Sam Shuster

Woodbridge, Suffolk

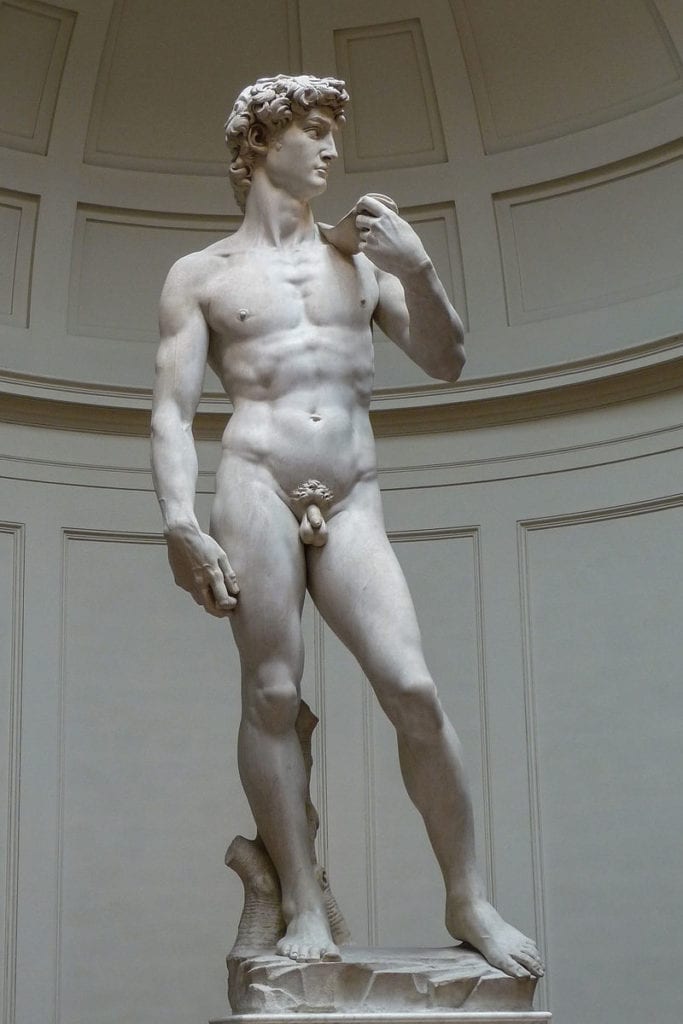

It is impossible to see Michelangelo’s David without marvelling at the way its power and humanity have been fashioned from coarse stone. Apart from its living warmth, there is a unique display of human anatomy, each feature of which stands out in perfection, and together make an image that can be looked at again and again and yet remain fresh. But despite this, there are two anatomical features to which, sooner or later, I return; and both provoke consistently different responses. I first note how David’s right arm, as it comes to rest by his thigh, seems to be an inch, if not an European 2.5 cm, beyond perfection. Then, having re-affirmed my linear bias, I return again to my admiration of this magnificent sculpture, until I rediscover the second recurring visual problem: David is uncircumcised.

How can such a minor thing distract from the feeling evoked by such a great work of art? Unlike my first response, this second is not one of feeling; it is factual. I cannot help but object that a Jew, and not an ordinary man-in-the-street Jew (as I was long, long ago, before I began worshiping at the altar of Atheism), but a Royal Jew, a senior role-model of a Jew, could sport an untrimmed penis. Impossible! And so, whenever I see this magnificent work of art, I am compelled tangentially by a need to try to find an explanation of this apparent impossibility. Of course, it is inconceivable that Michelangelo believed that the Royal David of the Hebrew Bible, the original of his sculpted representation, was uncircumcised, albeit that part may have been modelled from one of the master’s friends. He would have known that Hebrew boys were always circumcised, if only from the many paintings of The Circumcision. So why, then, did he sculpt David incorrectly—unrealistically, with a full penile glory? Those very paintings give the answer.

I have looked at many paintings of The Circumcision in galleries around the world, as will have readers of this essay. But, I ask, just look again, and you will see that the scene is always of The Circumcision, never a circumcision; the preparation of the act is shown, but never its consequences. Now look again at the many paintings of The Madonna and Child, and see if you can find a single image that would confirm that the infant Christ had been circumcised; some may be of the Christ Child before his circumcision on the eighth day, but many, if not most, show Mary holding the child Jesus when old enough to sit upright and hold and play with surrounding objects. No, the paintings of Christ’s childhood never show him circumcised, even though, as with Michelangelo’s David, everyone knew him to have been circumcised.

The universality of this anatomical exclusion, in paintings made independently by many different artists over many years, excludes coincidence. It is therefore inescapable, that at the time these great works of art were made, religious and biblical characters were deliberately not shown to be circumcised, even though they were known to have been. There was, in effect, an aesthetic ban on the showing of circumcision in religious art. That ban operated silently in many different nations, and the only organization with the power and capability to initiate and maintain that international ban was the Church. Evidently that powerful organization saw good reason for this.

That reason has a long story, and it begins with Saint Paul’s striking rejection of the Abrahamic covenant on the regional tribal and prophylactic practice of circumcision. This was a powerful political move, as in one stroke it severed off and distinguished the new religious group. But what followed centuries later in religious art went far beyond this: Paul’s rejection of a universal Jewish practice became a continuous concealment; circumcision was brushed out by artists. Thus, at a time when many of the great religious works of art were created and Bible stories were still being told visually, some were untrue in parts; worse still, their creators must have known them to be untrue. So what was the purpose of this distortion of the truth?

The history of dislike, if not hatred, of Jews is little shorter than their practice of circumcision, and just as universal; yet, it was maintained by people who accepted the Jewish Old Testament and its stories as an essential part of the religious creed of Christianity. This stark contradiction would have made it difficult to confront the fact that biblical heroes such as David were Jewish, and visibly bore the Jewish hallmark of circumcision, as did Jesus, the son of the religion’s godhead. Much easier not to show it or, better still, pretend its troublesome precursor was never removed. If the anatomical hallmark of Jewishness ceased to exist, it would be much easier to distance Jewish heroes and figures of worship from their Jewishness, and to distance Christianity from its parent religion.

Art was a major contributor to this move from St. Paul’s rejection of circumcision to the pretense that it never happened. And this pretense was made real by repetition: our evolutionary past taught us that what we saw repeatedly in the natural world must be true; and, because of that ingrained lesson, so it must have seemed were the artistic creations of the new “natural world,” which disguised or concealed circumcision. This deliberate, repeated fabrication succeeded in the past, much as the internet’s “alternative facts” and “fake news” does in the present. With circumcision erased, the Jewish hero David lost his Jewish hallmark, and could be celebrated by people who rejected all things Jewish.

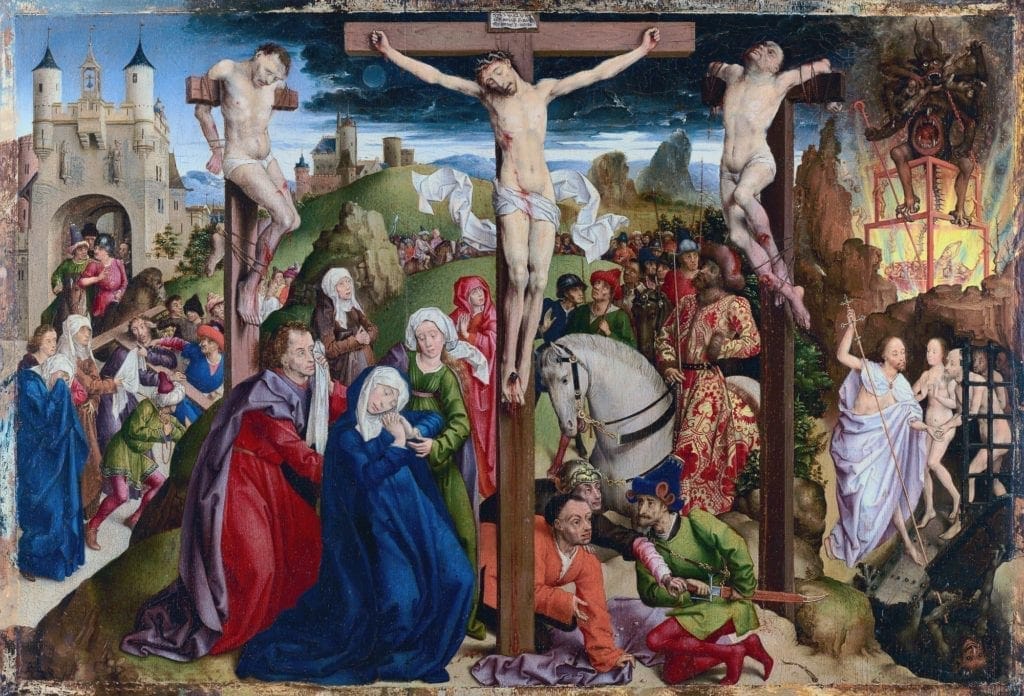

But even if a tacit antisemitism, and a need to dissociate Christianity from its parent source, was the origin of the artistic exclusion of the peculiar Jewish feature known by an anatomical absence, it does not follow that its continued visual exclusion was a deliberate, aesthetic demonstration of that antagonism. David’s foreskin is not a putative measure of his creator’s antisemitism; nor is it credible that all of the many artists who maintained this anatomical subterfuge were actively anti-Semitic. Obedience to a silent ecclesiastical power may have ensured the initial artistic concealment of circumcision, but the subsequent widespread use by artists was a quite different mechanism: it became the norm by the neutral, passive process of usage, a formulaic process in which the presentation becomes an essential part of the story’s content, a phenomenon well shown by paintings of the crucifixion.

The propagandist function of religious art is apparent even in the crucifixion, the most profound story of the holy family. The many paintings of it differ enormously in detail, but almost all, from the very earliest up until the eighteenth century, have the same format: Christ is nailed to the cross horrifically, but his agony is always presented with composure and restraint, as he suffers for us, not for himself; and essential to this is the anatomical contrast with the broken-limbed, chaotic positioning of the thief on each side. Christ’s head droops downwards to the right, where Mary is always to be found; his legs are crossed, usually right over left, and his chest wound varies little. This stylized form was repeated in paintings made across the centuries; it follows no religious text; it is simply an artistic style (differing from sculpture, which often puts Christ’s feet on a plinth for support); a formulaic framework in which the anatomical presentation is critical and rigidly maintained so that the image became the reality. And so it happened with circumcision; the artist concealed it because that had become the style, and the style carried the religious message, not the artist, and this stylized repetitive use of the medium was the key to the acceptance of its message. It is common that a new style of painting or piece of music, dismissed at first sight or hearing, becomes addictive with repetition. Similarly, what began as an item of the religious politics of antisemitism, appears to have continued as an unconscious habit, a passive tradition, devoid of intellectual, emotional, or devotional content; a formulaic fashion. The male extremity of the infant Christ and the adult David came to be shown intact, not for its religious point, but simply because the foreshortened Jewish variety had been brushed out of existence by the habit of not showing it.

In the past, images were important for the maintenance of religious belief; thus the stylized presentation of the Crucifixion served to separate Christ from those for whom he was suffering, and hiding the mark of Jewishness on the child Christ and the adult David helped conceal the relationship of Christianity to Judaism. Of course, those needs have long gone, and what once masqueraded as realism seems unreal to the contemporary eye, fashioned by a quantal realism. That may not be a disadvantage; we have lost the original politicized purpose of the images, but are left with their intrinsic beauty. So although my speculations about how the artistic presentations of practitioners of one religion served to conceal a universal practice of its parent religion are rekindled each time I see Michelangelo’s superlative David, that speculative puzzle is soon dwarfed by the sheer beauty of the image that provoked it; indeed, I would be deeply disturbed if David’s arm was the length I think it should have been.

SAM SHUSTER is an Emeritus Professor of Dermatology, University of Newcastle upon Tyne. He has published over 500 peer-refereed papers and several textbooks, and was a member of Policy and Executive Boards of many learned societies and government committees. He continues research and writing in his retirement.

Acknowledgment

I am most grateful to Bobbie Shuster, a painter, with whom, over many years, I have discussed the observations and ideas in this essay.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 11, Issue 4 – Fall 2019

3 responses

Similarly, the oft depiction of Christ as a blond-haired blue-eyed Anglo Saxon has developed a ubiquitous image in the psyche of many, creating a stumbling block for those that find such objectionable.

The foreskin of the David statue is problematical. It is present but it is NOT a long foreskin.

The circumcision practiced by Jews today is not the circumcision that was done in David’s time.

The second part of the procedure, the periah, was introduced in the Second Century to prevent Jews from appearing as Greek.

https://en.intactiwiki.org/wiki/Periah

Some believe that the short foreskin of the David statue depicts the minimal circumcision that was done in his day.

First, thank you Sam Shuster for the excellent article on the subject.

However, from the other respondents and from many who post on the internet the idea that circumcision is not performed in Jesus or David’s times as it is done today I find to be problematic. Where did that information come from? What is the proof? And is that reliable?

Then there is the problem of Michelangelo knowing that fact centuries later and without the internet to look it up. He would only have had the Jews of his time to see reality.

I think that the most reliable answer to why middle ages and renaissance painters and sculptors did not seek to be reliable even though they would have known what a circumcision looked like was money. They had to sell that art. Whether they were prejudiced or not does not matter. They knew that their buyers were.

So they had to give the public what they wanted or face censure.