Charles VIII was proclaimed king of France in 1470 at the age of thirteen and is remembered in history chiefly for invading Italy to assert his claim to the throne of Naples. He set in motion, by this invasion, a process that left Italy languishing under foreign domination for more than 300 years. During his minority he had been controlled by his conservative and prudent sister, but once in charge he developed ambitious plans to conquer Naples and, by its possession, have rights to the title of King of Jerusalem and to free the Holy Land from the domination of the Ottoman Turks. He had at his disposal an army of 25,000 men, the largest and best equipped in Europe, vastly superior to the mercenary forces with which the Italian city states would fight one another. Reaching Florence he assumed the pose of a conqueror, wearing gilt armor and a crown, and carrying his lance as commanders did when they entered a vanquished city:

“He rode under a splendid canopy held over his head by four knights, his generals on either side of him. Behind him followed the hundred-strong magnificently clothed royal bodyguard; then came two hundred knights on foot. These were followed by the King’s Swiss guards, the men armed with steel halberts, the officers in helmets surrounded by thick plumes. Five thousand Gascon infantry and five thousand Swiss infantry marched in front . . . Behind these came four thousand Breton archers and two thousand crossbow men. The artillery was drawn by horses not by oxen or mules, a sight no Florentine had ever seen before. The cuirassiers presented a hideous appearance, with the horses looking like monsters because their ears and tails were cut quite short. Then came the archers, extraordinary tall men from Scotland and other northern countries, and they looked more like wild beasts than men.”1

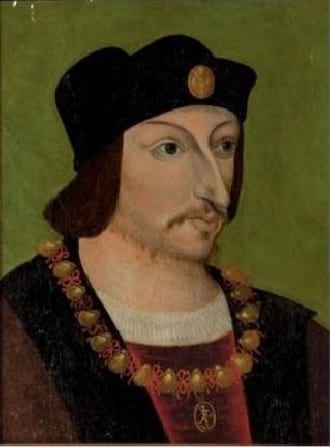

Never before had the Florentines beheld such an imposing army, and the crowds stood in awe at its might. But the cheers subsided as they noticed with a shock how very small the King was, how jerky in his movements,1 with a tremor in his right hand and perhaps a right foot drop.

“He was very small, short-sighted and distressingly ugly with a nose even larger and more hooked than Savonarola’s and with thick, fleshy lips constantly open though partially concealed by wisps of a scattering, reddish beard. His hands and feet twitched convulsively; the few words than ever escaped him were muttered rather than spoken; he walked with a crouch and a limp; his feet was so big that he was rumored to have a sixth toe; he was notoriously gluttonous and lecherous; he was appallingly ill-educated.”1

“In person Charles VIII was far from charming; he was short and badly built; he had an enormous head; great, blank looking eyes; an aquiline nose bigger and thicker than was becoming; thick lips, too, and everlasting open; nervous twitchings disagreeable to see; and slow speech.”2

Charles continued his march through Italy, passed through Rome, and reached Naples unopposed in what has been called a military promenade (1495).

In Naples he lingered for two months in the enjoyment of its seductive climate and scenery. The climate, the country, and the customs of Naples charmed him. He delighted in the gardens and compared them to an earthly paradise, beautiful, and full of nice and curious things.1 But this army, rightly or wrongly, also stands accused of allegedly spreading of syphilis to Italy, and from there to the rest of Europe. For many years syphilis was called “the French disease”—although, to be fair, the French called it “la maladie Anglaise” or “the English disease.”4

When at last Charles decided to return to France, he found his passage blocked by a Holy Alliance of the Italian states, the Papacy, and the Holy Roman Empire. The major battle took place at Fornovo; the outcome of the battle was indecisive, both sides claiming victory, but Charles was able to cross with most of his army back into France. For three years he planned another invasion of Italy, living in his Chateau of Amboise.

He had the reputation of being an excellent player of the paume game (the French ancestor of tennis). One day, wanting to cheer up his wife the Queen who had just delivered a stillborn infant, he invited her to accompany him to watch the game.

“On April 7th, being the eve of Palm Sunday, [he] took his queen by the hand and led her out of the chamber to a place where she had never been before, to see others play at jeu de paume in the castle ditch. They entered into the Haquelebac Gallery . . . known as the nastiest corner of the castle, crumbling at its entrance, and everyone did piss there that would. The king, though not a tall man, knocked his head [on the door frame] as he entered.” (Phillipe de Commines)

Slightly woozy, he watched the game and conversed with people from the court as he usually did but suddenly fell to the floor. His attendants ran to help him, but he did not answer and became unresponsive. The royal doctors were summoned and insisted he not be moved. They worked for nine hours trying to save him, applying the usual treatments used at the time, bleeding and praying.

“It was around two [PM] when he collapsed and he lay motionless until eleven at night . . . The king was laid upon a crude bed and he never left it until he died, which was nine hours later . . . Thus died that great and powerful monarch, in a sordid and filthy place.” (ibid)

The cause of death has been disputed, and as is usual in such cases there have been rumors of a conspiracy, also of poisoning. It has also been suggested, with little evidence, that he had been in bad health and collapsed from some disease. But the consensus remains that he died from a cerebral bleed sustained from the trauma of hitting his head. Such bleeding can occur between the cranium and the dura matter (epidural hemorrhage) or under the dura, between it and the brain (subdural hemorrhage). Both kinds can be immediately fatal, or consciousness can be lost after a latent period. Less severe trauma could also result in bleeding if there were underlying predisposing causes, such as anticoagulant therapy, but no such causes have been shown to have been present in the King’s case, and he likely just died from the violence of the impact.

Charles VIII was succeeded by the Duke of Orleans, Louis XII, called the Spider, who resumed his project of bringing Italy under his sway and again invaded Northern Italy.

References:

- Christopher Hibbert : The rise and fall of the house of Medici, Penguin Books, 1974.

- Francois Guizot :A popular history of France. Volume 3.

- Andrew [email protected] or [email protected]

- Bert O. States, Jon Arrizabalaga, John Henderson, Roger Kenneth French: The Great Pox: The French Disease in Renaissance Europe. Yale University Press

Leave a Reply