Jennifer Borst

Hammonds Plains, Nova Scotia

As a bleary-eyed new parent, I found myself embracing the quiescence and prolonged slumber swaddling offered my restless and sleepless first-born. Strategic bundling subsequently proved disappointingly ineffective with my second colicky child and unnecessary with my jovial, naturally sleepy third. While the question to swaddle or not no longer applies to my own brood, it continues to arise in my clinical practice and within the broader public discourse around safe child care practices.

Most modern-day adoptees of swaddling are likely unaware of its lengthy and controversial history. Swaddling was widely practiced in the Western world until it fell out of favor a couple of centuries ago. Following a sharp decline during the eighteenth century, swaddling is seeing a resurgence in the West. While advances in science over the past century have introduced new insights into the swaddling debate, common historical themes and controversy persist around this age-old custom.

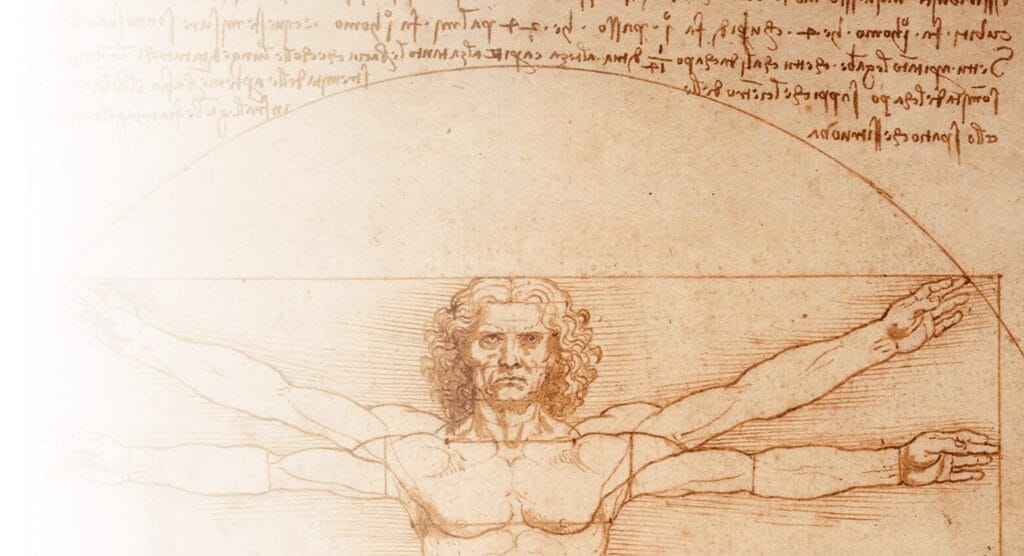

Swaddling has been practiced for thousands of years, possibly originating in Central Asia in 4000 BC and spreading through nomadic trading to Eurasia.1 Artwork from Cyprus and Crete, along with votive offerings of swaddled infants during antiquity, support its ancient origins.2 Although swaddling in the contemporary sense conjures images of happily bundled babies, traditional swaddling techniques were, in fact, markedly more restrictive than their present-day form. Classic swaddling used strips of cloth tightly wrapped around the infant’s body from head to foot, with the intention to keep the body immobilized.3 Other methods of swaddling have included the use of a cradleboard or cradle, which involves strapping or tying infants to a solid base or cradle.4 While modern-day swaddling is typically less severe, tight prolonged swaddling is still in use today, especially by indigenous groups.5

During antiquity, swaddling was seen as a necessary practice, intended to shape infants who were perceived as lacking form, weak, and imperfect.6 In the Middle Ages fear and superstition prevailed, with infants regarded as vulnerable to evil but also potentially dangerous to others. In some cases, infants were swaddled, placed in baskets, and pulled into trees as a means of protecting the baby and those around him.7 By modern times, swaddling was described as a way to keep babies warm.8 In nineteenth century Russia and twentieth century Bulgaria and Poland, preventing self-inflicted harm (e.g., poking eyes, masturbation) arose as a justification for swaddling.9 Likely throughout the ages, swaddling has been used to pacify infants and keep them immobilized as a means to ease the burden of caregivers and ensure infant safety during transport and while caregivers worked.10 Upon reaching the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, the calming and sleep-inducing effects of swaddling became the predominant rationale for snuggly wrapped infants.11

Following millennia of largely unquestioned adherence, opposition to swaddling took root in the medical and philosophical communities, starting in the sixteenth century.12 By the late eighteenth century, swaddling saw a dramatic decline in the West, particularly in its stringent forms.13 A number of factors likely account for this shift and include: increasing awareness of the potential physical, developmental, and psychological harm from swaddling; increasing recognition of children’s subjective experience; and prevailing ideas of liberty and emancipation.14

Felix Würtz (c. 1500–c. 1598), a Swiss surgeon of the sixteenth century, was one of the first to publicly criticize swaddling rather than simply describe the millennia-old practice.15 In his Children’s Book, published posthumously in 1612 and later translated into English in 1656, Würtz provided a new perspective on swaddling.16 His account was groundbreaking in two ways: it brought the child’s subjective experience to the forefront and it identified the potential for tight swaddling to cause physical harm.17 Following in Würtz’s footsteps, other members of the medical community also began to voice their concern about the dangers of swaddling. This included French surgeon Jacques Guillemeau (1550–1613), whose account of swaddling-induced orthopedic problems heralded future concerns about hip dysplasia.18 The eighteenth century British physician William Cadogan (1711–1797) was likely the first to call for an end to swaddling practices, rather than reform them.19 In his “Essay upon Nursing” published in 1748, Cadogan described the physical restrictions imposed by swaddling and called for “the free use of the limbs.”20

Philosophers such as British John Locke (1632–1704), Swiss-born Jean Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778), and German Immanuel Kant (1742–1803) echoed physicians’ concerns and also called for the abolition of swaddling.21 Contemporary German psychologist Ralph Frenken connects Rousseau’s rejection of swaddling with the philosopher’s infamous quote: “Man is born free, and everywhere he is in chains.”22 As per Frenken, “Swaddling becomes with Rousseau the prototypical suppression of man by man.”23

By the late eighteenth century, swaddling was no longer commonly practiced by the urban upper class and elites. The lower classes and rural areas later followed suit, albeit with residual pockets of swaddling persisting throughout Europe.24 After losing favor in the West during the eighteenth century, swaddling has since regained popularity in some countries including the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Netherlands.25 Contemporary swaddling is typically less tightly applied, especially around the lower extremities, and often involves the use of a single blanket or premade winged suit.26 Swaddling remains controversial, with ongoing concerns about its potential adverse physical, developmental, and psychological effects.27

Harvey Karp, an American pediatrician, is one of the most recognized contemporary proponents of swaddling. Karp claims that newborns are born “immature,” an evolutionary compromise allowing for a large brain to be birthed through the maternal pelvis.28 He also suggests that neonates are born with a “calming reflex,” an automatic process that can be selectively turned on or off by mimicking the intrauterine environment. According to Karp, swaddling is one of the five key ways to induce the “calming reflex.”29 Quoting Karp directly: “Remember—your baby’s brain was so big that you had to ‘evict’ her after nine months, even though she was still smushy, mushy and very immature. As a result, she isn’t quite ready for the big, bad outside world” (emphasis added).30 Pertaining to swaddling, Karp writes: “The womb kept your precious little one wrapped in a tight ball for months. But after birth, the sudden absence of your uterine wall allows her to spin her arms . . . whack herself in the face . . .” (emphasis added).31 Karp goes on to state: “A newborn’s brain is so immature that it has a hard time controlling that little body. Sometimes, babies want to suck a finger but end up poking a thumb in their eye instead of their mouth” (emphasis added).32 Karp’s words in these quotes echo historical justifications for swaddling, in particular that infants are born soft and weak, are vulnerable to “evil,” and pose a threat to themselves.

Ralph Frenken, a contemporary German psychologist, is critical of Karp’s views and of swaddling in general. Frenken claims that Karp “romanticizes” the history of swaddling and argues against the validity of Karp’s “calming reflex,” his likening of swaddling to the intrauterine environment, and the assertion that prolonged infantile sleep is normal and inherently beneficial.33 Rather than seeing swaddling as the panacea for new parenting woes, Frenken voices concerns about the developmental and psychological impact of swaddling on infants. According to Frenken, “Swaddling ‘works’ because it forces the baby to sleep.”34 He continues, “An active baby turns into a creature, which is more passive than the fetus ever was.”35 Frenken argues that swaddling robs babies of developmentally important sensory input, impedes their ability to motorically express themselves, and interferes with caregiver-infant bond formation.36

Taking a broader view of contemporary medical evidence, there remains uncertainty around the benefits versus risks of swaddling, stemming from a paucity of studies, especially randomized control trials, as well as variability in swaddling practices, which hinders interpretation of investigative results.37 While some areas of risk are well-established, such as the relationship between tight swaddling around the hips and hip dysplasia, many lack clarity, such as the impact of swaddling on infant development, respiratory tract infections, and maternal-infant interactions.38

One of the most controversial topics within the swaddling debate is Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS).39 While proponents of swaddling such as Karp suggest that swaddling may prevent SIDS,40 there is some evidence that snug wrapping actually increases SIDS risk,41 especially under certain conditions such as prone positioning and loose swaddling material.42 To date, most medical organizations, including the Canadian Pediatric Society and American Academy of Pediatrics, have refrained from providing definitive guidance around swaddling.43

In conclusion, the millennia-old practice of swaddling has seen a resurgence in the West, following its relative abolition in the eighteenth century. While methods of swaddling have changed, justifications echo those of the past, and uncertainty around safety persists. Contemporary caregivers face a lack of clear guidelines when it comes to swaddling, underscoring the need for further research into swaddling’s benefits and risks.

End notes

- Peter N. Stearns, Childhood in World History (New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2017), 1.

- Ralph Frenken, “Psychology and History of Swaddling. Part One: Antiquity Until 15th Century,” The Journal of Psychohistory 39, no. 2 (Fall 2011): 93-94.

- Earle Lipton, Alfred Steinschneider, and Julius B. Richmond, “Swaddling, A Child Care Practice: Historical Cultural, and Experimental Observations.” Pediatrics 35, no. 3 (March 1965): 522.

- Frenken, “Psychology and History of Swaddling. Part One: Antiquity Until 15th Century,” 84.

- Antonia M. Nelson, “Risks and Benefits of Swaddling Health Infants. An Integrative Approach,” The American Journal of Maternal/Child Nursing 42, no. 4 (July/August 2017): 217.

- Frenken, “Psychology and History of Swaddling. Part One: Antiquity Until 15th Century,” 85.

- Ralph Frenken, “Psychology and History of Swaddling. Part Two: The Abolishment of Swaddling From the 16th Century Until Today”, The Journal of Psychohistory 39, no. 3 (Winter 2012): 119-121.

- Ibid., 223-224.

- Ibid., 239-240.

- Stearns, Childhood in World History, 1.

- Frenken, “Psychology and History of Swaddling. Part Two: The Abolishment of Swaddling From the 16th Century Until Today,” 240-241; Lipton, Steinschneider, Richmond, “Swaddling, A Child Care Practice,” 521; Bregje E. van Sleuwen et al., “Swaddling: A Systemic Review,” Pediatrics 120, no. 4 (October 2007): e1098.

- Frenken, “Psychology and History of Swaddling. Part Two: The Abolishment of Swaddling From the 16th Century Until Today,” 227, 230.

- Ibid., 229.

- Ibid., 222-231.

- Ibid., 222.

- Ibid., 222,226.

- Ibid., 222

- Ibid., 225.

- Lipton, Steinschneider, Richmond, “Swaddling, A Child Care Practice,” 527.

- Frenken, “Psychology and History of Swaddling. Part Two: The Abolishment of Swaddling From the 16th Century Until Today,” 227.

- Ibid., 227, 229, 231.

- Ibid., 229

- Ibid., 229

- Ibid., 229-230.

- van Sleuwen, “Swaddling: A Systemic Review,” 1.

- Frenken, “Psychology and History of Swaddling. Part Two: The Abolishment of Swaddling From the 16th Century Until Today,” 233; Emily McDonnell, and Rachel Y. Moon, “Infant Deaths and Injuries Associated with Wearable Blankets, Swaddle Wraps, and Swaddling,” Journal of Pediatrics 164, no. 5 (May 2014): 1153; Nelson, “Risks and Benefits of Swaddling Healthy Infants,” 219-220.

- Nelson, “Risks and Benefits of Swaddling Healthy Infants,” 216-223.

- Harvey Karp, The Happiest Baby Guide to Great Sleep (New York: William Morrow Paperbacks, 2013): 61.

- Ibid., 64-67.

- Ibid., 61.

- Ibid., 66.

- Ibid., 68.

- Frenken, “Psychology and History of Swaddling. Part Two: The Abolishment of Swaddling From the 16th Century Until Today,” 233-235.

- Frenken, “Psychology and History of Swaddling. Part One: Antiquity Until 15th Century,” 90.

- Frenken, “Psychology and History of Swaddling. Part Two: The Abolishment of Swaddling From the 16th Century Until Today,” 238.

- Ibid., 238; Frenken, “Psychology and History of Swaddling. Part One: Antiquity Until 15th Century,” 89.

- Nelson, “Risks and Benefits of Swaddling Healthy Infants,” 222.

- Ibid., 216, 217, 219-22.

- Kristy Kennedy, “Unwrapping the controversy over swaddling,” AAP News 34, no. 6 (June 2013): 1-2.

- Karp, The Happiest Baby Guide, 71.

- Anna Pease et al., “Swaddling and the risk of sudden infant death syndrome: A Meta-analysis,” Pediatrics 137, no. 6 (June 2016): 1-9.

- Nelson, “Risks and Benefits of Swaddling Healthy Infants,” 222.

- Ibid., 220, 222; Carly Weeks “To swaddle or not to swaddle? That’s the new parental question,” The Globe and Mail, September 23, 2012. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/life/parenting/to-swaddle-or-not-to-swaddle-thats-the-new-parental-question/article4560252/

Bibliography

- Frenken, Ralph. “Psychology and History of Swaddling. Part Two: The Abolishment of Swaddling From the 16th Century Until Today.” The Journal of Psychohistory 39, no. 3 (Winter 2012): 119-245.

- Frenken, Ralph. “Psychology and History of Swaddling. Part One: Antiquity Until 15th Century.” The Journal of Psychohistory 39, no. 2 (Fall 2011): 84-114.

- Karp, Harvey. The Happiest Baby Guide to Great Sleep. New York: William Morrow Paperbacks, 2013.

- Kennedy, Kristy. Unwrapping the controversy over swaddling. AAP News 34, no. 6 (June 2013): 1-2, doi:10.1542/aapnews.2013346-34.

- Lipton, Earle L., Alfred Steinschneider, and Julius B. Richmond. “Swaddling, A Child Care Practice: Historical, Cultural, and Experimental Observations,” Pediatrics 35, no. 3 (March 1965): 519-567.

- McDonnell, Emily, and Rachel Y. Moon. “Infant Deaths and Injuries Associated with Wearable Blankets, Swaddle Wraps, and Swaddling,” Journal of Pediatrics 165, no. 5, (May 2014):1152-1156, doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.12.045.

- Nelson, Antonia M. “Risks and Benefits of Swaddling Healthy Infants. An Integrative Review,” The American Journal of Maternal/Child Nursing 42, no. 4 (July/August 2017): 216-225, doi: 10.1097/NMC.0000000000000344.

- Pease, Anna S., Peter J. Fleming, Fern R. Hauck, Rachel Y. Moon, Rosemary S.C. L’Horne, Monique P. L’Hoir, Anne-Louise Ponsonby, and Peter S. Blair, “Swaddling and the Risk of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome: A Meta-Analysis,” Pediatrics 137, no. 6 (June 2016): 1–9, https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-3275.

- Stears, Peter N. Childhood in World History. 3rd ed. New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2017.

- van Sleuwen, Bregje.E., Adele C. Engelberts, Magda M. Boere-Boonekamp, Wietse Kuis, Tom W. J. Schulpen and Monique P. L’Hoir, “Swaddling: A Systemic Review.” Pediatrics 120, no 4. (October 2007): e1097-e1106, doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2083.

- Weeks, Carly. “To swaddle or not to swaddle? That’s the new parental question,” The Globe and Mail, September 23, 2012. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/life/parenting/to-swaddle-or-not-to-swaddle-thats-the-new-parental-question/article4560252/

JENNIFER C. BORST, MPhil, MDCM, FRCPC, is a pediatrician and certified sleep consultant. She completed her undergraduate degree in Biochemistry through Dalhousie University, followed by a MPhil in Comparative Social Policy through Oxford University. Jennifer subsequently studied medicine at McGill University. She completed her general pediatric training through the University of Toronto and subspecialty infectious diseases training through Dalhousie University. Among Jennifer’s areas of interest are the cultural and societal forces that shape health care practices and how to best communicate medical knowledge to the public. Jennifer lives in Halifax, Nova Scotia, with her husband and three young children.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 11, Issue 3 – Summer 2019 & Volume 15, Issue 1 – Winter 2023