James L. Franklin

Chicago, Illinois, United States

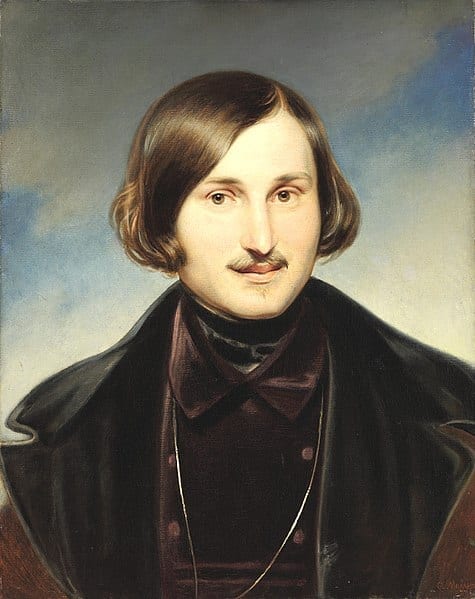

Nikolai Gogol

Nikolai Vasilievich Gogol (1809–1852) was a member of the first wave of great Russian authors of the nineteenth century. Born in a Ukrainian Cossack village then part of the Russian Empire, he made his way to Saint Petersburg where he found his métier in the short story; a genre he pursued throughout his literary career. In his most famous stories, Nevsky Prospect, Diary of a Madman, The Nose, and The Overcoat, he captures a vivid portrait of life in the capital of the Russian Empire. Equally important is his novel Dead Souls and his play The Inspector General. His influence on Russian literature was immense, as Dostoyevsky famously observed, “We all emerged from under Gogol’s Overcoat.”

The Diary of a Madman was originally published in 1835 under the title of Arabesques in what Gogol called a “mishmash” of articles and stories including Nevsky Prospect and The Portrait. The story may have been a response to Prince V. F. Odoyevsky’s story-cycle “The Mad house.” Gogol may also have been influenced by a series of articles about Russian asylums that appeared in the prominent literary journal The Northern Bee.

The story is a series of diary entries that begin on “October 3” written in the first-person by a clerk, Akenty Ivanovich Poprishchin, who works in a government office. The narrator’s descent into madness is reflected in the diary entries that become progressively more obscure; e.g., “2000 A.D., April 43,” and “Martober 86 between day and night.”

We learn that the clerk, in his forties, is an underachiever who resents the head of his section, who prides himself in that he sharpens the quills for the pens for his Excellency in the director’s room, and falls in love with his daughter. He believes he can understand the conversation between her dog and the dog of one of the daughter’s friends. He goes so far as to steal and read the contents of letters written between the animals. From these letters he learns that his beloved is going to marry a captain and that she laughs at the clerk who comes to sharpen her father’s pens.

Diary of a Madman

This crisis precipitates a steep decline as he stops going into work. When he reads in the papers about a succession problem in Spain and comes to believe he is King Ferdinand the Eighth, he is called into work and compelled to sign resignation papers.

Finally, he believes he is taken to Spain but it is clear it is an asylum where his head is shaved and he is beaten. The dates on the diary entry become unintelligible. In the final diary entry, he has a vision of being taken up to heaven and he sees his mother and cries out to her.

Gogol’s story has been cited in the psychiatric literature as being one of the oldest and most complete descriptions of schizophrenia and useful in teaching students to identify the symptoms of mental illness. Eric Lewis Altschuler has discussed this story in an article in the British Medical Journal as fulfilling the diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia as outlined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV.1 While modern descriptions of schizophrenia begin with Kraepelin’s work on dementia precox in 1898, Gogol’s story gives credence that schizophrenia is an old disease, and Altschuler reviews the possible explanations for the dearth of reported cases prior to Kraeplin’s discription. Nigel M. Bark, in a 1985 issue of the British Journal of Psychiatry, examines the case of Poor Mad Tom in Shakespeare’s King Lear as a literary example of the disease appearing before 1800.2 Gogol’s initial title for this story was “The Diary of a Mad Musician” and reflects the influence of the German author E.T. A. Hoffman and his character, Kapellmeister Kriesler. Altschuler cites Gogol’s story and additional evidence that schizophrenia was widely disseminated in Europe early in the nineteenth century.

In his final year, Gogol himself manifested features of mental illness, which included religious mania, including a pilgrimage to Jerusalem in 1848, and a depressive stupor during which he burned most of the manuscript for a second part of Dead Souls on February 24, 1852. Refusing all food and water, he died nine days later.

References

- Eric Lewin Altschuler, One of the oldest cases of schizophrenia in Gogol’s Diary of a Madman, British Medical Journal, 323, 1475-1477, December 2011

- Nigel M. Bark, Did Shakespeare know Schizophrenia: The Case of Poor Mad Tom in King Lear, British Journal of Psychiatry, 146, 436-438, 1985

JAMES L. FRANKLIN is a gastroenterologist and associate professor emeritus at Rush University Medical Center. He also serves on the editorial board of Hektoen International and as the president of Hektoen’s Society of Medical History & Humanities.

Leave a Reply