Joseph deBettencourt

Chicago, Illinois, United States

Act I: Dr. Daniel Brainard

Beneath the impressive shadow of Notre Dame, a young American cut a path through the winding cobblestone maze of the Île de la Cité to the doors of the Hôtel Dieu, Paris’ oldest hospital. The young man carried with him a diploma from a small medical college in New England, Fairfield Medical College, and his aim was to obtain permission to study under the finest surgeons in the world.1 Daniel Brainard, MD had left his busy surgical practice in the newly incorporated city of Chicago and, after a stop in London, arrived in Paris. After making the necessary introductions, he settled into a routine: rounds and lectures in the morning at Hôtel Charité with Velpeau (author of a popular textbook) and dissections in the afternoon at the École Practique. In between he would fit in rounds as he could at Hôtel Dieu and Hôtel Charité. Over the next two years, he would crisscross from hospital to hospital, the bustling Parisian streets still raw from the Napoleonic revolution, attending lectures, following rounds, and observing dissections performed by his idols. In the evenings, he would have had the chance to experience the city. Only a short walk from the hospitals he could enjoy new productions by Victor Hugo and Alexander Dumas at the newly erected Théâtre de la Renaissance.1,2

This new cosmopolitan lifestyle was unlike anything Brainard had experienced before. At his medical school outside Albany, New York, the class term was scheduled to begin after the fall harvest and end before the spring planting season so that students could get home to their family farms. Chicago had not been much different. The new city was still centered around Fort Dearborn and nestled somewhat contentiously within a large Native American community.3, I Sitting at a café for breakfast, Brainard would have thought about his practice and the community he had come to serve. His time in Paris inspired him to bring home a small part of his Paris experience.

Back in Chicago, Dr. Brainard had already laid the groundwork for his vision. Before his trip he had sought out Dr. Josiah Goodhue,II already well established as a civic leader. Dr. Goodhue had pushed for the creation of Chicago’s first public school system and as the son of a medical school president was a steadfast believer in good education in the city. To that end, the two had drawn up a charter and presented it to the Illinois legislature. The still unnamed school received its charter in 1837 (just before Chicago was incorporated) but because of financial trouble in the city the opening was to be delayed. It was during this interim that Brainard had left for Paris. While he had long held the idea of starting a medical school in Chicago, his trip to Paris had shown him the possibilities and benefits of making this a reality. Now back in Chicago he was determined to start his school, fearing that he would lose out to other schools that were appearing in the area. He had a charter, a board of directors, and some limited funds, but still needed educators for his school.

In 1842 Brainard was invited to teach at the St. Louis University Medical School. There he met James Van Zandt Blaney, an inventive young physician and chemist. Dr. Blaney would later become known for using his skill in chemistry to convict a murderer by detecting the strychnine used to poison his wife.4 For now though, he was a young twenty-two-year-old looking for opportunity. Brainard was impressed by his teaching and invited him to become the first professor at Rush Medical College. While Brainard had been busy teaching and organizing funds for his medical school, competition began to spring up in Illinois and Indiana. Brainard was afraid that if he did not act fast he would not be able to attract students to his new school. “I think it urgent there should be a commencement made this season […] By commencing at present a number of students might be prevented from going from this region to other places and thus give advantages to other schools,”1 Brainard wrote in a letter to John McLean, convincing him to join the faculty at Rush. McLean had been in medical school with Brainard and agreed to come join the faculty along with Moses Knapp, an obstetrician.

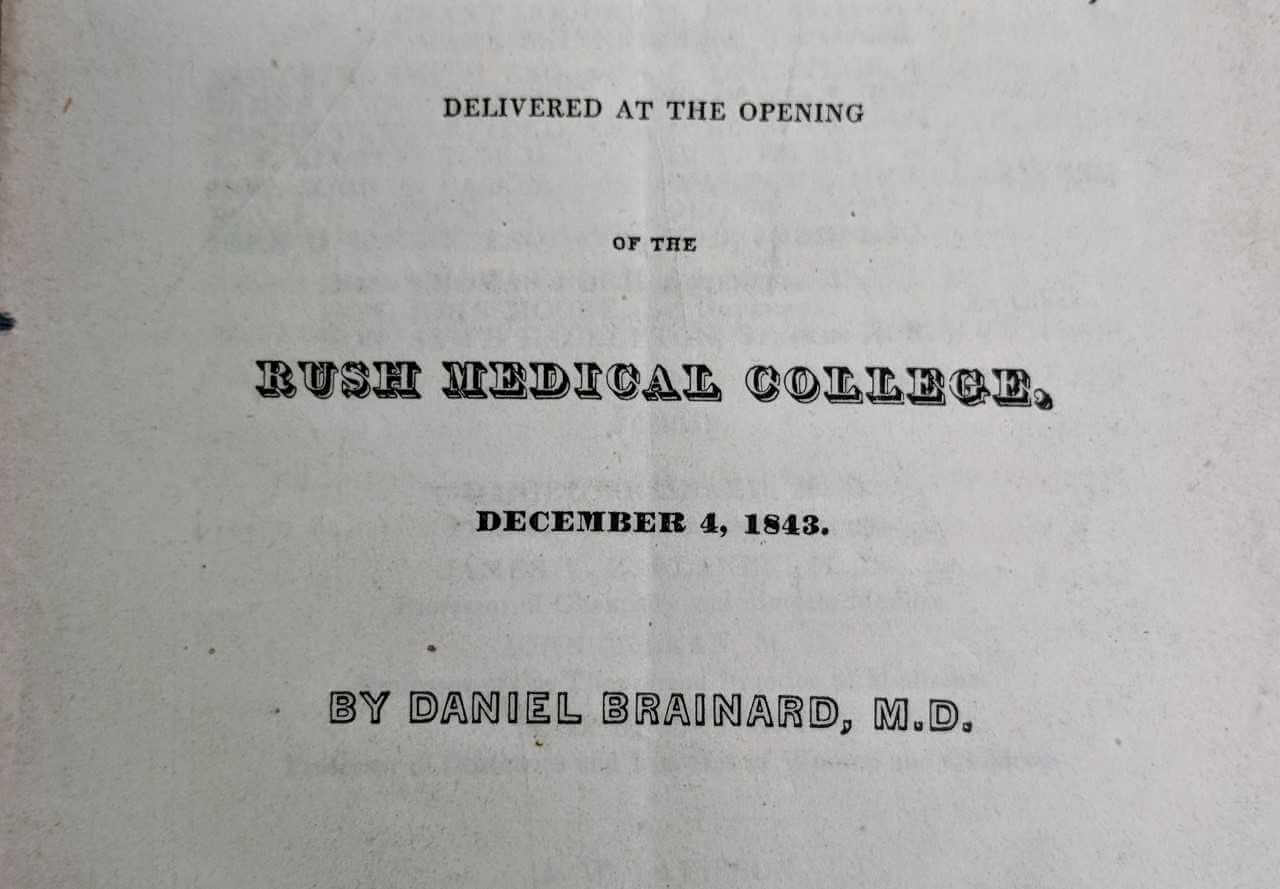

With Brainard teaching anatomy and these three additional teachers, there were now enough physicians to conduct the school’s first sixteen-week session, with classes to begin December 4th, 1843. As Brainard set down to write up an advertisement for his school, he realized a key piece was missing: the name. Not wanting anything to go to waste, he decided to try a gamble. He would name the school “Rush Medical College” after Benjamin Rush, a signer of the Declaration of Independence and father of modern psychiatry. Besides the great respect that the Rush name engendered, Brainard also hoped the naming would inspire the Rush family to make a generous donation to his newly formed school. Brainard needed the cash mainly to secure facilities for the school. While abroad, he had seen the latest in medical technology and hoped to recreate the classrooms and laboratories of Paris in his new medical school. A donation from an eminent medical family could make that possible. Shortly after the announcement went out, Brainard received the anticipated letter from Benjamin Rush’s widow and her two sons. To his dismay, the letter was a thank you note and did not come with the infusion of cash he had hoped for. With little cash and a tight schedule, Brainard’s goal of a purpose-built facility with the latest medical technology would have to wait.

Undeterred from starting classes that year, Brainard set off through the young streets of Chicago to look for a suitable location. He came upon a long wooden building at the corner of Lake and Clark surrounded by shops and factories. The Saloon Building was the largest rental hall in the city; the streets in front of the hall were constantly filled with the swampy mud that Chicago was built upon. Conditions in this area were so poor that the city later raised the entire region up one story to pull it out of the mud and reduce the constant bouts of cholera that tore through the city.5 For now, this location would have to do. As for the anatomy lectures, Brainard created a makeshift space at the back of his office to accommodate a dissection table and a few benches for the students. This first year would be less than glamorous for the students and faculty. Lectures would take place in the barebones rental hall with a schedule fitted around the other rentals for arts shows, religious events, and political rallies.6 The twenty-two students would then be crammed into a small wooden shack for anatomy demonstrations.7 This was not the metropolitan image Brainard had seen in Paris, but it was the beginning of something important for Chicago. For Brainard, medicine was more than a field of study; it was deeply personal. “The health, the happiness, and the life of your dearest friends, and your own, may, and will, some day [sic], depend on the skill of some member of the medical profession,”8 he stated to the students seated in the cold rental hall the first December day of classes. He opened lectures, as was customary, with a speech about this school, at this time, in this city. He held up medicine as a way to better not only the city but also individuals, allowing the children of farmers and merchants to improve their fortunes and those of their children. Medicine, for Brainard, was a way forward. He ended his inaugural lecture that morning with a prediction:

“In conclusion, might we speak of our hopes for the future?–Uncertain as hopes proverbially are, we feel justified in believing that the school we this day open, is destined henceforth to be ranked among the permanent institutions of our State. It must succeed. It may pass, and will in time, into other and abler hands; it may meet with obstacles, be surrounded by difficulties, but it will live on, identified with the interests of a great and prosperous city.” – Daniel Brainard, MD8

Act II: Dr. James Campbell

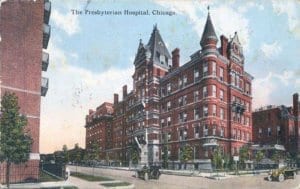

In the 1960’s things would have seemed very normal at Rush Medical College: students sat in lectures, Rush faculty conducted rounds, and the anatomy lab was filled with the familiar odor of formaldehyde. Despite appearances, Rush Medical College had been closed for nearly twenty years. The students studying in the halls were from the neighboring University of Illinois, and while the physicians still carried the title of “Rush Faculty,” they taught classes for University of Illinois students, a relationship that was growing thin.7,9 The closing of Rush Medical School had been the culmination of a simmering tension with the University of Chicago. In the early 1900’s, Rush had sought the support of a larger institution and the University of Chicago in turn was looking to add medicine to their curriculum. The agreement was mutually beneficial for many years and developed into a program where students completed their preclinical years on the southside at the University of Chicago before attending clinical rotations at Rush Medical College on the westside. The ambitious University of Chicago, however, wanted to push their reputation further and looked to east coast schools like Johns Hopkins University for inspiration. Wanting to develop into a research-based institution, the University of Chicago began to bring more research physicians to their staff and moved more of the basic science and didactic training to their southside campus. The Rush faculty were skeptical of these “full-time professors” who did not see patients, and felt there was no way they could teach medicine as well as actively work as physicians.7 As the University of Chicago built and developed their own southside hospital, they began to pressure Rush to move away from the Presbyterian Hospital and formally join the University. Presbyterian Hospital was unmoved by the discussion and firmly stated that their mission was to care for Chicago’s westside community, and that is where they would stay. Besides, Rush physicians did not want to leave their busy practices to work for a University that, as they saw it, was more concerned with research than with patient care. In 1942, Rush and the University of Chicago parted ways and Rush Medical College closed its doors, which had been open since 1843.9, III

This change was not only difficult for the faculty and staff of Rush, but also for the students who applied to study at the University of Chicago. Many students chose the University of Chicago for the opportunity to spend their third and fourth years of study on the floors of Presbyterian Hospital learning from the Rush faculty. Rush, with its long history in Chicago, had cultivated an image of a school focused on patient care and excellence in clinical practice.7 One student affected by this change was James Campbell. A graduate of Knox College, known for his love of the theater and relentless work ethic, he had been accepted to the University of Chicago and began classes in September of 1939 with the intent of spending his clinical years at Rush. That following year, in 1940, the announcement was made that Rush and University of Chicago would part ways; after the current students finished their rotations, no more would be added to Rush.7 At the time this was a big disappointment to James but he found a way to make the best of his situation. After becoming heavily involved in research and pushing through the difficult classes, he managed to obtain a spot at Harvard University for his clinical years. He was an unusual Harvard student, having come from humble beginnings in rural Illinois, but his outgoing personality allowed him to find a place there. He was liked well enough to secure a competitive internship at the Boston City Hospital and managed to continue pursuing research despite a heavy patient load.9 By 1954, he found himself back in Chicago, this time as chairman of the Department of Internal Medicine at Presbyterian Hospital.

Dr. Campbell saw the Rush faculty at Presbyterian and the dormant Rush Medical College charter as an opportunity. The population boom in the years after the war had led to a shortage of physicians in the US. In response, Campbell had embarked on a two-year study entitled Education in the Health Fields for the State of Illinois; the resultant report had made it clear that Illinois needed more physicians. The report found that Illinois currently ranked eighteenth among the states in its ratio of physicians to population. Despite training a large number of physicians, Illinois lost most of them to other states after they graduated. If Illinois were to keep up with demand it would need to enroll more medical students. Many schools also wanted to do so but lacked funding. The state legislature found the report compelling and enacted legislation to help. The government would subsidize capital and one-time costs for the expansion and planning of existing school facilities. They also would provide ongoing direct support to schools based on their class size.10 The first part of this legislation was the key for Campbell and the board of trustees at Rush Medical College. The new legislation provided subsidies to expand existing medical schools. This included Rush, which had maintained its charter for thirty years, waiting for just such an opportunity.

The board of trustees had a number of options. The most convenient would have been the offer from the University of Illinois to reopen Rush Medical College as a new site: The Rush Medical College of the University of Illinois. But the board and the alumni of Rush had long memories. They remembered recent issues with the University of Illinois and the larger struggle during their partnership with the University of Chicago. The board, with their strong ally and author of the so-called “Campbell Report,” hatched a different plan. Rush would merge with their hospital partner, Presbyterian-St. Luke’s and would sign the Rush Medical School charter over to the hospital. The merger would create Rush-Presbyterian-St. Luke’sIV and was made under the agreement that the medical school would reopen within five years; James Campbell would serve as president of this new organization. The Campbell report had emboldened the board of trustees to reform and reinvent their long dormant school. In 1970 Presbyterian-St. Luke’s formally broke ties with the University of Illinois. Campbell, known in college for his theatrical skill, now whipped up excitement, drawing in people from various fields and departments like a ringmaster. The fast pace and whirlwind of activity was not just for show; Campbell had set the ambitious goal of bringing the first new class to Rush in 1971. Like Brainard in 1843, he was determined to bring Rush onto the scene quickly to capitalize on the new legislation. “We are closing the loop between delivering quality health care and producing the manpower to do the job,” Campbell wrote in the 1971-72 Annual report.11 Campbell wanted Rush to stand out in the field and decided that for their inaugural class they would try something unique for the time. The newly formed Rush University for the Health Sciences would expand their admissions criteria, allowing students to apply who had excelled in non-science majors as undergraduates, and began actively seeking out another unique group: women. In 1971, 14% of the inaugural class were women and by the 1980’s 35% of the class would be women.7, V Other things would be very familiar to Rush Medical School. Just like in 1843, Rush Medical College began classes in 1971 in borrowed and repurposed classroom space as the new academic facility was still awaiting construction. There was one more familiar aspect to the start of the 1971 academic year. “We here are revolutionary even in our setting of traditions,” Dr. Campbell began at the inaugural Rush Medical College Luncheon. “You do not, however, escape the speech.”13

This would not be the last time the students would hear Dr. Campbell’s “Five Smooth Stones” speech, for he was fond of giving it. The speech was a reference to the five smooth stones which the biblical David chose to fight Goliath. In the speech he likened the five smooth stones to five objectives of medical education. To him the key point of the story was that David had taken five stones but only used one.

“Remember David hit Goliath with the first stone he threw. We don’t have any real idea what the outcome of this particular battle would have been if he had missed, or had to use a second stone, but I can make a fairly good guess. What we are told, however, seems to me to have a direct application to anyone in medicine. We rarely get second chances, and certainly in those unusual circumstances in which we do, our opportunity for success is almost always less than our initial try.” – James Campbell, MD13

Campbell reasoned that a physician needed to know each one of those five objectives, so that when the chance came he could use any one of them and hit with the first shot. It may also be true that the same could be said for medical schools. This time around there would be less room for error. Medical schools had changed vastly from the first founding of Rush Medical College, as had medical knowledge. Campbell’s school would need to reinvent itself from the Rush that Brainard had begun and be prepared to enter a rapidly developing field with ever-expanding horizons. On that fall day, the future of Rush University was far from certain, but as Dr. Campbell had suggested in his first speech to the class of 1974-5,VI and as Dr. Brainard had suggested to the class of 1845, they were establishing a new tradition, one that continues to this day.

Image credits

- Figure 1. “A Lecture Introductory to the Course of Anatomy and Surgery, Delivered at the Opening of the Rush Medical College, December 4, 1843,” by Daniel Brainard, MD. From the Daniel Brainard Papers, #651, Courtesy of the Rush University Medical Center Archives, Chicago, Ill.

- Figure 2. “The Parisian surgeon and anatomist A. Velpeau (1795-1867) performing an anatomical dissection.” Etching, after a painting by F. N. A. Feyen-Perrin, 1864. Wellcome Collection, https://wellcomecollection.org/works/cnmzvbxb licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0)

- Figure 3. “Postcard of Presbyterian Hospital and Rush Medical College, corner of Wood and Congress Streets, 1917.” From the Postcard Collection, Courtesy of the Rush University Medical Center Archives, Chicago, Ill.

Endnotes

- I. Fort Dearborn was destroyed by the Potawatomi during the war of 1812, and the fort was rebuilt again in 1816.

- II. Despite his apparent philanthropic goals, the most commonly repeated fact about Dr. Goodhue is that he died one night by falling into an open manhole on his way to see a patient.

- III. The announcement was made in 1939 that the University of Chicago would only be accepting new students to their campus. The students already destined to do their clinical years at Rush would complete them and then the program would end.

- IV. In 2003 Rush-Presbyterian-St. Luke’s Medical Center was renamed Rush University Medical Center, which is more concise and, in my opinion, makes an easier acronym.

- V. These numbers are slightly ahead of or at pace with national rates at the time. By 1980 many schools had similar percentages but in the early 1970s many schools were not as accepting or as active in recruiting.12

- VI. In 1971 Rush Medical College offered both a 3-year and 4-year option for medical school students, but ended up getting rid of the 3-year accelerated program because they found that students where no better trained and much more exhausted than their 4-year compatriots.

References

- Kinney J. Saga of a Surgeon: The Life of Daniel Brainard, M.D. Springfield, Ill: Southern Illinois University School of Medicine; 1987.

- Le théâtre de la Renaissance à Paris – Photos et historique. Théâtre Renaiss. https://theatredelarenaissance.com/le-theatre/. Accessed June 14, 2018.

- Quaife MM. Chicago and the Old Northwest, 1673-1835: A Study of the Evolution of the Northwestern Frontier, Together with a History of Fort Dearborn. University of Illinois Press; 2001.

- Kelly HA (Howard A, Burrage WL (Walter L. American Medical Biographies. Baltimore, The Norman, Remington Company; 1920. http://archive.org/details/americanmedica00kell. Accessed July 13, 2018.

- Young D. Raising the Chicago streets out of the mud. chicagotribune.com. http://www.chicagotribune.com/news/nationworld/politics/chi-chicagodays-raisingstreets-story-story.html. Accessed July 13, 2018.

- Saloon Building. http://www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/3513.html. Accessed July 13, 2018.

- Bowman J. Good Medicine: The First 150 Years of Rush-Presbyterian-St. Luke’s Medical Center. Chicago Review Press; 1987. http://archive.org/details/goodmedicinefirs00bowm. Accessed May 23, 2018.

- Brainard D. Lecture Introductory to the Course of Anatomy & Surgery. Presented at the: December 4, 1843; Rush Medical College.

- Flanagan MJ. To the Glory of God and the Service of Man: The Life of James A. Campbell, M.D. Winnetka, Ill: FHC Press; 2005.

- 110 ILCS 215/ Health Services Education Grants Act. http://www.ilga.gov/legislation/ilcs/ilcs3.asp?ActID=1082&ChapterID=18. Accessed July 30, 2018.

- Rush-Presbyterian-St. Luke’s Medical Center (Chicago I). Annual Report, 1971-1972. [Chicago, Illinois] : Rush-Presbyterian-St. Luke’s Medical Center.; 1971. http://archive.org/details/annualreport19711971rush. Accessed July 18, 2018.

- Jolly P. Medical Education In The United States, 1960–1987. Health Aff (Millwood). 1988;7(suppl 2):144-157. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.7.2.144

- Campbell J. Five Smooth Stones. Presented at the: 1971; Rush Medical College Luncheon.

JOSEPH deBETTENCOURT is a medical student at Rush Medical College in Chicago, Illinois, with an interest in pediatrics. He attended Northwestern University where he received a BA in Theatre and Pre-Medical Studies. He has worked as a professional actor, designer, and carpenter, as well as a standardized patient, and medical researcher.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 11, Issue 2 – Spring 2019

Leave a Reply