James L. Franklin

Chicago, Illinois, United States

|

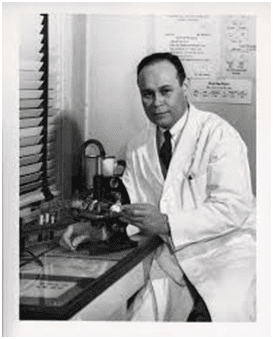

| Charles R. Drew, 1904 |

“My point is, if you have a course on health and whatever, then you do know Dr. Charles Drew. You’ve heard of him?”

“No.”

“Shame on you, Mr. Zukerman. I’ll tell you in a minute” . . .

“You haven’t told me who Dr. Charles Drew was.”

“Dr. Charles Drew,” she told me, “discovered how to prevent blood from clotting so it could be banked. Then he was injured in an automobile accident and the hospital that was nearest would not take colored, and he died by bleeding to death.” 1

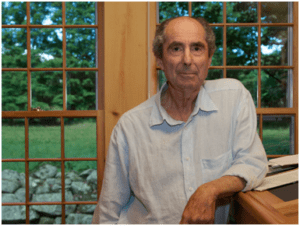

Is that really correct? The above quotation appears toward the end of the late Philip Roth’s great novel, The Human Stain. The novel is the story of Coleman Silk, a fictitious character of Roth’s creation, born into a black family from East Orange, New Jersey. As a young man Silk learns to pass himself as Caucasian and enlists in WWII as a white soldier. He continued this deception throughout his life. He successfully passes himself off as Jewish, becomes a professor in classic literature in a small liberal arts college, marries a Jewish woman, and fathers four children, all of whom grow up ignorant of their father’s true identity. Ironically, he is disgraced and forced to resign his faculty position because he is accused of making a racial slur. He questioned his class as to the identity of two students who had not attended a single class for several weeks—“who are they, spooks?”—unaware that they were African American students. By the end of the novel, Coleman Silk has been killed, in part because he is Jewish, apparently deliberately driven off a road along with his girlfriend, Faunia, by her jealous anti-Semitic ex-husband Farley.

The introductory quotations come from a scene near the end of the novel when Nathan Zuckerman, a frequent “Rothian” narrator who has been telling us Coleman Silk’s life story, meets Silk’s sister Ernestine, an African American woman who shows up unrecognized at Silk’s funeral. It is then that Zuckerman first learns of Silk’s secret identity. In the scene that follows, Ernestine, a teacher, enlightens Zuckerman about her family and her views on racial issues in America, including her disdain for the idea of Black History Month. Hence the question about Dr. Charles Drew and his importance as part of Black History. Ernestine continues to instruct Zuckerman, asserting that one should also know about Matthew Henson. Zuckerman has never heard of him either. She enlightens him by relating that he was first to discover the North Pole, not Robert Peary or Frederick Cook. Matthew Alexander Henson (1866–1950) accompanied Robert Peary on seven voyages to the Arctic. He was part of the 1908–1909 expedition that claimed to have reached the geographic North Pole. Henson believed he was the first of the party to reach the pole. Similarly, when we think about who first climbed Mount Everest it is Sir Edmund Hillary, but history taught us to also remember his Nepalese sherpa, Tenzing Norkay.

|

| Philip Roth |

With regard to the real Dr. Charles Drew, while he made a major contribution to the methods of blood banking at the outbreak of World War II, he did not discover how to prevent blood from clotting. Drew played a major role in organizing the collection, preservation, and transportation of plasma for Britain even before the United States entered World War II. He was a graduate of McGill University School of Medicine and was the first person of African American descent to earn a Doctor of Medicine degree from Columbia University. He was a distinguished medical educator and played a major role in training surgeons at Howard University and Freedmen’s Hospital in Washington, D.C. He was the first African American surgeon to serve as an examiner for the American Board of Surgery.

Drew did die as the result of injuries sustained in a car accident in rural North Carolina while driving along with three other colleagues to attend a mostly black annual medical conference in Tuskegee, Alabama. He was not refused medical treatment or transfusion at a hospital because he was “colored.” A review of the medical treatment he received in the emergency room of the Alamance General Hospital in Burlington, North Carolina, five miles from the site of the accident, was prompt and administered without regard to his race. The white staff physicians administering care were aware of his reputation and did everything they could do to save him. His injuries were too grievous and his condition too unstable to allow transfer to Duke Hospital in Durham some forty-eight miles away.

Charles Drew was of a very light complexion and on occasion was mistaken for Caucasian. His wife verified that if a situation arose where he encountered a person who did not realize he was African American, he would be quick to make his racial identity clear. It is ironic that he makes an appearance in Roth’s The Human Stain whose main character, Coleman Silk, willfully and successfully hid his racial identity.

Roth’s character, Ernestine, is relating myths about Dr. Charles Drew that were prevalent in the black community in America for years after his death in 1950: i.e. that he was refused transfusion and died because he was refused treatment. Philip Roth published The Human Stain in 2000. Two biographical accounts of the life, career, and death of Dr. Charles Drew were in print. The earliest was written by Charles E. Wynes, a 1988 biography, Charles Richard Drew: The Man and the Myth, published by the University of Illinois Press, and the second, Spencie Love’s One Blood: The Death and Resurrection of Charles R. Drew published by The University of North Carolina Press in 1996. It would be surprising if Roth did not know the truth about the medical care that Dr. Charles Drew received after his fatal car accident. The fact that his character Ernestine, an educated black woman and teacher in the Newark school system, believed in this myth tells us something more about race relations in America. The myths were credible in that they were consistent with what members of the black community experienced in the rural southern United States. It is probable that this was what Roth wished to convey.

References

- Philip Roth, The Human Stain, Vintage International, 2001

JAMES L. FRANKLIN is a gastroenterologist and associate professor emeritus at Rush University Medical Center. He also serves on the editorial board of Hektoen International and as the president of Hektoen’s Society of Medical History & Humanities.

Winter 2019 | Sections | Books & Reviews

<div id=”trendmd-suggestions”></div>

Leave a Reply