Mariel Tishma

Chicago, Illinois, USA

The landscape of Mesopotamia was riddled with challenges, but for every problem that arose there was a deity to petition. Of these perhaps the most well-known was Inanna or Ishtar, who influenced fertility goddesses across cultures.1 But when it came to issues of health, the people were more likely to turn to Gula.

First known as Bau, Gula emerged as a Sumerian deity of the dog and of “’increase’ . . . of ‘plenty’ . . . of vegetation . . . and of human generation.”2 It is not clear at what point Bau became a goddess of healing, but from 2000 BCE onward,3 Bau and Gula were conflated. As one of Bau’s symbols was the dog, and Gula’s name was interpreted as “great in healing,”4 the dog became a symbol of medicine in the Mesopotamian pantheon. This was supported by observational evidence (and suggests Bau may have been healing before Gula came along) as legend noted how a dog’s wound seemed to heal faster after the dog licked it.5,6

Gula often appeared not only with her dogs but also carrying “a sickle-shaped tool . . . a scalpel used for surgery.” 7,8 Medical knowledge was considered a gift given through Gula, and it was believed that physicians visited her temple to train before practicing medicine. There they worked with fellow physicians and the dogs who participated in healing rituals.9

Gula was the primary but not only deity associated with dogs and healing. She was the “the supreme healer”10 but her son Damu was seen as a sort of intermediary who brought her power to doctors. Thus the two were often appealed to together.11 Moreover, Gula (and Bau) could be associated with or alternately named as at least four other goddesses in Mesopotamian tradition: Ninisinna, Ninkarrak, Nintinugga, and Baba.12

Inanna – the goddess associated with love, fertility, and war – was often attended by a pack of hunting hounds. Sometimes, Inanna and Gula were pictured together, sharing symbols and roles. In fact, by the middle of the first millennium, “Ishtar appropriated the healing properties of Gula,”13 and around that time Gula fell into obscurity.

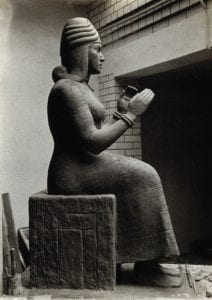

Musée du Louvre. Photo by Marie-Lan Nguyen on Wikimedia. CC BY 2.5.

Dogs in Mesopotamia were highly respected,14 and Mesopotamia was one of the few cultures to associate dogs with healing. Elsewhere, dogs in myth tended to be psychopomps, not healers, instead aiding the dead in finding the afterlife. This echoes the journey of domestication. Dogs transformed from wild to tame, so they were believed to move “between the planes of existence” the same way they could move “between the worlds of animals and humankind.”15 Some examples of this are the Egyptian Anubis, judge of the spirits of the dead, and the Greek Cerberus, who guarded the underworld. Mesoamerican cultures also imagined the dog as an underworld guide. The Maya believed dogs “help the deceased through the challenges presented by . . . [the underworld] and to reach paradise.”16 The Aztec god of death, Xolotl, was represented by a dog and lent part of his name to the hairless Xoloitzcuintli breed, which is still regarded for its healing abilities in some parts of Mexico today.17

Perhaps these beliefs are justified, as some pet owners and professionals believe that dogs can sense when the humans around them are reaching the end of life. Some hospices even use a dog’s behavior as a “sign to tell relatives to come say their goodbyes.”18 But despite their more dire mythological associations, there is also support for the role of dogs in healing. Today, one may take the folk advice to imbibe “a hair of the dog that bit you,” in order to cure a hangover. While there is no medical evidence behind the saying, it began as a belief that after being bitten by a rabid dog, one could be cured of rabies by consuming some of that dog’s hair.19

While dogs cannot cure all ills, and socioeconomic factors cannot be disregarded, some research has shown that people who own dogs tend to be healthier than those who do not.20,21 Pets keep their humans focused on the present, allowing them to “be more distracted from their illness.”22 Other research has begun to explore whether dogs could be “early warning systems”23 for certain illnesses. Some already are, such as service dogs that are used to signal and manage conditions like low blood sugar, seizures, and panic attacks. Dogs in hospitals have provided psychological benefits for isolated patients.24 In this way, dogs are once again placed in the role of healer, or at least medical aid, in a modern setting.

In addition to recognizing dogs’ healing presence, the Mesopotamians may not have been too far off in appreciating the benefits of wound licking. Wound licking is “an instinctive response”25 in animals, which suggests some benefit to the behavior. Human mouth wounds tend to heal faster and with less scarring than other wounds, perhaps because of the humid environment created by saliva.26 This is reinforced by many studies of the makeup of spit. A protein called Nerve Growth Factor has been observed in saliva, which caused wounds under experimental conditions to heal twice as fast as untreated wounds.27 Saliva also contains other proteins, peptides, histatins, and nitrates, all working together to relieve pain, speed up cell growth, prevent infection, and reduce or inhibit inflammation.28,29

While it may not be wise to spit in every (or any) wound, it appears that dogs may use their saliva as a primitive sort of medicine. The goddess Gula is a representation of this dog medicine and of the lasting tie between dogs, legend, and human health.

It is worth asking what may be learned from these stories. Would people heal more quickly if allowed time with their pet companions? What medicines may already exist in the makeup of our own bodies?

Where can we find room for canine attendants in our healing temples?

References

- Joshua J. Mark, “Inanna,” Ancient History Encyclopedia Limited, published October 15, 2010, accessed November 23, 2018, https://www.ancient.eu/Inanna/.

- J. Dyneley Prince, “A hymn to the Goddess Bau,” The American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literatures, Vol. 24, No. 1 (Oct., 1907), 63, accessed November 23, 2018, https://www.jstor.org/stable/528101.

- Joshua J. Mark, “The Nimrud Dogs,” Ancient History Encyclopedia Limited, published January 12, 2017, accessed November 23, 2018, https://www.ancient.eu/article/1001/the-nimrud-dogs/.

- Joshua J. Mark, “Gula,” Ancient History Encyclopedia Limited, published January 18, 2017, accessed November 23, 2018, https://www.ancient.eu/Gula/.

- Ibid.

- Tallay Ornan, “The Goddess Gula and Her Dog,” IMSA 3 (2004): 18, accessed November 23, 2018, https://www.academia.edu/864981/Tallay_Ornan_2004_The_Goddess_Gula_and_her_Dog_IMSA_3_13-30.

- Barbara Böck, “Gula and Healing Spells” in The Healing Goddess Gula: Towards an Understanding of Ancient Babylonian Medicine, (Leiden, The Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill NV, 2014), 112.

- Tallay Ornan, “The Goddess Gula and Her Dog,” 22-23.

- Joshua J. Mark, “Gula,” https://www.ancient.eu/Gula/.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Kathryn Stevens, “Ninisinna (goddess),” Ancient Mesopotamian Gods and Goddesses, Oracc and the UK Higher Education Academy, last modified April 1, 2016, accessed November 23, 2018, http://oracc.museum.upenn.edu/amgg/listofdeities/ninisinna/index.html.

- Tallay Ornan, “The Goddess Gula and Her Dog,” 26.

- Wolfram von Soden, “Nutrition and Agriculture ” in The Ancient Orient: An Introduction to the Study of the Ancient Near East, Translated by: Donald G. Schley, (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1994), 91.

- Catherine Johns, Dogs: History, Myth, Art, (Harvard University Press, 2008), 83.

- Joshua J. Mark, “Dogs in the Ancient World,” Ancient History Encyclopedia Limited, published June 21, 2014, accessed November 23, 2018, https://www.ancient.eu/article/184/dogs-in-the-ancient-world/.

- “About Xolos,” Xoloitzcuintli Club of America, Inc., published 2013, accessed November 23, 2018, http://www.xoloitzcuintliclubofamerica.org/about_xolos.

- Sue Manning, “Pets sense cues to comfort the sick, dying or grieving,” Chicago Tribune. August 15, 2015.

- “What is the origin of the phrase ‘hair of the dog’?,” Oxford Living Dictionary, Oxford University Press, accessed November 23, 2018, https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/explore/what-is-the-origin-of-the-phrase-hair-of-the-dog/.

- Deborah L. Wells, “Domestic dogs and human health: An overview,” British Journal of Health Psychology, 12, (2007): 152, accessed November 23, 2018, DOI:10.1348/135910706X103284.

- Ibid. 146.

- Lynette A. Hart, “Dogs as human companions: a review of the relationship,” in The Domestic Dog: Its Evolution, Behaviour and Interactions with People, ed. James Serpell, (New York, NY, Cambridge University Press, 1996), 169.

- Deborah L. Wells, “Domestic dogs and human health: An overview,” 147.

- Ibid. 150.

- Stanley Coren, “Can Dogs Help Humans Heal?,” Psychology Today, published June 7, 2011, accessed November 23, 2018, https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/canine-corner/201106/can-dogs-help-humans-heal.

- Henk S. Brand, Enno C. I. Veerman, “Saliva and wound healing,” The Chinese Journal of Dental Research 16, no. 1 (2013): 8, accessed November 23, 2018.

- Stanley Coren, “Can Dogs Help Humans Heal?,” https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/canine-corner/201106/can-dogs-help-humans-heal.

- Ibid.

- Henk S. Brand, Enno C. I. Veerman, “Saliva and wound healing.”

MARIEL TISHMA is a creative writer trying to prove that she really is a successful human being, and not three red squirrels inside a human shaped coat. She currently serves as an Executive Editorial Assistant for Hektoen International. She’s been published in Argot Magazine, Syntax and Salt, The Artifice, and Fickle Muses. She graduated from Columbia College Chicago with a BA in creative writing and a minor in biology. Learn more at marieltishma.com.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 13, Issue 4 – Fall 2021

Leave a Reply