Nothing exemplifies more the French saying “on revient toujour a son premier amour” (one always returns to one’s first love) than the life of George Stubbs. Already at the age of eight he was sketching animal bones in his father’s tannery in Liverpool. Later, as a teenager, he was dissecting dogs and horses, then decided to become a painter, and throughout his life always returned to his twin passions—anatomy and art, dissecting and painting.

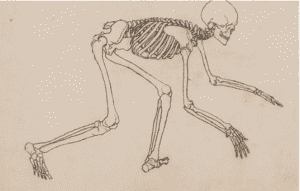

After a very brief apprenticeship with a painter, he spent five years touring northern towns painting portraits. In 1745 he settled in York, where a surgeon gave him the opportunity to dissect cadavers and lecture on anatomy at the hospital. Then he illustrated Dr. John Burton’s “New System of Midwifery,” taking many risks to secure cadavers and dissect them in his attic, even snatching the body of a woman who had died in labor. In 1754 he went to Italy for further study but returned almost immediately, convinced that the best way was to paint from nature.

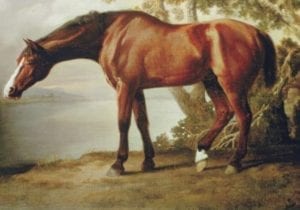

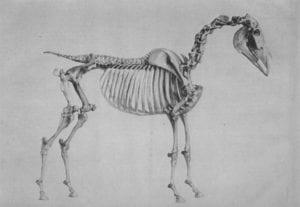

Returning from Italy, he hired an isolated farm-house in the country and began to dissect horses. He bled them by cutting their jugular vein and injected their vessels with tallow. After dissecting a large number of them he published in 1768 the “Anatomy of the Horse,” consisting of twenty-four plates with accompanying the text. The work was successful with the public and also with natural scientists.

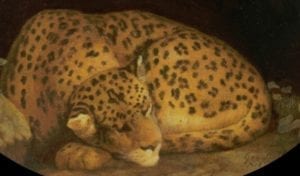

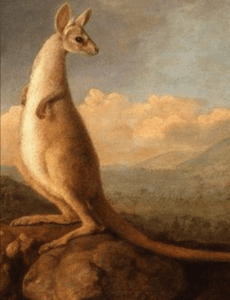

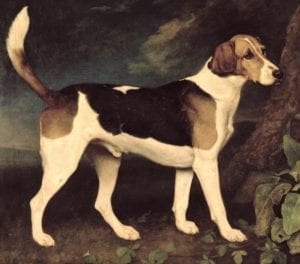

His reputation established, he continued as a painter. Besides anatomical and animal paintings, he produced portraits of duchesses, gentlemen shooting, the Prince of Wales on horseback, and figures on enamel for Josiah Wedgwood’s china. He painted for John Hunter’s collection at the Royal College of Surgeons a baboon, a macaque monkey, a rhinoceros, and a yak that Warren Hastings had brought back from India. For William Hunter he painted a moose, an antelope, and a blue bull. In 1768, when Joseph Banks returned from his voyage of discovery to Australia, he painted a kangaroo based on the description of the animal and supplemented by inflating the skin that Banks had brought back with him.

He also painted an accurate representation of a rhinoceros, correcting the distortions and errors of Alfred Dürer’s classical painting of 1515. In London he paid three guineas for a dead tiger and took him home to dissect. Continuing to work until his death in 1806, he painted Tibetan bulls, leopards, buffaloes, common fowls, and birds. His contribution to the world of art was ignored for many years, but he was rediscovered in the middle of the twentieth century. Since then his reputation has steadily grown. He has come to be viewed as more than just a horse painter, a label he regretted during his lifetime. His oeuvre is now exhibited in most of the great art museums of the world; and for anatomists he remains a pioneer and a model of hard work and dedication.1

Further reading

- Fountain RB. George Stubbs (1724-1806) as an anatomist. Proc. R. Soc. Med. 1968;61:639 (July 1968).

Addendum

A recent acquisition by the Kimbell Museum of Art in Fort Worth Texas illustrates with perfection the mastery of George Stubbs as painter of horses. Titled Mares and Foals Belonging to the Second Viscount of Bolingbroke, the sheer size of the painting—40” high x 74” wide—strikes a bold impression. Stubbs imbued his painting with more than anatomical acuity. As expressed so eloquently by Willard Spigelman, Stubbs created “an equine family portrait,” and delivered “a tender study of equine Madonnas nurturing their children.” Thus, by his devotion to and mastery of the beloved animal, Stubbs has raised his rendering of the horse to a nearly spiritual level. —Sally Metzler, PhD

Addendum notes

- See: https://kimbellart.org/news-and-stories/kimbell-acquires-masterpiece-george-stubbs

- The Wall Street Journal (Saturday/Sunday, 6/29-30, 2024, p. CI4).

Leave a Reply