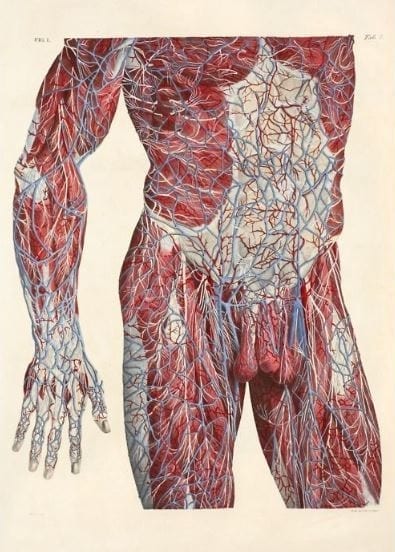

Francesco Carlo Antommarchi (1780–1838) was a man of dubious character who served as Napoleon’s physician on the island of St. Helena from 1818 until his death in 1821. He began his education in Livorno, Italy, then in Pisa and Florence, graduating with a degree in surgery in 1812. For the next six years he practiced neither surgery nor medicine but worked dissecting human cadavers under the well-known Florentine anatomist Paolo Mascagni. When Mascagni died, his surviving family employed Antommarchi to publish his anatomical plates, but the dissatisfied family later ended the agreement and delayed their publication.1,2 On his return from St. Helena, Antommarchi published some of Mascagni’s plates under his own name, claiming in his book The Last Days of Napoleon (1823) that the emperor had admired them and wanted them dedicated to him.1

In 1819 Antommarchi left Florence for St. Helena. Recommended by Napoleon’s mother and an uncle cardinal, he was sent to replace the British physicians whom Napoleon would not accept. In St. Helena he was described as light, talkative, vain, ignorant, and lacking in skill.2 Napoleon was not impressed. He dismissed him from his service several times, only to let him resume his duty soon after. He said of him, “I would give him my horse to dissect, but I would not trust him with the cure of my own foot.”2

When Napoleon died, Antommarchi performed the autopsy. Five British surgeons and physicians were present.3 All agreed that the emperor, like his father, had died from cancer of the stomach. The cancer had extended from the cardiac orifice to within an inch of the pylorus and had made a hole in the stomach wall that was sealed off by the liver. The British doctors thought the liver was normal. Antommarchi disagreed and refused to sign the autopsy report.3

After the emperor’s death Antommarchi claimed to have made an imprint of Napoleon’s face when the English doctors refused or failed to do so.2,4 Later, he tried to make money by issuing a prospectus and inviting subscriptions but was not successful. In 1834 he offered, with great fanfare, a copy of a death mask to the city of New Orleans.1 Various versions exist of this affair, the most widely accepted being that the mask was fashioned by the British physician Francis Burton, purloined in his absence and subsequently passed onto Antommarchi, who in his untrustworthy publication The Last Moments of Napoleon (1823–1826) claimed he had fashioned the mask himself. It appears that he, and also others, made copies from Dr. Burton’s original mask, which explains the presence of several death masks in various museums. There has also been some controversy over an alleged piece of Napoleon’s bowel displayed in the Museum of the Royal College of Surgeons, supposedly taken by Antommarchi from the emperor’s body at the time of the autopsy.2–4

Antommarchi spent the rest of his life in other questionable enterprises.1 In 1831 he went to Poland as general inspector of hospitals, became involved in an uprising against the Russians, and had to flee to Paris to escape the czar’s forces. In 1834 he emigrated to Louisiana, where he disposed of a bronze death mask of Napoleon.1 He briefly worked as physician in Veracruz, Mexico (1834) and then in Santiago de Cuba. There he became adept at performing cataract surgery and died of yellow fever in 1838.1 He has been called the Malvolio of the drama of St. Helena.2

References:

- Lurie SJ. Plate From Plans Anatomies. JAMA 2001;286:1008.

- R.B. Antonio Antommarchi. BMJ, July 28, 1912, p 22.

- The death of Napoleon. BMJ, Dec 28, 1912, p 1661.

- Diary of Napoleon’s undertaker. BMJ, Oct 9, 1915, p 544.

Leave a Reply