Jane Persons

Iowa City, Iowa, United States

|

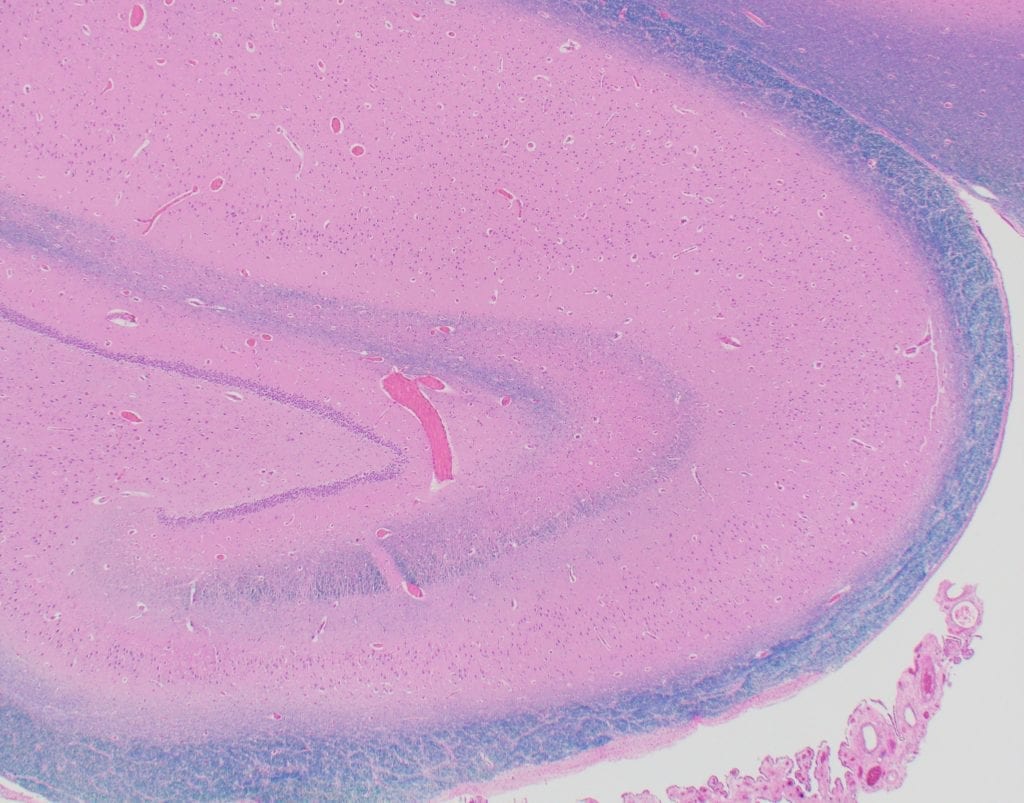

| Human hippocampus, 2X magnification, Luxol fast blue stain. Photo credit: Karra Jones, University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, Department of Pathology, Iowa City, Iowa, United States |

The development of compassion, along with wisdom, skill, and communication, is pivotally important to the practice of medicine.1 Perhaps even more importantly, development of personal character – such as through a medical education that emphasizes ethics, professionalism, and the humanities – is critical to the emergence of effective and caring physicians.2 Integration of individual character into physician identity allows enthusiasm and compassion to take root and flourish.3 Compassion cannot be readily taught, but rather must develop by way of the personal growth attained through metacognition – the self-reflective process of “thinking about thinking” that allows inner awareness to emerge.1,4

This practice of metacognition improves emotional well-being and positive mental health,4 which in turn buffers against the consequences of burnout.5 An estimated half – and perhaps as many as 82% – of all medical students experience burnout during the course of their medical education, with greater susceptibility seen among first year medical students.6-8 Medical students succumb to burnout in a futile attempt to adapt to an environment in which they feel they must turn to detachment and neglect of self-care in order to thrive, which in turn damages personal and professional development, as well as integration of the two.9 Burnout arises as a product of distress, specifically emotional exhaustion, academic inefficacy, and sleep difficulty, and its effects are compounded by depression and cynicism.10,11 The more distress experienced by a medical student, the greater the impact on physical and psychological health10,11 and the more likely they will be to drop out of medical school or, more seriously, to become suicidal.12

Metacognition

Metacognition, as outlined by Quentin Eichbaum, allows for development of the ability to navigate uncertainty, reason through complex scenarios, and recognize the variability and diversity of the human condition, which in turn improves one’s ability to predict the thoughts and feelings of others – or, in other words, to empathize.4 Metacognition is an umbrella term that incorporates both the practice of mindfulness meditation and the practice of introspection. Meditation, the state of objectless loving-kindness and compassion,13 often involves the practice of mindfulness – awareness and acceptance of the present moment and disengagement from attachment. Mindfulness fosters compassion through the practice of nonjudgmental recognition of and disengagement from one’s own beliefs, thoughts, and emotions. Mindfulness is important because it improves the ability to cope14 and to empathize,15 and has also been shown to improve mood,16,17 increase immune response,17 and reduce stress.18-20 Similar to mindfulness, introspection is also concerned with nonjudgmental recognition of one’s own beliefs, thoughts, and emotions; however, in contrast to the intent of disengaging with one’s own beliefs, thoughts, and emotions to foster deeper acceptance and connectedness, introspection involves directly engaging with one’s own beliefs, thoughts, and emotions to develop an accurate self-perception. In short, introspection is the act of engaging with and describing one’s conscious internal experience.21,22 This act of engaging with one’s inner self improves the ability to manage emotions. This is supported by neuroimaging research conducted by Herwig et al., who noted that emotion-introspection depressed amygdala activity, thus reducing emotion arousal and allowing for emotional regulation.23

There is strong evidence to suggest that the internally reflective tasks of metacognition are executed through the brain’s default mode network, a diffuse area of the brain that becomes active when an individual is not engaged in an external task. The anatomical components of the default mode network are the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, the posterior cingulate/retrosplenial cortex, inferior parietal lobule, lateral temporal cortex, dorsal medial prefrontal cortex, and the hippocampal formation, which includes the hippocampus, the entorhinal cortex, and the parahippocampal cortex. These regions of the brain are involved in random episodic memory, which plays a role in passively reflecting on the past and planning for the future, as well as in the realms of fantasy, daydream, and the imagining of alternate realities.21,24,25

Metacognition in the Context of Liminal Space

Resnicow et al. suggest that an approach based in Chaos Theory, which is grounded in the idea that small, even seemingly minute changes can have far-reaching repercussions, can be used to pave the way for significant behavior change in the long-term. This is relevant to the discussion of introspective practice in that the small act of creating metacognitive space can lead to the far-reaching outcomes of innovation, creation, clarity, improved emotional stability, mental health, creativity, and inspiration.26

Kabat-Zinn refers to our current state as one of “continuous partial attention,” in which we have access to near-constant mindless distraction in the form of television, text messaging, social media, and so on.14 Through the small act of intentionally maintaining liminal space – rather than filling it with distractions – we can thus create this minute change in behavior from which great changes have the chance to emerge. Liou likens liminal space to the “gutter” – the empty space in between frames of a comic in which we must use our imagination to weave the link between the previous frame and the next. This is also true of the “gutters” of our lived experience, and as such we must similarly use this liminal space, these gutters, these quiet interludes, to weave a web between the past and the future, between the empirical and the theoretical.27

Navigation of the liminal space cannot, however, be accomplished solely in the realm of conscious thought. Rather, one must not only weave between past and future, real and fantastic, but must also travel between the realms of the conscious and the unconscious mind. Mind wandering – the realm of the unconscious mind – is, like metacognition, focused largely on memory, simulated interaction, and hypothetical realities, however an individual engaged in mind wandering is characteristically lacking in self-awareness, and in this sense the mind is closer to the dream state of REM sleep than it is to the metacognitive states of meditation or introspection.28 Flowing between the wandering mind and metacognitive thought during the creative process may be likened to walking along a beach picking up stones, putting most of them back down immediately but stopping to engage in conscious appraisal of others. This integration of engagement and disengagement, through the vehicle of silent contemplation, provides space for themes to emerge spontaneously and allows important connections to be made, in turn creating space for personal and professional growth.

References

- Kern DE, Wright SM, Carrese JA, et al. Personal growth in medical faculty: a qualitative study. West J Med. 2001;175(2):92-98.

- Carey GB, Curlin FA, Yoon JD. Medical student opinions on character development in medical education: a national survey. BMC Res Notes. 2015;8:455.

- Finlay SE, Fawzy M. Becoming a doctor. Med Humanit. 2001;27(2):90-92.

- Eichbaum QG. Thinking about thinking and emotion: the metacognitive approach to the medical humanities that integrates the humanities with the basic and clinical sciences. Perm J. 2014;18(4):64-75.

- Dyrbye LN, Harper W, Moutier C, et al. A multi-institutional study exploring the impact of positive mental health on medical students’ professionalism in an era of high burnout. Acad Med. 2012;87(8):1024-1031.

- Ishak W, Nikravesh R, Lederer S, Perry R, Ogunyemi D, Bernstein C. Burnout in medical students: a systematic review. Clin Teach. 2013;10(4):242-245.

- Mavor KI, McNeill KG, Anderson K, Kerr A, O’Reilly E, Platow MJ. Beyond prevalence to process: the role of self and identity in medical student well-being. Med Educ. 2014;48(4):351-360.

- Fares J, Saadeddin Z, Al Tabosh H, et al. Extracurricular activities associated with stress and burnout in preclinical medical students. J Epidemiol Glob Health. 2015.

- Jennings ML. Medical student burnout: interdisciplinary exploration and analysis. J Med Humanit. 2009;30(4):253-269.

- Pagnin D, de Queiroz V. Influence of burnout and sleep difficulties on the quality of life among medical students. Springerplus. 2015;4:676.

- Pagnin D, de Queiroz V, Carvalho YT, Dutra AS, Amaral MB, Queiroz TT. The relation between burnout and sleep disorders in medical students. Acad Psychiatry. 2014;38(4):438-444.

- Dyrbye LN, Harper W, Durning SJ, et al. Patterns of distress in US medical students. Med Teach. 2011;33(10):834-839.

- Lutz A, Greischar LL, Rawlings NB, Ricard M, Davidson RJ. Long-term meditators self-induce high-amplitude gamma synchrony during mental practice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(46):16369-16373.

- Ludwig DS, Kabat-Zinn J. Mindfulness in medicine. JAMA. 2008;300(11):1350-1352.

- 15. Shapiro SL, Schwartz GE, Bonner G. Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on medical and premedical students. J Behav Med. 1998;21(6):581-599.

- Creswell JD, Way BM, Eisenberger NI, Lieberman MD. Neural correlates of dispositional mindfulness during affect labeling. Psychosom Med. 2007;69(6):560-565.

- Davidson RJ, Kabat-Zinn J, Schumacher J, et al. Alterations in brain and immune function produced by mindfulness meditation. Psychosom Med. 2003;65(4):564-570.

- Tang YY, Ma Y, Wang J, et al. Short-term meditation training improves attention and self-regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(43):17152-17156.

- Erogul M, Singer G, McIntyre T, Stefanov DG. Abridged mindfulness intervention to support wellness in first-year medical students. Teach Learn Med. 2014;26(4):350-356.

- de Vibe M, Solhaug I, Tyssen R, et al. Mindfulness training for stress management: a randomised controlled study of medical and psychology students. BMC Med Educ. 2013;13:107.

- Buckner RL, Andrews-Hanna JR, Schacter DL. The brain’s default network: anatomy, function, and relevance to disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1124:1-38.

- McClelland T. Affording introspection: an alternative model of inner awareness. Philos Stud. 2015;172(9):2469-2492.

- Herwig U, Kaffenberger T, Jancke L, Bruhl AB. Self-related awareness and emotion regulation. Neuroimage. 2010;50(2):734-741.

- Andreasen NC, O’Leary DS, Cizadlo T, et al. Remembering the past: two facets of episodic memory explored with positron emission tomography. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152(11):1576-1585.

- Oosterwijk S, Mackey S, Wilson-Mendenhall C, Winkielman P, Paulus MP. Concepts in context: Processing mental state concepts with internal or external focus involves different neural systems. Soc Neurosci. 2015;10(3):294-307.

- Resnicow K, Vaughan R. A chaotic view of behavior change: a quantum leap for health promotion. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2006;3:25.

- Liou KT, Jamorabo DS, Dollase RH, Dumenco L, Schiffman FJ, Baruch JM. Playing in the “Gutter”: Cultivating Creativity in Medical Education and Practice. Acad Med. 2016;91(3):322-327.

- Fox KC, Nijeboer S, Solomonova E, Domhoff GW, Christoff K. Dreaming as mind wandering: evidence from functional neuroimaging and first-person content reports. Front Hum Neurosci. 2013;7:412.

JANE PERSONS is a medical student at the University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine. Prior to entering medical training, she completed a doctoral program in Epidemiology with a focus on mental health epidemiology. Dr. Persons’ interest in the integration of humanities into medical practice stems from the firm belief that honoring and promoting the mind-body connection is critical to health, wellness, identity, and belonging.

Winter 2019 | Sections | Psychiatry & Psychology

Leave a Reply