Nicolo Paganini, the greatest violin virtuoso ever, was born in the Republic of Genoa in 1782. At age five he learned to play the mandolin and at seven the violin. When his city was invaded by the French Revolutionary Army in 1796, his family fled the city but later returned, and by age eighteen, Paganini had already built a local reputation around Genoa and Parma. By the age of twenty-eight he had become known throughout Europe.

Paganini played the violin as no one had done before. Also possessed of a remarkable memory, he played with such an amazing rapidity that he became known as the “demon,” “devil’s violinist,” or the “witches’ child,” and later was even considered to have been music’s first rock star. Some scholars have postulated that his extraordinary virtuosity was due to his having Marfan’s syndrome, characterized by excessively long limbs and thin fingers, or Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, in which the joints are excessively flexible.

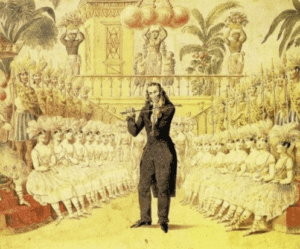

As a youth, Paganini led an extravagant and dissolute life. He was a gambler and a womanizer, eccentric and odd, also ambitious, hyperexcitable, and hyperactive. In 1832 he gave sixty-five concerts in thirty different European cities within three months. He usually played his own compositions, which were highly regarded and often required to be performed at high speed. They included his twenty-four famous Caprices, which later inspired many famous composers to write variations on their themes.

In matters of his health, Paganini has been described as being a veritable museum of pathology. It had been assumed that he had tuberculosis and syphilis, diagnoses that later were questioned. His symptoms began in 1820, when he noted cough, sputum, weight loss, and a hoarse voice. Though attributed at one time to tuberculosis, this diagnosis seems unlikely because he would not have survived for twenty years. A diagnosis of laryngeal syphilis has also not been confirmed, because direct laryngoscopy was not available at that time. It has been suggested that his original cough may have merely been nervous in origin, or due to a trivial illness or to calomel abuse. An unlikely suggestion has been intermittent nerve paralysis due to pressure by an abnormal dilatation of the aortic arch. At various times later in life he was also diagnosed as having a stricture of the esophagus (1834), rectal stenosis (1835), urethral narrowing requiring dilatation with a catheter (1837), and ulceration of the palate (1839).

A plausible suggestion, first made by a medical consultant to the Italian opera in Paris, was that Paganini was the victim of iatrogenic chronic mercury poisoning.1 First prescribed in 1823 under the impression that he had laryngeal syphilis, mercury was given in very large doses, by mouth and by ointment, combined with opium. One consultant wrote that “this medication has had the most disastrous effects on his health,” “attacking his stomach,” and “causing many of the symptoms associated with mercury poisoning.” It resulted in his teeth falling out and forming oral abscesses and osteomyelitis of the jaw. Opium induced constipation would have caused him to take additional mercury in calomel (mercury chloride) as well as large doses of the proprietary Leroy’s purgative and emetic that may have contained additional toxic substances. Mercury poisoning would have caused characteristic increased salivation, deterioration of his eyesight, and tremor of the hands, the hatter’s shakes of the Mad Hatter in Alice in Wonderland. It also would have caused personality changes, so that from being an ebullient personality he became retiring, shy, and even easily startled by noises. He died in Nice in 1840, leaving a fortune of 1.7 million francs and bestowing his violins to eight violinists of first rank.

When Paganini was on his deathbed, he refused last rites, either because he could not speak or because he expected to recover. Because of his “laxity of morals and irreligion,” he was refused absolution and burial in consecrated ground. For the next fifty-six years his corpse underwent incredible adventures, first moved to an abandoned leprosarium, then to a cement vat in an oil factory, buried for four years in a garden in Parma, then in a consecrated cemetery in 1876, then inexplicably exhumed by his son in 1883, and not definitely buried until 1896. At his death the body had been embalmed but no autopsy was done, so the cause of the illness of the greatest violinist the world has ever known remains a mystery.

References

- O’Shea JG. Was Paganini poisoned with mercury? J R Soc Med. 1988;81(10):594-7.

- Violin photos: “Views of the Hubay 1726 Stradivari”. Photos by Eduardo Antico (Bart weisser), 2009, on Wikimedia. CC BY-SA 3.0.

Leave a Reply