Wilson F. Engel, III

Gilbert, Arizona, United States

|

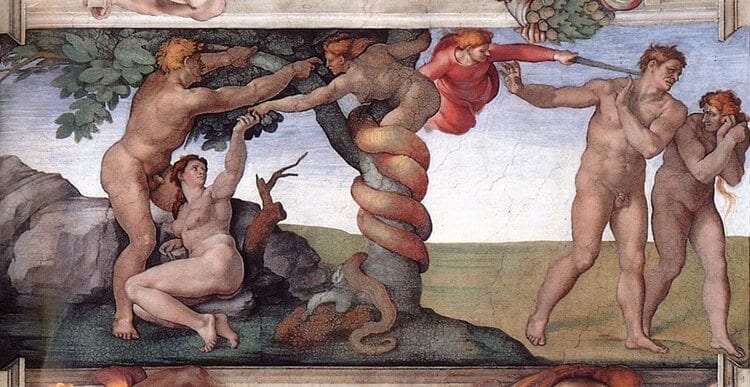

| Figure 1. The Fall and Expulsion of Adam and Eve, 1510 AD. Michelangelo, Fresco, Sistine Chapel, Vatican, Rome. |

Michelangelo’s famous fresco in the Sistine Chapel (Figure 1) shows the serpent tempting Eve on the left, and the archangel Raphael expelling Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden on the right. The image oddly enough shows the serpent having a female face, its massive body doubled over on itself, strangling the tree.

|

|

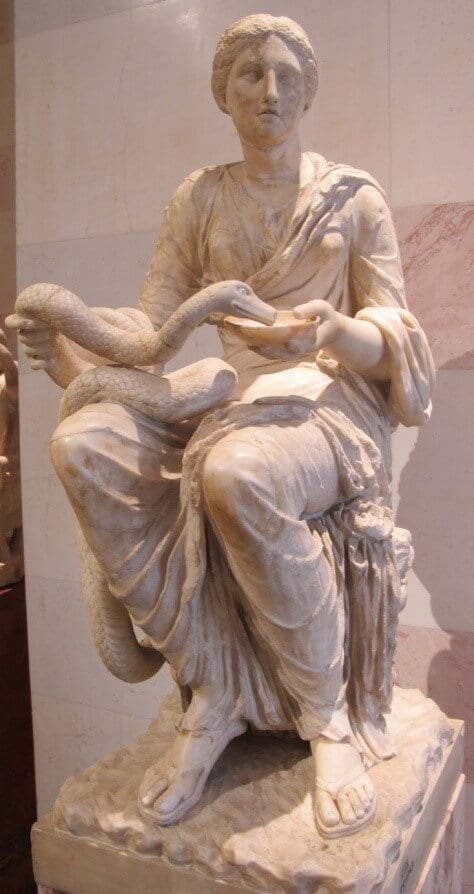

| Figure 2. Asclepius Standing with His Staff and Serpent | Figure 3. Hygeia Seated on Olympus with Her Sacred Serpent and Bowl |

The Classical Greek and Roman image of a snake wrapped around an erect wooden object was also the traditional symbol for Asclepius, the Classical god of medicine (Figure 2). Yet more interesting was the linkage of a snake to Asclepius’ daughter Hygeia, goddess of health, sanitation, and diet. Her standing or seated sculptures identify her by the huge snake crossing her right arm to feed at the shallow bowl she holds in her left hand. (Figure 3) Her bowl became the emblem of pharmacology while her snake became the emblem of resurrection, facilitated by its feasting on the contents of the bowl.

Archaeology has uncovered representations of Asclepius and Hygeia throughout the Eastern Mediterranean and Asia Minor. The god is often shown next to a tree or staff with the serpent wrapping and undulating itself up the wood. The goddess, often linked to a chthonic female deity, held a serpent in each raised hand as if the reptiles were scepters or symbols invoking her powers. (Figure 4) Some statues of Hygeia show her standing with both arms raised without snakes in her hands, or holding her liquid drapery aloft while she steps forward boldly.

|

|

| Figure 5. Michelangelo,“System of Frescos in the Sistine Chapel Ceiling,” 1508-1512. |

The symbolism of the wooden post or Tree of Life, or Death, may be interpolated as the cross of Jesus in the Christian tradition. The apple, plucked from the Tree, was the fatal and God-forbidden fruit. While the tree in Michelangelo’s fresco portends the death of Adam and Eve, it also looks toward mankind’s future redemption through the wood of the cross. If the viewer stands back from the medley of frescos, the wholeness and consistency of the divine order is evident. (Figure 5)

Art historical descendants of images of Hygeia include famous works by Peter Paul Rubens and Gustav Klimt (the latter probably lost during the Nazi depredations of the last century). The Rubens painting makes several interesting innovations on tradition. (Figure 6) Rubens’ Hygeia force-feeds the serpent (held on her left, not her right arm) from a glass vial filled with a liquid that appears similar to blood —it is the same blood-red color as Hygeia’s robe. The implied reference to Christian Communion—the feast designed to make the participant hale and whole in Christ—is unmistakable.

The University of Vienna Ceiling Paintings by Klimt include his Hygeia, 1900-1907. (Figure 7) Explicitly related to Philosophy, Medicine, and Jurisprudence, these paintings came under attack in their own time for “pornography” and “perversion.” They are thought to have been destroyed by retreating Nazi SS forces, though this has not been verified. The image of Hygeia is a detail from the Medicine painting, which showed graphic representations of contemporary medicine, including suffering and death. The goddess has turned her back on humankind. Her Aesculapian snake has become a jaundiced ribbon crossing over her right side to her left while the cup “of Lethe” remains in her left, tantalizingly below the snake’s head.

With a heritage extending back through the entire Western tradition, Hygeia became a powerful Christian figure for the Vatican, connecting formerly pagan rites to the most holy Christian feast of Communion. The Classical goddess’ place in the context of secular medicine was transformed into a role in a sacrament instilling sacred Christian harmony, thus paving the way not to Classical Lethean forgetfulness but to an awakening to individual salvation.

|

|

|

| Figure 4. Minoan Snake Goddess Figurine, 1600 BCE | Figure 6. Peter Paul Rubens, Oil Painting, Hygeia-Goddess of Health, 1615. | Figure 7. Gustav Klimt “Hygeia” (Detail from Medicine, University of Vienna), 1900-1907. |

WILSON F. ENGEL, III, PhD, is a Shakespeare scholar and long-time student of the influences of the Classics on Christian life and thought in the late Middle Ages and Renaissance. He was founder and editor of the scholarly newsletter Renaissance and Renascences in Western Literature.

Leave a Reply