Liz Jones

Aberystwyth, Wales, UK

|

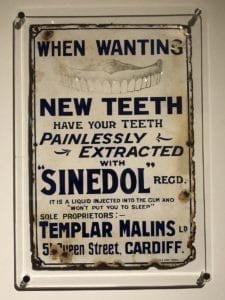

| Enamel plaque advertising the dentist Templar Malins, featuring the Novocaine- based anaesthetic Sinedol. Cardiff, circa 1907. Teeth. 17-May – 16 Sept. 2018, Wellcome Collection, London, UK |

My gran would pull a miniature silver blade from its mother-of-pearl handle and slice the apple into six pieces to share between the two of us. Eating it that way aided digestion, she would tell me. I was not sure what digestion was, or why it needed our aid, but I loved the sense of occasion she brought to this simple act. Today, this sharing of the apple, and the elegant fruit knife she used for it, reminds me of the childhood summers I spent with her. I did not know it then, but it was a ritual she had created out of necessity; that even if she had wanted to, she could not have bitten an apple whole.

On top of her bathroom cabinet sits a curious-looking mug. It has a missing handle, a faded image of the young Queen, and a brown-stained chip on its rim. I climb on a chair to examine it. As I tease it into my hand, a trickle of water slips over the side and splashes on my upward-turned face. It smells of antiseptic. Inside, bobbing in a cloudy liquid, is a full grinning set of teeth with candy pink gums. They look like the teeth I had seen once in the window of a joke shop in Blackpool. But I cannot imagine what my gran would be doing with a set of joke teeth.

|

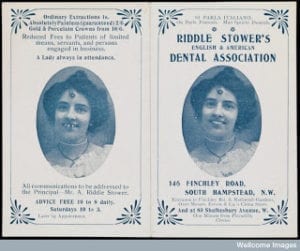

| Advertising card for the London-based Riddle Stower’s English & American Dental Association, 1900. Wellcome Collection, London, UK |

No, they are not a joke, she tells me. They are as good as, better than, real teeth. When she was twenty-one she had her own teeth taken out. No, there was nothing wrong them, it just needed doing. She had gone to London to take up a position as a nanny. The Depression had come early to her south Wales mining town and London was her escape. When her new employers gave her a five pound note for her twenty-first birthday, she knew exactly how she was going to spend it. She took it straight to the dentist to have all her teeth removed and replaced with a set of dentures. She had no doubt that her natural teeth were not worth keeping. She was “well shot” of them, she told me. Dentures (they were always dentures, never false teeth) were her dream; her objects of desire. She was not so naïve as to think they would last forever, as some advertisements claimed, but at least they would not keep her up all night pacing the floor with toothache; would free her from the threat of expensive dental fees to come. Apart from the occasional rubbing of a new set (teething problems, you might say), she insists that all the dentures that followed (eleven in all) have been as blissfully pain-free as her maiden ones. As she says this, I try not to stare at her two rows of small, white, improbably symmetrical teeth.

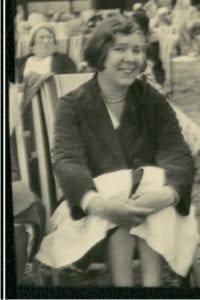

I have a photograph of her as a young woman. She is sitting on a deckchair on Brighton beach. She sits upright, as upright as you can on a deckchair, wearing a half-shy, half-playful smile. Her teeth are large and imperfect and they stick out a little. I like them. They are friendly teeth; full of personality. Two months later, they will be gone.

|

| Enamel plaque advertising the dentist Templar Malins, featuring his ‘Smile of Satisfaction’ offer of free extractions with every new set of £5 dentures purchased. Cardiff, circa 1907. Teeth. 17-May – 16 Sept. 2018, Wellcome Collection, London, UK |

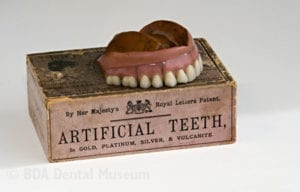

When it came to her dentures, my gran was not one to cut corners. With their porcelain teeth and vulcanite rubber base (the hard-wearing rubber-sulphite compound developed in America by Charles Goodyear), her first set marked the latest in comfort and durability. They were modern dentures for the modern girl; dentures that would allow her to eat, drink, and talk. Above all, they were a million miles away from those monstrosities of the previous century, with their clumsy ivory or gold bases and—worst of all—those springs that could send them leaping out of the wearer’s mouth.1

After the vulcanite patent expired in 1881, the cost of dentures plummeted. Now even maids and shop girls could aspire to a set.2 Quick to respond to the growing demand, dentists began offering special rates for servants “and others of limited means.”3 This new market was not confined to the capital. In my gran’s native Wales, the dentist Templar Malins ran an eye-catching “Smile of Satisfaction” campaign, which offered free extractions with every five guinea set of “replacement teeth.” (“They never change colour, never wear out.”) During the early 1900s, Malins’s distinctive blue, green, and red enamel advertising plaques—with their two fashionably dressed women and an equally fashionably dressed man, all bearing flawless white smiles —became familiar sites on the streets of Cardiff.4

In the popular press, advertisements for “artificial teeth” jostled against those for corsets, hair renewal creams, and other staples of the classified pages. With their standard motif of the before and after shot of a young woman—her dazzling white smile juxtaposed with a shameful gap-toothed version—they rebranded dentures as something more than substitutes for natural teeth. With slogans like “Are you afraid to laugh?” natural teeth became sources of embarrassment, with dentures their more hygienic, durable, and above all, cosmetically superior alternative.5 The advertisements may have been crude, but they persuaded thousands of usually young, usually women, to trade in healthy teeth for the promise of a perfect smile.

|

| Set of vulcanite dentures with porcelain teeth. The black vulcanite rubber is covered with sections of pink porcelain, creating a more natural appearance around the gums. As the first wearable and functional set of dentures, vulcanite dentures were a major innovation. British Dental Association Museum Collection, London, UK |

The arrival of Novocaine further fuelled demand. Thanks to this new “wonder” anesthetic, teeth could be painlessly extracted to make way for more desirable replacements. With Novocaine as part of their armory, dentists began to offer same-day combined packages of “painless” extractions and denture-fitting.6 Beneath the breezy promises, the reality was often more grisly. While Novocaine was relatively safe and convenient, it also came with a tendency to disappear rapidly from the bloodstream, making it unsuitable for longer procedures. As its anesthetic properties wore off mid-surgery, there would be little choice but to top it up with further injections into already sore and bleeding gums; an experience that would be hard to imagine as anything less than an ordeal.7

Had it been an ordeal for my gran? If so, she never mentioned it. Perhaps she had known it would hurt, had considered it a pain worth enduring. Perhaps she had chosen to forget.

By the time she submitted her teeth to the dentist’s forceps, the advertisements were more discreet than those of twenty years earlier. No longer a novelty, dentures were now the norm. As Hollywood’s perfect smiles beamed out from the silent screens, a new set of teeth became the latest “It Girl” accessory. And if at midnight, Cinderella-like, they had to hide in a dark corner, what did it matter if during waking hours their owner could smile as brightly as Clara Bow?

|

| The author’s grandmother, aged 20, on Brighton Beach, England during the summer of 1927. A couple of months later, she elected to have all her teeth extracted and replaced with a set of dentures. |

This trend had its detractors; among them the poet T.S. Eliot. In a passage from his 1922 epic poem The Waste Land, his contempt for dentures, or rather the practice of treating dentures as accessories, is palpable. In a rare example of literary dental satire, a bar room conversation between two working class women takes a darker turn as one browbeats the other to “get yourself some teeth” for when her husband is demobbed. As the speaker heightens her efforts to coerce her friend, the social pressures to give up natural teeth for a manufactured ideal of beauty, are laid bare:

You have them all out, Lil, and get a nice set,

He said, I swear, I can’t bear to look at you.8

If for Eliot dentures are a signifier of the decline and artificiality of modern life, the playwright Alan Bennet takes a more pragmatic approach. In his memoir Telling Tales, he recalls how as an anxious teenager during the 1940s, he would take it upon himself to wash his parents’ dentures; a “nightly ritual cleansing” motivated by a fear that the “greyish lichen-like fur” that grew on their palates harbored a fatal disease that might leave him orphaned.9

I had no such worries about my gran’s dentures. Unlike Bennet’s parents, she took exemplary pride in them; diligently soaking them each night in an antibacterial wash. The vulcanite set long gone, its successors were made of stronger, more hygienic plastic acrylic. Looking back over her years as a denture wearer, she would insist that she never regretted her decision. If only more people had them, she would say, they would save themselves no end of suffering. If in her later years she no longer boasted about her dentures, she was not ashamed of them either. They would always be part of her youth; part of that bright modern girl with a bright new smile.

Today, as I look back on my own dental history with its fillings, crowns, and bridges, I think of her. As I face another failed bridge and am considering implants, as my dentist advises, I remember my gran’s words. You’d be better off without them, she is saying. Once I would have laughed. Now I am not so certain.

References

- Richard Barnett, The Smile Stealers, London: Thames and Hudson, 2017, p. 165

- Ibid., p. 165

- Ibid., p. 166

- Enamel Plaque advertising the dentist Templar Malins, circa 1907. Teeth. 17 May – 16 Sept. 2018, Wellcome Collection, London

- Booklet advertising Goodall’s Dental Institute, Wellcome Collection, London

- Advertisement for Mr. Smedley’s Dental Surgery, Wellcome Collection, London

- James Wybrandt, The Excruciating History of Dentistry: Toothsome Tales and Oral Oddities from Babylon to Braces, 1998, New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, p. 115

- T.S. Eliot, The Waste Land and Other Poems, 2014, Orlando: Harcourt, Inc. p. 35

- Alan Bennet, Telling Tales, 2000, London: BBC Books, pp. 62-63

LIZ JONES is a writer and creative writing tutor who is drawn to tales of the overlooked and forgotten. Her biography of the now-forgotten bestselling novelist, scriptwriter, actor, and theatre impresario, Marguerite Jervis, will be published in the UK by Honno Press in March 2020.

Spring 2019 | Sections | History Essays

Leave a Reply