Moustapha Abousamra

Ventura, California, United States

|

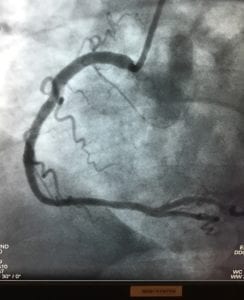

| Author’s right coronary artery before stenting |

“Physician, heal thyself” is a biblical reminder (Luke 4:23) that while physicians are eager and able to heal illness in others, they are often unable to heal themselves. A similar saying, “The cobbler’s children have no shoes,” was mentioned in the Oxford Dictionary as early as 1546, demonstrating that this is not a new phenomenon.

I have always considered myself to be healthy. I have my own physician, whom I see regularly, and I usually follow his advice. I had never been perfect, of course: I knew I should lose weight and exercise more but if I compared myself to most Americans, and even to many American physicians, I felt I was in good shape. I had run sixteen marathons, after all, and I still hoped to run at least one more.

In August 2016, I started experiencing occasional tightness in my chest, usually after a meal. I promptly “diagnosed” this irksome symptom as indigestion and treated it myself. As the tightness increased in frequency, I thought about additional strategies to improve my diet. I had a demanding summer schedule planned, not just at work, but also upcoming trips to visit friends and family, which I figured would give me a chance to exercise more and lose a little weight. The problem would be solved.

I was successful in keeping up with my schedule, but my symptoms did not improve.

The “indigestion” was happening more frequently, not only after meals, but always and alarmingly when I walked or climbed stairs. Oh well, I thought, I am just really out of shape and must lose these extra pounds. It occurred to me that the “indigestion” could be angina, but I concluded that it was most likely nothing more than what is described as “atypical chest pain” since it did not radiate to my arms and was not associated with other symptoms described in “typical” angina.

In mid-September I learned that one of my friends, himself a neurosurgeon, had undergone emergency coronary bypass surgery; he had also been experiencing “atypical” chest pain. I decided that I should tell my physician and make sure that my symptoms were not angina, but first I had to check my schedule. It was packed with obligations to patients, family, and friends for the next six weeks. Since I already had a routine follow up appointment scheduled for November, I decided to just wait.

While I waited, I ignored my own risk factors for heart disease. My father had his first angina attack when he was forty-seven. But, I figured, he had been a smoker; I was not. He died of a coronary event at age seventy-two; I was sixty-nine. My mother also had coronary bypass surgery late in her life; but, I reminded myself, she had radiation therapy to her chest for breast cancer before that, so it was not typical atherosclerotic coronary disease. Both of my parents were hypertensive and so was I, but my own blood pressure had been well controlled on medication. I also had a new diagnosis of type II diabetes mellitus, but again, that was surely just because of those few pounds that needed shedding. And of course there was the hyperlipidemia that I had struggled with for many years, but I had been on statins and my numbers had been good lately. I was careful with my diet; that occasional cheeseburger was probably okay.

|

| Author’s right coronary artery after stenting |

As my symptoms escalated, I had to cut down on walking. I continued to climb stairs at the hospital, a habit I acquired in my running days, but I had to stop and rest every few steps because of shortness of breath. When I finally saw my physician, he was convinced that I was suffering from unstable angina and arranged for me to consult with a cardiologist that very afternoon. The cardiologist agreed, saw no point in doing a stress test since I would obviously fail it, and recommended a coronary angiogram as soon as possible. I agreed to the angiogram but did not want to reschedule the many patient visits and operations that were already planned. I did not want to disappoint my patients. I asked to schedule the angiogram several days later, and while my cardiologist honored my request, he objected to my reasons. I finished my surgeries safely, but continued to have more episodes of “chest tightness” each day.

The procedure was uneventful and successful. My right coronary artery was almost completely occluded. My left anterior descending artery was 80% narrowed. Both needed treatment, and luckily both were amenable to stenting. Two stents were deployed and my chest felt lighter immediately. I felt younger and running again even crossed my mind. But first, I realized how stupid I had been … what if I had dropped dead like my father?

Why had I ignored these potentially serious symptoms? Why do physicians often ignore or minimize symptoms they would treat in patients and do not heed the advice they give to others? For me, there were several reasons. It was inconvenient for me to accept that my symptoms were real, because if I did, I would actually have to deal with them. This “little” chest pain would interfere with my normal patterns and orderly life. Like many surgeons, I also had a sense of invincibility: this could not possibly happen to me.

My role as a surgeon is to take care of patients and their emergencies; it is unnatural for me to be in a role other than a caregiver. I also did not want to disappoint my patients, family, and friends. I had obligations and I always fulfill my obligations. And finally, I tend to have a fatalistic approach to life that I always blamed on my upbringing, where predestination played a major role.

But I am not the only physician who has ever ignored symptoms. I did not realize that I was actually attempting to diagnose and treat myself. In reality, there could be no excuse: I was at once stupid and selfish. I would have never allowed any of my patients to do what I did. I had not told my wife, family members, or colleagues about any of my symptoms. What if something bad had actually happened to me, catching them off guard?

There have been studies about physicians who do not heed their own advice. There are physicians who smoke, some have terrible diets and are significantly obese, many do not exercise, others use tanning beds excessively. At the same time, they advise their patients to stop smoking, eat better, lose weight, exercise, and use sunscreen. Other studies demonstrate that most physicians ignore symptoms of a cold or flu, even though they know that coming to work may spread their illness. They do not want to disappoint patients or colleagues. Medical training also teaches physicians to be stoic and always available to others who need them.

But how often do physicians ignore their own potentially serious symptoms? Is it more common in certain personality types, specialties, or by gender? There is very little information available to answer these questions. At the very least we should be talking about it.

As physicians we must pay attention to our own warning signs, symptoms, and health. We need to discuss these things with our physicians and let them decide what is serious and what is not, rather than attempting to diagnose and treat ourselves. Perhaps our own best advice should be to heed the words of Sir William Osler: “A physician who treats himself has a fool for a patient.”

MOUSTAPHA ABOUSAMRA, MD, was in private practice of neurological surgery in Ventura, CA from 1981-2017. He received his training at the University of Texas Health Science Center in San Antonio, Texas. He is board certified in Neurological Surgery. He served as president of the Ventura County Medical Association, The California Association of Neurological Surgeons, The Western Neurosurgical Society, The Neurosurgical Society of America and as Vice President of the American Association of Neurological Surgeons. He is presently serving as the chairman of California Medical Association’s Council on Ethics Judicial and Legislative Affairs. He and his wife enjoy traveling.

Winter 2019 | Sections | Doctors, Patients, & Diseases

Leave a Reply