reported a “bilious headache” with severe vomiting, and in 1885 wrote that he experienced “for the second time that odd optical affection of seeing moving fortifications, followed by a headache.” In 1858 Carroll consulted an eminent ophthalmologist, William Bowman, about a visual disturbance in his right eye. Bowman did not seem to think that anything could be done to remedy Carroll’s eye condition but advised him “not to read long at a time, nor at the railway, and to keep large type by candlelight.”7

The nature of Bowman’s medical advice suggests he suspected a functional disturbance due to eye strain from reading an excessive amount or under adverse conditions. Bowman might have failed to achieve a more accurate diagnosis for Carroll’s visual problem because before the 1870’s, the visual manifestations of migraine were not widely recognized.8

It has been said, “Alice trod the path of a wonderland well known to her creator.”2 The exhaustive descriptions of metamorphosis in Carroll’s novel were the first to portray the bodily distortions characteristic of Alice in Wonderland Syndrome.9 Complete and partial forms of the syndrome occur in many disorders such as epilepsy, infectious states, and fever.5 Carroll may have suffered from temporal lobe epilepsy, which is the most common form of epilepsy with focal seizures.10 Carroll had at least one incident where he lost consciousness and woke with a bloody nose, which he recorded in his diary and mentioned that the occurrence left him not feeling himself for “quite sometime afterward.” This attack was diagnosed as possibly “epileptiform” and Carroll wrote about his “seizures” in the same diary.11

Without question, Carroll possessed a brilliant mind. There are societies in many parts of the world dedicated to the enjoyment and promotion of his works and the investigation of his life.12 More than a century and a half later, the world continues to be fascinated by Carroll’s Wonderland. Illness and art have always been bound, especially when neurological and psychiatric diseases are involved.13 In naming Alice in Wonderland Syndrome after Carroll’s work, which has been translated into several languages, Todd brought to attention the idea that Carroll might have simply been taking the reader for an adventure in his own mind. Perhaps many people with Alice in Wonderland Syndrome around the world are now able to put a name to their condition, something that was not possible for Carroll.

End notes

- L. Carroll, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Macmillan, London, UK, 1865.

- J. Todd, “The syndrome of Alice in Wonderland,” Canadian Medical Association Journal, vol. 73, no. 9, 701-704, 1955.

- “Micropsia”. Mosby’s Emergency Dictionary. Philadelphia: Elsevier Health Sciences. 1998.

- “Macropsia”. Collins English Dictionary. London: Collins English Dictionary. London: Collins. 2000. ISBN 978-0-00-752274-3.

- Farooq O, Fine E J (December 2017). “Alice in Wonderland Syndrome: A Historical andMedical Review”. Pediatric Neurology. 77:5-11.

- Stapinski H (23 June 2014). “I Had Alice in Wonderland Syndrome”. The New York Times.

- R.L. Green, The Diaries of Lewis Carroll, Cassell &Co, London, UK, 1953.

- K. Podoll and D. Robinson, “Lewis Carroll’s migraine experiences [10],” Lancet, vol. 353, no. 9161, 1366, 1999.

- Martin R. “Through the Looking Glass, Another Look at Migraine” (PDF)

- Angier N (1993-10-12). In the Temporal Lobes, Seizures and Creativity”. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331.

- Woolf, Jenny (4 February 2010). The Mystery of Lewis Carroll. St. Martin’s Press. 298-9. ISBN 978-0-312-67371-0.

- “Lewis Carroll Societies”. Lewiscarrollsociety.org.uk. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- E.F.M. Wijdicks, Neurocinema: When Film Meets Neurology Taylor & Francis Group, 2015.

YVONNE KUSIIMA is a social scientist who holds a degree of Bachelor of Arts in Social Sciences from Kyambogo University. Yvonne studied Social Administration, Sociology and Psychology. In addition, Yvonne holds a diploma in Computer Science and Information Technology from Nkozi University. Yvonne is also a freelance writer who loves creative writing.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 12, Issue 1 – Winter 2020

Leave a Reply