Harsh Patolia

Roanoke, Virginia, United States

|

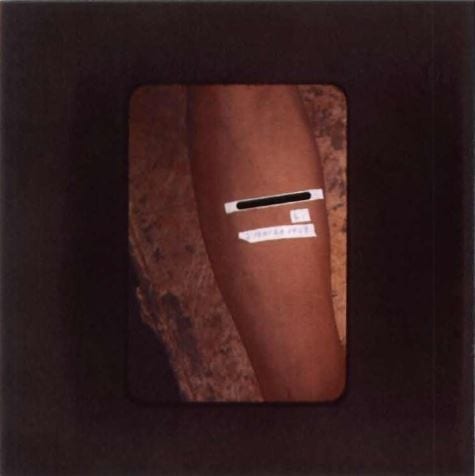

| Inoculation site of participant. Image from the Records of Dr. John C. Cutler housed in the National Archives. |

In 2005, medical historian Dr. Susan Reverby foraged through boxes in the stuffy archives of the library of the University of Pittsburgh for the papers of Thomas Parran, the surgeon general who oversaw the infamous Tuskegee syphilis experiments of the mid-twentieth century. She had embarked on a quest to expose details of the unethical clinical study in which African-American men — predominantly uneducated, impoverished sharecroppers — were withheld treatment for syphilis under the supervision of the United States Public Health Service (USPHS).1 Given placebos instead, unknowing and unwitting patients were told they were being treated for “bad blood.”2 In return, the USPHS rewarded patients with free physical exams, meals, and burial insurance. The American government operated in the shadows for almost forty years, supporting and encouraging the local physicians of Macon County, Alabama to withhold treatment for these unknowing patients as they carefully studied the progression of this debilitating disease.2

Caused by the spirochete Treponema pallidum, the wide spectrum of clinical manifestations of syphilis has earned this disease the monicker “the Great Imitator.” This sexually transmitted disease begins as a painless genital chancre. The secondary phase is characterized by the formation of contagious mucosal and cutaneous rashes. Without treatment, this second stage may resolve on its own; however, the infection can also enter an asymptomatic “latent” stage. Years later, patients in this stage may progress to an even more serious tertiary phase of infection, which includes the formation of mycotic aneurysms and development of neurosyphilis.3

Reverby had dedicated much of her writing to uncovering the truths of the Tuskegee experiments, rectifying a commonly held belief that patients were inoculated in these studies.1 She was a member of the Legacy Committee that ultimately led to a federal apology delivered by President Bill Clinton in 1997.4 Her research had now brought her to the archives of the University of Pittsburgh, where Parran had served as dean of the School of Public Health from 1948 to 1953. There she happened upon the papers of Dr. John Cutler, a Public Health Service official and one of the chief architects and later public defender of the Tuskegee experiments.1

As she perused boxes, Reverby uncovered thousands of pages and photographs under a single cover page entitled “Experimental Studies on Human Inoculation in Syphilis, Gonorrhea, and Chancroid.” Cutler had supervised this study with Juan Funes, the Director of the Venereal Disease Control Division of the Guatemalan Sanidad Publica. From 1946 to 1948, 1308 Guatemalan “men and women who were sex workers, prisoners, mental patients, and soldiers” were deliberately infected, unlike in Tuskegee, with syphilis, gonorrhea, and chancroid.1 Only three years before the study, penicillin had been shown to effectively cure early syphilis infection. Yet the American government had a vested interest in determining whether prophylaxis with penicillin or an arsenic-based agent called “orvus mapharsen” could protect persons from infection after exposure to syphilis, gonorrhea, and chancroid. This study offered an easy answer to that question.1 But why Guatemala?

In 1944, socialist Juan Jose Arevalo was elected to Guatemalan presidency after the deposition of Jorge Ubico, whose presidency had been marred by strict military rule and repression of basic civil rights.5 Previously self-exiled, Arevalo returned after Ubico’s downfall. Arevalo’s six-year term was notable for socialist reconstruction of the agrarian Guatemalan infrastructure and a reorganization of the country into a left-leaning state. Against a backdrop of nationalist and socialist fervor, Arevalo began instituting sweeping changes to the Guatemalan economy, forcing coalitions of American companies out of the country.6 While relations between the Guatemalan and American governments soured, the focus of Guatemalan Public Health Service was not informed by the diplomatic zeitgeist. Like other branches of the Guatemalan bureaucracy, those employed by the Guatemalan Public Health Service were not necessarily champions of the fierce political shifts that had been spearheaded by Arevalo. Many government employees had seen years of revolutionaries like Arevalo rising and falling in power. Flux in political management failed to stagnate the interests of certain government services such as Public Health Service. In a diplomatic relationship that otherwise diverged at every political bullet point, both American and Guatemalan governments agreed that protecting the sexual health of their citizenry was vital.7

In 1946 Cutler, a thirty-two-year-old researcher at the time, had been tasked by Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) director Dr. John Mahoney to investigate a solution to the high incidence of venereal disease among returning American soldiers from the European and Pacific recent world war. Juan Funes, a former collaborator of Cutler’s at the VDRL in Staten Island, offered an experimental population that was vulnerable, uneducated, and not American — Guatemalan sex workers.7 After a grant review by a committee composed of faculty from institutions such as Johns Hopkins, Harvard, and the University of Pennsylvania, and just one year after the Nazi atrocities of the Holocaust had been made public, Cutler and company left for Guatemala City.8

These carefully designed studies involved first inoculating Guatemalan sex workers with Treponema pallidum at medical clinics. Though penicillin’s curative effects in the early stages of syphilis had been discovered a mere three years earlier, researchers intended to study its prophylactic efficacy against orvus-mapharsen, which was a solution that was to be applied in the genital area immediately after sexual intercourse. Male volunteers from la Penitenciaría Central (Central Penitentiary) became test subjects that could be carefully followed by researchers in a contained environment.9 Guatemalan sex workers infected with syphilis were compensated by Cutler with US taxpayer dollars to have sex with Guatemalan prisoners at the penitentiary. As inmates began resisting the repetitive blood draws needed for the study, Cutler expanded the experiments to include an orphanage, a leprosarium, army barracks, and Guatemala’s only mental hospital.1 At the orphanage, 438 children aged six to sixteen were tested for syphilis, and three children found to have signs of congenital syphilis after testing were provided antibiotic treatment.10

With the apparent failures of the prison experiments, researchers turned to the single mental hospital in Guatemala for inoculation test subjects — where “it was not possible to introduce prostitutes, follow the inmates around to watch and time their sexual encounters, or gain the acceptance of the female patients for physical examinations.”10 Inoculums were developed from “scrapings of the chancres on bodies of already infected asylum inmates, or on men from the army who had a ‘street strain,’ picked up by local prostitutes not involved in the study itself.”10 Rabbits were flown in from the VDRL in Staten Island to isolate inoculums. Once the inoculating agents were centrifuged with beef broth, they were usually administered under the foreskins of male patients or directly into the bloodstream of female patients.10 Inoculums were delivered in more than one way, including: “skin contact, direct injection, scarification/abrasion of arms, faces, penises and cervixes, cisternal and lumbar punctures.”1 All that were infected were administered different types of chemical prophylaxis. Though everyone inoculated was to be given penicillin and “supposed to be cured,” preliminary analyses by Dr. John Douglas of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention suggest that 14% of the subjects in the syphilis studies (out of total of 696 exposed subjects) may have not received adequate treatment.10 In the other wings of the study, “99.5%” of the 722 in the gonorrhea group and “93%” of the 142 in the chancroid group were cured. These numbers indicate subjects rather than individuals, as records suggest that many subjects participated in multiple wings of the studies.10 Though Cutler stated that all “participants” in the study received treatment, the documentation of that treatment in the study is incomplete.8

Reverby’s report of these trials revealed that leading officials in the USPHS were aware of the studies in Guatemala and actively “concerned about the knowledge of the study spreading.”1 Unlike Tuskegee, there were few publications of the Guatemala syphilis studies — all of them regarding only the serologic studies in the experiments. A major review of inoculation experiments co-authored by Cutler and published in 1956 failed to mention the Guatemalan syphilis trials.11 Many who participated in the Guatemalan syphilis trials — victims and perpetrators — may be unknown forever. A formal apology was delivered by then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton in 2010, more than sixty years after Cutler and his colleagues began inoculating subjects with syphilis in Guatemala City. There have been no reparations.1 In her report, Reverby reasons that the intentions of the Guatemalan syphilis study should be considered contextually, writing that “why governments and medical professionals might agree to such a study in an under-resourced area, especially when efforts at ‘goodwill’ included the training of personnel, lab supplies, and drugs, never gets much attention.”1 The Guatemala studies quite frankly represent severe lapses in clinical research practices. However, perhaps even more dubiously, they illustrate the leniency with which the American government knowingly operated outside the bounds of previously established research ethics, violating the rights of vulnerable populations. Their ethical infractions must also be examined contextually, for “they thought it was their responsibility to protect the nation through this kind of research.”1 Thus, a systematic understanding of the interests of parties involved in the Guatemalan tragedy could be the most effective form of insurance to prevent history from repeating itself. Changing the institutional environment that permitted these atrocities in the first place is derived not from the theatrics of apologies, reparations, or pathos, but from an understanding of the environment that drove it in the first place. Perhaps, therein lies the key to ensuring that the victims of the Guatemalan experiments do not become a forgotten many.

References

- Reverby SM. Ethical Failures and History Lessons : The U. S. Public Health Service Research Studies in Tuskegee and Guatemala. 34(1):1-18.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. U.S. Public Health Service Syphilis Study at Tuskegee. https://www.cdc.gov/tuskegee/timeline.htm. Published 2015.

- Peeling RW, Hook EW. The pathogenesis of syphilis : the Great Mimicker , revisited. 2006:224-232. doi:10.1002/path.1903.

- Wellesley College. Susan M. Reverby. https://www.wellesley.edu/wgst/faculty/reverby.

- Grieb K. American Involvement in the Rise of Jorge Ubico. Inst Caribb Stud UPR, Rio Pedras Campus. 2019;10(1):5-21. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/25612190.pdf?refreqid=excelsior%3Aab425f1394930cc3584e21e100aa4056.

- Gleijeses P. Juan Jose Arevalo and the Caribbean Legion. 2019;(March 1945):133-145.

- Gallagher-Cohoon E. Dirty Little Secrets: Prostitution and the United States Public Health Service’s Sexually Transmitted Disease Inoculation Study in Guatemala. 2016.

- Zenilman J. The Guatemala Sexually Transmitted Disease Studies : What Happened. 2013;00(00):1-3. doi:10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31828abc1b.

- Presidential Commission for the Study of Bioethical Issues. ETHICALLY IMPOSSIBLE: STD Research in Guatemala from 1946 to 1948. Washington, D.C; 2011.

- Reverby SM. “ Normal Exposure ” and Inoculation Syphilis : A PHS “ Tuskegee ” Doctor in. 2010;23(1):1946-1948. doi:10.1017/S0898030610000291.

- Agnuson H, Evan T, Olansky S, Kaplan B, Mello L De, Cutler J. Inoculation Syphilis in Human Volunteers. Medicine (Baltimore). 1956;35(1):33-82.

HARSH PATOLIA is a third-year medical student at the Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine in Roanoke, Virginia, with a degree in biophysics from Wake Forest University. He enjoys performing music and plays saxophone and piano with a few bands in the Roanoke Valley. He intends to pursue a residency in internal medicine and a fellowship in cardiovascular disease.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 11, Issue 4 – Fall 2019

Spring 2019 | Sections | Infectious Diseases

Leave a Reply