Lisa Mulleneaux

New York, New York, United States

Doctors today are relearning lessons from a century ago when overprescription of opioids created an epidemic of addicts, most of whom were upper-class or middle-class women. Eugene O’Neill’s mother, Mary “Ella” Quinlan O’Neill, was one of them, and the playwright’s harrowing portrait of her as Mary Tyrone in Long Day’s Journey into Night presents a woman lost to her husband and two sons in a fog of morphine. The play begins on a sunny morning in August 1912 with affectionate banter at the breakfast table among the parents and their two grown sons. Mary is fully present, but as the euphoric effect of her injections takes hold, she retreats to the shy, convent-educated girl she once was, speaking only to herself, moving “like a sleeperwalker.”1

O’Neill was so concerned that the family drama he called a “play of old sorrow, written in tears and blood” not offend any living relatives that in his will he forbade its production and publication until twenty-five years after his death. His third wife, Carlotta, had other ideas and its world premiere took place in 1956, only three years after O’Neill died. It is not hard to understand the playwright’s squeamishness: in addition to the tortured mother he describes as a “lying dope fiend,” he presents his father, the stage actor James O’Neill, as too miserly to pay for cures. His brother, Jamie, is a cynical, lowlife drunk. In fact, I suggest that Journey is best appreciated, not as a son’s rage and mourning, but as a portrait of four addicts — none of whom can help each other.

Though in his dedication O’Neill claims he wrote Journey “with deep pity and understanding and forgiveness for all the four haunted Tyrones,”2 there is little forgiveness in what his biographer Louis Sheaffer describes as “an inextricable tangle of love and hostility, of compassion and bitter resentment, of accusation and apology, of self-pity and self-hatred.”3 What drives the play, creating the tension that stirs these conflicted feelings, is Mary’s losing battle with the drug she was given to ease her pain after her third son’s birth. Journey opens when that son (O’Neill gives himself the name Edmund) is now twenty-three, and Mary has been trying and failing to quit morphine for as many years. The action concerns her latest relapse.

As an alcoholic until 1925, O’Neill well understood the addict’s self-deception, the ruses invented to avoid disapproval. Whiskey flows freely in the Tyrone household, but Mary’s morphine prescriptions — though legal — are the family’s shameful secret. During Act II (mid-day) the men suspect Mother has “slipped” again as her behavior becomes increasingly nervous and disconnected.

MARY

Sharply.

Please stop staring! One would think you were accusing me—

Then pleadingly.

James! You don’t understand!

TYRONE

With dull anger.

I understand that I’ve been a God-damned fool to believe in you!

He walks away from her to pour himself a drink.

MARY

Her face again sets in stubborn defiance.

I don’t know what you mean by “believing in me.” All I’ve felt was distrust and spying and suspicion.

….

James! I tried so hard! I tried so hard! Please believe—!4

As she sinks into the arms of Morpheus5 during the course of the afternoon, the men discuss a pattern they know intimately.

JAMIE

Shrugs his shoulders.

You can’t talk to her now. She’ll listen but she won’t listen. She’ll be here but she won’t be here. You know the way she gets.

TYRONE

Yes, that’s the way the poison acts on her always. Every day from now on, there’ll be the same drifting away from us until by the end of each night—6

Thinking it might improve her health, her husband encourages Mary to go for a drive. She does so: to fill a new morphine prescription.

TYRONE

Bitterly scornful.

Leave it to you to have some of the stuff hidden, and prescriptions for more! I hope you’ll lay in good stock ahead so we’ll never have another night like the one when you screamed for it, and ran out of the house in your nightdress half crazy, to try to throw yourself off the dock!7

The addict’s need for seclusion versus the desire to free themselves is caught in the final lines of Act II. Mary, standing alone after the men have left says, “It’s so lonely here.”

MARY

Then her face hardens into bitter self-contempt.

You’re lying to yourself again. You wanted to get rid of them. Their contempt and disgust aren’t pleasant company. You’re glad they’re gone.8

Ella O’Neill had a very difficult childbirth in 1888, partly because Eugene weighed eleven pounds. She was given morphine for post-partum pain, a standard treatment, and continued to take her “medicine,” unaware of the hold it was gaining on her. Nor, according to Sheaffer, did her family realize she was addicted, though by 1912 Ella was wandering onstage during James’ performances.9 She sought numerous cures in medical sanitoria but always relapsed, returning to dependence on “that damned poison.”

In 1888, when Ella took her first dose after Eugene’s birth, the majority of morphine and opium addicts in America were women. Stephen Kandall in Substance and Shadow: Women and Addiction in the United States estimates that over 100,000 women at this time were chronic opiate users, many of the upper classes, their physicians sworn to secrecy.10 Getting a prescription for laudanum (a solution of opium dissolved in alcohol or water), paregoric (camphorated tincture of opium), or morphine (an opium derivative) was easy, as these painkillers were used to treat everything from chilblains to mumps. A syringe kit for injecting morphine, as Ella did, was as handy as the Sears and Roebuck catalog, which sold them in 1897 for $1.50.

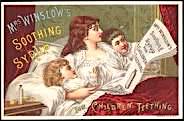

In many cases, physicians relied on opiates because it was all they had to ease their patients’ suffering. By the late nineteenth century, though, they were under attack for overprescribing opiates and druggists for dispensing them without prescriptions.11 But why would you need a prescription? Opium and morphine were readily available in patent medicines and home remedy liniments with names like Mrs. Winslow’s Soothing Syrup and Seeley’s Pile Ointment. This enormously lucrative industry remained unregulated until passage of the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, which required any “dangerous” or “addictive” drugs to appear on the label of products.12

“The weaker sex” were enthusiastically prescribed opiates for reproductive and nervous complaints. No less an authority than the president of the American Gynecological Society declared in 1879 that “for the relief of pain, the treatment is all summed up in one word, and that is opium. This divine drug overshadows all other anodynes… you can easily educate her to become an opium-eater, and nothing short of this should be aimed at by the medical attendant.”13 Most alarming, is that these doctors recommended addictive medicines to their pregnant clients. Dr. Pierce’s Favorite Prescription, which contained opium, was advertised as a tonic for mother and her baby both before and after delivery.

When Mary Tyrone complains of “nerves,” she is referring to a vague disorder, neurasthenia, that was regularly treated with alcohol- and opium-laced medicines. Courtwright cites the case of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s daughter, Georgiana May, who, treated with morphine for depression, became addicted. “The cure had become its own illness,” recounts Stowe. “Georgie burned with a flame that was lighted only by the drug. In its absence, she plummeted into a state from which she could only be rescued by more morphine.”14 Sanitaria, like the one set up by John Harvey Kellogg at Battle Creek, Michigan, offered patients, most of whom were women, exotic cures for their nerves, from breathing exercises to womb manipulation. Ella O’Neill was one for whom their exotic cures were another false promise.

Fortunately, for Eugene O’Neill’s mother there was a cure — just not at Battle Creek. She returned to the Catholic faith she had trusted growing up in Cleveland and sometime in the spring of 1914, Sheaffer speculates, detoxed at a Brooklyn convent. For the last eight years of her life, Ella was drug-free, and the family’s twenty-five-year nightmare was over. Though her son chose not to include this happy ending in Journey, he did forecast it when he has Mary say that some day the Virgin Mary will forgive her and help restore her health. “I will hear myself scream with agony, and at the same time I will laugh because I will be so sure of myself.”15

Ella’s recovery inspired playwright Ann Harson to write Miles to Babylon (2006) with the aim of vindicating Ella O’Neill. “Ella [as painted in “Long Day’s Journey”] was the ruination of her family,” Harson told an interviewer. “She deserved a little more than that.”16 In her play, Ella comes to the convent to throw herself on the mercy of her girlhood mentor, Mother Elizabeth, only to find that Mother Elizabeth is dead. With the help of the new director, Mother Dolores, Ella renews both her health and her Catholic faith.

There was an actual Mother Elizabeth, who gave schoolgirl Ella Quinlan the encouragement her mother did not, arguing for a career as a concert pianist instead of marriage to James O’Neill. At her most desperate, O’Neill’s addicted mother in Journey turns away from her husband’s and sons’ condemnation to recall the most loving face she ever knew.

MARY

…she always understands, even before you say a word. Her kind blue eyes look right into your heart. You can’t keep any secrets from her. You couldn’t deceive her, even if you were mean enough to want to.”17

References

- Eugene O’Neill, Long Day’s Journey into Night, (New Haven, Yale Un. Press, 2014), 177.

- O’Neill, Journey, np.

- Louis Sheaffer, O’Neil: Son and Playwright, (Boston, Little Brown, 1968), 4.

- O’Neill, Journey, 71-72.

- Morphine was named by its discoverer, Friedrich Sertürner, after Morpheus, the Greek god of dreams.

- O’Neill, Journey, 80.

- O’Neill, Journey, 89.

- O’Neill, Journey, 98.

- Sheaffer, O’Neill: Son and Playwright, 22 and 220.

- Stephen R. Kandall, Substance and Shadow, (Cambridge, MA, Harvard Un., 1996), 14-15.

- Kandall, Substance and Shadow, 22. Kandall notes that standard medical textbooks—Pepper (1886), Osler (1894), and French (1903)—all mention the doctor’s role in opiate addiction.

- Barbara Hodgson in In the Arms of Morpheus (2001) lists [at the bottom of each page] over 300 medicines containing opium.

- T. Gaillard Thomas, “Clinical lecture on diseases of women.” Medical Record 16, (1879): 316. Quoted in Kandall, 24.

- David T. Courtwright, “The Female Opiate Addict in 19th-Century America,” Essays in Arts and Sciences 10, (1982):164.

- O’Neill, Journey, 96.

- Jerry Tallmer, “Ella O’Neill’s Long Journey into the Light,” The Villager, (76/22) Oct., 2006, np.

- O’Neill, Journey, 178.

Bibliography

- Black, Stephen A. “Mrs. O’Neill’s Illness,” New York Theatre Wire, nd, http://www.nytheatre-wire.com/sb06093t.htm.

- Courtwright, David T. “The Female Opiate Addict in 19th-Century America,” Essays in Arts and Sciences 10, (1982):161-171.

- ……………………. Dark Paradise: A History of Opiate Addiction in the United States, Cambridge, Harvard Un. Press, 2001.

- Harson, Ann. Miles to Babylon: A Play in Two Acts, Jefferson, NC, McFarland & Co., 2010.

- Hodgson, Barbara. In the Arms of Morpheus, Vancouver, Greystone Books, 2001.

- Kandall, Stephen R., Substance and Shadow: Women and Addiction in the United States, Cambridge, MA, Harvard Un. Press, 1996.

- O’Neill, Eugene. Long Day’s Journey into Night, Ed. Wm. Davies King., New Haven: Yale Un. Press, 2014.

- Sheaffer, Louis. O’Neill: Son and Playwright, Boston, Little Brown, 1968.

- Tallmer, Jerry. “Ella O’Neill’s Long Journey into the Light,” The Villager, (76/22) Oct., 2006. https://www.thevillager.com/2006/10/ella-oneills-long-journey-into-the-light/

LISA MULLENNEAUX’S poems and essays have appeared in Ploughshares, The New England Review, and The Tampa Review, among others. She is the North American translator of the Milanese poet Anna Maria Carpi and the author of Naples’ Little Women: The Fiction of Elena Ferrante. She lives in Manhattan and teaches writing for the University of Maryland UC.

Leave a Reply