Gaetan Sgro

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, United States

|

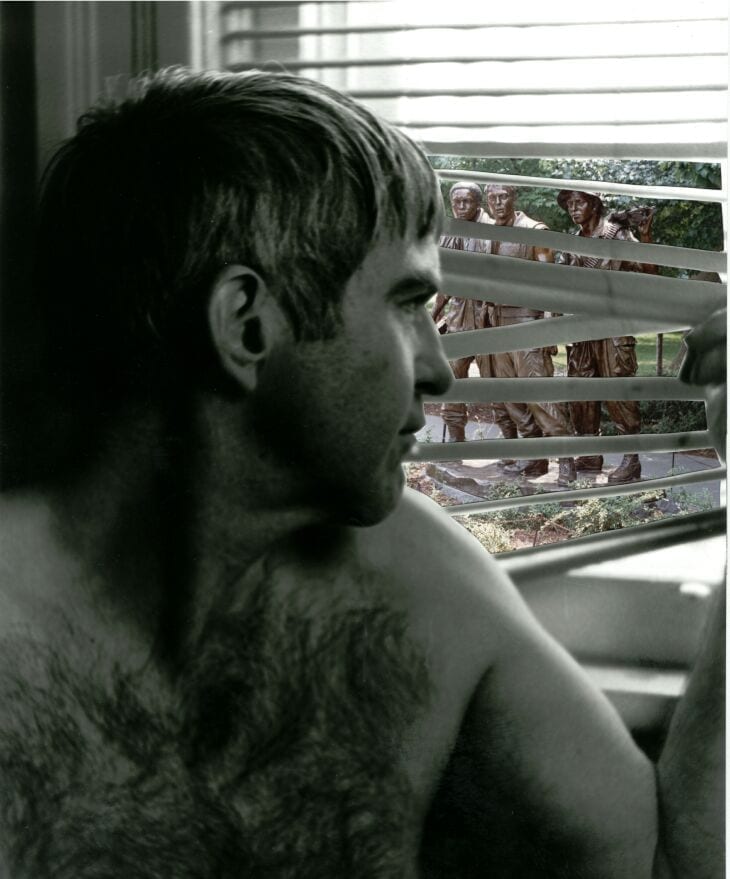

| Looking Back: Vietnam War Memorial by Ann Stuurman. 2002. Windfield Photographic Collection, Ontario Canada. |

noun

1. an expression of will or intent; a commitment

In June 1965, Edward White, one of two astronauts aboard the Gemini IV mission, becomes the first American to walk in space. He floats free of the capsule for twenty minutes, and is so transfixed by the experience that Gus Grissom, a member of the support crew in Houston, has to shout at him over the radio to “get back in!” It will be another twenty-five years before Voyager I and Carl Sagan place our “Pale Blue Dot” in context, but White is already beginning to get it. Through bursts of static, he can be heard describing his reentry as “the saddest moment of my life.”

That same month, General Westmoreland advises the Joint Chiefs that he sees “no course of action” other than to increase the American troop presence in Vietnam. Anti-war protestors stage a teach-in at the Pentagon. A skinny, Italian kid from South Philly becomes the first member of his family to graduate from college.

That kid, who will become my father, is South Philly through and through, the son of a dressmaker and a carpenter who are one generation removed from the shin of Italy’s boot. He has never left home and has no firm career plans. Now is not a good time to be a free agent.

“I can’t say I feared service in Vietnam as much as I loathed the idea of spending two years in the Army in any capacity,” he told me recently. My father is proud, scrappy, skeptical of institutions. He has never been good at taking commands.

Five decades later, in a hospital across the state, a Vietnam Veteran named Ken Atkins (not his real name) is admitted to my service. Ken is younger than my father but does not look it. He looks tired of fighting. He understands, now, that submission is the final show of strength. Today, he takes his medicine, and lets a nurse scrape the stubble from his face.

Ken Atkins enlisted in the Army. He believes there is no one else to blame. Today, propped on his blue, plastic mattress, he reflects on the turn in his story. “I didn’t even have to go — I volunteered. They sent me to Germany first, but I volunteered to go because I thought, why else am I doing this if I’m not going to go where I’m needed?” Pale light breaks in through the shade. The silence that follows omits a litany of consequences; also, a separate, unwritten history.

Today, Ken’s liver is failing, literally. Today, we are so accustomed to irony that we forget what literally means. A man like Ken Atkins can say — literally — that he offered his life for his country. His country cannot say, exactly, what it did with Ken’s life.

noun

2. the process or capability of making distinguishable closely adjacent objects or images

In June 1965, only a long, golden tether separates Ed White from the infinite. He sees his life from the outside-in, and feels his consciousness expand. The other crew members have to snap him out of it, pull him back in, and secure the hatch.

Miles below, the President orders an expansion of the draft from 17,000 to 35,000 young Americans per month. My father figures he’s next. In August, he buses thirty-six blocks to an Army reserve unit at 17th and Wood and adds his name to their list. The Reserves plan to swear him in in September and advise him to inquire with the local draft board about his position. He is relieved to hear that he will not be on the September call. Probably October at the earliest. He waits for the dog days to get on with their business. One week later, he gets a letter stating he has been drafted.

There comes a point, when caring for a person near the end of his life, at which you feel less like doctor and more like a minister. I listen to Ken Atkins’ confession, and understand that for him, the war is not past. He attributes his illness to the “sins of youth,” by which he means the consequences of believing that one’s youth is infinite. He means nerves frayed by the randomness of “toe poppers,” by the low, resonant rat-a-tat-tat of air cover strafing a village. He means chemical defoliants, political ideologies, and other weapons of mass destruction.

In August of ’65, my father pauses on the front stoop of his parents’ row house. On the corner, bare-chested boys pry the cap off a hydrant while he stares down at the letter.

The next morning, he marches north on Broad Street to a Navy recruiting office, and tries to enlist, only he has forgotten his college transcript. Come back tomorrow and we’ll swear you in. Over the telephone, he informs the Army Reserve unit that they can scratch his name from their list. There is a pregnant pause on the other end; a separate, unwritten history stretches before him. “Where are you right now?” the man finally asks. “Home,” my father says. “Can you get up here this afternoon to take the oath?” I was in his office before he could hang up the phone, is how my father always tells it.

I do not know the first thing about Ken Atkins’s sins, but I assume that he has paid for them. Before he is discharged, we share one final moment. It is the conversation in which he tells me about his volunteering to go “in country.” I try to commend his courage, but my words sound flat and Ken does not seem interested. His eyes are fixed, and not like he is looking ahead.

“You step off the airplane in Washington and the cabs just fly right by. People want to throw drinks at you in the street. I’m not sure they ever officially declared that a war — Vietnam. Not that I’m aware of.”

In 1980, when the Voyager I space probe drifted past Saturn, effectively completing its mission, the astrophysicist Carl Sagan proposed that the spacecraft take one last photograph of Earth from the edge of our solar system. Skeptics feared that directing the camera’s gaze backward, into the sun’s harsh rays, would damage it. Complex calculations were required to capture an image with sufficient resolution from such distance. Eventually, an image depicting a speck of light against a vast darkness returned to its subject. The vision of Earth from three billion miles away had taken ten years to make, and it has haunted us ever since.

When Ken Atkins came home from the fighting, people took to the streets in protest. On April 30, 1975, North Vietnamese tanks overtook Saigon’s Presidential Palace. On July 17, 1976, my parents took vows in a chapel at graduate school. For one week in early summer nearly forty years later, I took care of Ken Atkins, who died shortly after leaving the hospital. When a doctor first engages a patient, he calls it “taking a history.” I took Ken Atkin’s history, and I will never be able to give it back.

noun

3. The point in a literary work at which the chief dramatic complication is addressed

Two years after his history-making spacewalk, Ed White was seated in a cramped capsule between fellow astronauts Virgil “Gus” Grisson and Roger Chaffee, during prelaunch testing for the first Apollo mission. One of Ed’s jobs was to open the hatch in case of an emergency, but when a fire broke out in the sealed cabin, he never had a chance. When they recovered Ed’s body, his arms were still outstretched.

How subtle the breaks that separate one fate from the next. It is comforting to imagine that in some alternate universe, perhaps Ed and the others make it. Perhaps they live to fly a lunar mission. Perhaps?

My kids have been fortunate to know their grandfather, a former teacher, counsellor, and ultimately, the director of a non-profit that serves the homeless. What if he had not picked up the phone to notify the Reserves that day?

Whenever I am on service over a holiday, I like to take my oldest daughter to work with me. I ask her to stand at attention, to smile and wave as I examine my patients. I want her to understand what our veterans have given. I want her to appreciate sacrifice, gratitude, and the vagaries of fate’s subtle breaks. At her age the picture is cloudy, but I pray that one day she will get it.

Three years after Ken Atkins died, I arrived one morning to find the phone in my office blinking. I had to replay the message twice before I realized what the caller was saying. She apologized for the randomness but had only just obtained her father’s medical records and come across my name. I mean, he was my father, but I never got to meet him. I’m trying to piece things together. I was wondering if you remember… I think you were one of the last ones to see him.

I listened once more to make sure I had gotten the number right. Then I checked the name against a catalog of obituaries I keep, to make sure I was not misremembering. I spent a few more minutes dawdling before I finally picked up the receiver and dialed Ken’s daughter. I took a deep breath and tried to do him justice.

GAETAN SGRO is an Academic Hospitalist at the VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System and Clinical Assistant Professor of Medicine at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine. His writing has appeared in The Bellevue Literary Review, Hektoen International, Annals of Internal Medicine, JAMA, and other fine publications. He was selected by National Book Award-winning poet, Mary Szybist, for publication in the Best New Poets 2016 anthology.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 11, Issue 3 – Summer 2019

Winter 2019 | Sections | War & Veterans

Leave a Reply