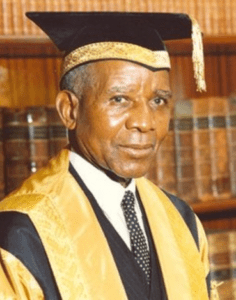

In his 1936 list of Truants in medicine who “deserted medicine” and yet perhaps to his surprise or condescension “triumphed,” Lord Moynihan of Leeds listed mainly successful men of science or letters. Actors and sportsmen, however famous, were not included. But mentioned were several people who “strayed to politics,” notably Clemenceau, Sun Yat Sen, and the unfortunate Dr. Guillotin. To this list we must now add Dr. Hastings Banda of Malawi, formerly Nyasaland. Dr. Banda had been born in 1898 in the former British Central Africa. His tribe lived by subsistence farming and at age four he was given a small piece of land to cultivate with a hoe. At age seven he went to a European style school and was baptized, and later submitted to the severe initiation rites prescribed by his tribe. When debarred from further education, he walked 400 miles to South Africa, went to Johannesburg and worked in the mines. In the shanty town where he lived in he rubbed shoulders with murderers, priests, whores, schoolmasters, housewives, and other migrants like himself from outside South Africa’s borders. He was ordained an African Methodist minister, saved some money, and with some assistance from the church was sent to America to complete his education. He arrived in the United States in July 1925, an amiable African youth with “few friends and two dollars in his pocket.” For three years he studied agriculture, civics, Latin and Spanish at the African Methodist Episcopal Institute in Xenia, Ohio. In 1928, he enrolled as a pre-medical student at Indiana University, and stayed there for two years. He was a quiet, serious student “who always sat in the front row during lectures so as not to miss a word the lecturer said.” He was smart, not unfriendly, but “didn’t have a great of personality” and “did not have much to say.” In 1930 he transferred to the University of Chicago to study history and political science. Graduating after one year and taking a short post-graduate course, he then enrolled at the Meharry Medical College in Tennessee, an African-American institution. There he experienced “naked racialism,” worse than in Ohio or Chicago, and even witnessed a lynching. In 1937, after five years at Meharry, Banda graduated in medicine. As American degrees were not recognized in the British world, he left for Scotland. There he attended the classes and demonstrations of the great surgeons of the day. He also began to visit sick people in poor districts of Edinburgh in order to gain experience and to alleviate suffering. He was caring and took pains to explain to his patients the causes of their illnesses. He was now in his early forties and impressed his Scottish colleagues by his Puritanism, which outstripped even theirs. He was a teetotaler, was scandalized that a Presbyterian city such as Glasgow had so many pubs and that at dances, married men were allowed to hold other men’s wives during ballroom dancing. Colleagues were also impressed by his austere fastidiousness. In restaurants, when he took meals, he would carry a small hand-held towel which he used in preference to that provided in their washroom. But he was noted for his sense of humor and was friendly. After obtaining his degrees in Edinburgh he tried unsuccessfully to enter the service of the Nyasaland government; he was told that if hired, as part of his condition of employment, he would have had to refrain from seeking contact with white doctors. In 1941 he moved to Liverpool and established a practice which flourished, and while many of his patients were so poor that he waived the fee, he also had some wealthy patrons. In 1942, during World War II, he was conscripted as an army doctor but being a conscientious objector was forced to move to Newcastle. There he worked at the mission for foreign seamen and later at the hospital. He had maintained his Puritanism and was shocked by the relaxation of mores and by the many girls who would approach doctors to have their unwanted pregnancy terminated. By 1944 he was allowed to leave Newcastle and briefly worked in North Shields, but two months after the end of the war he moved to London and set up a national health service practice in the suburb of Harlesden. His confidence grew and his reserve diminished. He became known as a man of great personal charm, which had the effect of moderating his Puritanism but made him more authoritative and even dogmatic. By the time he turned fifty he had become a typical British general practitioner. He bought a house in a fashionable district, drove a small car, invested in the stock market, became a freemason, and took to wearing a black homburg and carrying a rolled umbrella. He was highly respected as a doctor and esteemed in his community. But despite his Englishness, he also became aware of the momentous changes taking place in his native Nyasaland.

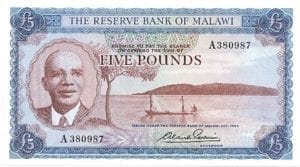

In London he had met some of the African activist leaders, such as Jomo Kenyatta and Kwame Nkrumah, and had become more interested in African politics. It was at about this time that Britain was planning to develop a federation between Nyasaland, Northern Rhodesia, and Southern Rhodesia, and many Africans feared that such a union would be dominated by the whites of Southern Rhodesia. Most of the Africans from his native Nyasaland were definitely opposed to federation. By 1945 Banda had become involved in lobbying for his county’s independence, advising and providing financial support; but in 1951 he moved to Ghana, perhaps because of the scandal of an affair with his receptionist. In 1958, after various political negotiations, he finally returned to Nyasaland after an absence of forty-two years. Acclaimed a savior of his own land, he began touring the country to speak against colonialism and against the planned federation and was briefly imprisoned in 1961. But events moved quickly and in 1963 he was formally appointed prime minister of Nyasaland, which one year later became the independent republic of Malawi with him as president. What followed is a story all too often seen in our time, especially in Africa. Very soon Banda consolidated his power, declared Malawi a one-party state, and proclaimed himself president for life. No criticism or opposition was tolerated. Opponents were arrested, exiled, imprisoned and tortured or killed. According to one estimate, as many as 18,000 people were killed during his rule. All adult citizens were required to become members of the ruling political party and young men pioneers were recruited to intimidate and harass the public. Banda became the subject of an extensive cult of personality and all business buildings had to have a picture of him hanging on the wall. When he visited the city a contingent of women would greet him at the airport and dance for him. Rigid censorship was instituted, history was rewritten, and books of some dissident tribes were burned. Banda improved the country’s infrastructure and educational system. He followed a policy of non-alignment and even maintained friendly relations with South Africa at a time of world-wide outcry against apartheid. He refused to have diplomatic relations with the communist governments of Eastern Europe or Asia; advocated pan-Africanism; supported the United States during the Vietnam War; established diplomatic relations with South Africa and even concluded a trade treaty with that country. To promote the Malawian economy he adopted a policy of forced industrialization. Like other dictators from that era, he accumulated large amounts of money in personal assets, estimated at US $320 million. The Puritanism from his earlier life reasserting itself, he instituted a rigid conservative dress code for women, who were not allowed to wear short skirts, trousers, or see-through clothing. Men had to wear short hair, foreign visitors were given mandatory haircuts at the airport, and even foreigners coming to Malawi were subjected to the dress code, not permitted to enter the country if they wore short dresses or trousers. Hippies and men with long hair were denied entry. Things changed at the end of the Cold War when Banda was expected to institute more transparency and democratize his rule as a condition of further aid. Increasingly under criticism, he was eventually compelled to hold a referendum, followed by a democratic presidential election. In 1994 he was defeated, arrested and charged with murder, but acquitted. He died in Johannesburg, South Africa, in 1997 at the age of 98, remembered as the man and doctor who led Malawi to independence but who also instituted one of the most repressive and tyrannical regimes of his era.

Further reading

Kapote Mwakasungura and Douglas Miller. Malawi’s Lost Years (1964-1994): And Her Forsaken Heroes. Mzuni Press, 2016. Philip Short. Banda. Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1974.