Sarah Riedlinger

Dean Giustini

Brenden Hursh

Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada

Progress in diabetes care between 1922 and 1929

In 1923 Banting joined the staff of the Hospital for Sick Children and was placed in charge of diabetes care. He and physician Gladys Boyd developed a comprehensive program of treating children with diabetes. The program resulted in a 50% decrease in childhood diabetes-related mortality over a ten-year period.1 Between 1922 and 1929 their clinical work provided new insights into diabetes as a disease entity and the reason insulin was an effective treatment.

Banting and Boyd’s findings are documented in several articles between 1922 and 1929. Their work highlighted the importance of urine testing in children presenting with polyuria.2 As early as 1923 Boyd emphasized that death from diabetic coma due to missed diagnosis was “unnecessary.”3

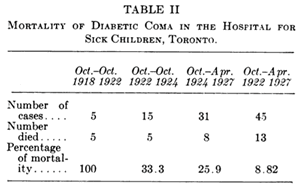

In 1927 Boyd published a paper highlighting the change in life expectancy for patients only four years after insulin’s discovery.4 Before insulin, children with diabetes were kept alive by undernutrition, often to the point of starvation, so that many “might better be said to have existed rather than lived.”5 Figure 2 shows a marked decrease in mortality for children presenting in diabetic coma. Boyd attributed her results to insulin therapy, prompt admission to hospital, and recognition of disease.6

Pediatric patients’ perspectives: Ryder, Needham, and Hughes

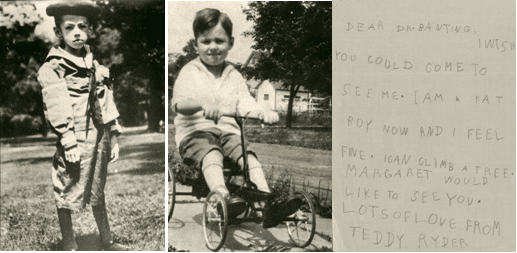

It is said a picture is worth a thousand words. Such is the case of Teddy Ryder, a six-year-old boy and one of Banting’s memorable patients. Before treatment, Ryder weighed a frail twenty-seven pounds. Owing to insulin he lived a long life and died at the age of seventy-seven in the US. His thank-you letter to Banting is memorable, and his photos show the impact insulin therapy had on his vitality (Figure 3).

Eleven-year-old Elsie Needham was the first of Banting’s patients to recover from diabetic coma. Banting’s attempts to save her are described in “The Story of Insulin” as he worked around the clock to monitor her symptoms and evaluate her response to treatment. Banting said, “I lived at the hospital day and night for three days and was there every few hours for a week.”10 He was treating an illness never successfully treated before and had only his intuition as a clinician to rely on. The story of her remarkable recovery was published in the newspapers in October 1922:

[Needham’s] condition was pronounced hopeless by a number of medical men who examined her. . . . The child was unconscious several days, and little hope was held for recovery. While the disease had reached an advanced stage, the child has responded to the treatment wonderfully well. Her condition continues to show signs of improvement each succeeding day.11

Elizabeth Hughes was the fifteen-year-old daughter of the US Secretary of State, Charles Hughes, and one of Banting’s most publicized patients. She was diagnosed with diabetes in 1919 and had survived through strict caloric restriction. She received her first insulin injection on 17 August 1922 and returned home to Washington 30 November 1922. Given the notoriety of this family, her cure was advertised in the Toronto newspapers as early as 16 October 1922:

. . . Miss Elizabeth Hughes . . . has been taking Insulin treatment for diabetes for about two months under the personal attention of Dr. F. Banting, discoverer of the treatment. She has gained 16 pounds and is eating everything . . . When she came here she was suffering from the malady in acute form. As is customary with patients of this type, she was unable to assimilate the staple foods which contain carbohydrates . . . and so was forced to adopt a diet so severely restricted it was almost at starvation point.12

In her letters, Elizabeth told her mother that she found her newfound energy “thrilling,” and that being able to lead a “normal, healthy existence is beyond all comprehension.”13 Banting’s patients came to him malnourished and deprived of the necessary nutrients to survive. In the 1920s, weight gain in diabetes was associated with a return to health. Hughes’ story represents a departure from starvation as the only way to keep children alive and attests to the turnabout in therapy. Hughes would eventually become a notable figure in civic affairs, best known for founding the Supreme Court Historical Society in 1972, of which she was president until 1979. She lived to be seventy-three years old, passing away in 1981.

Conclusions and reflections on the last 100 years of diabetes care

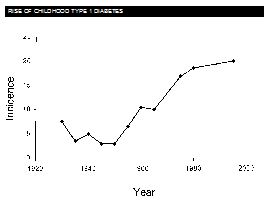

The discovery of purified insulin in 1922 was the beginning of a new era for diabetes, one with considerable promise for pediatric patients around the world. Between 1920 and 1950, diabetes changed from a fatal disease to one where survival was possible. The paper “The Rise of Childhood Type 1 Diabetes in the 20th Century” highlights the impact of insulin therapy on longevity and notes the increasing incidence of this disease over time (Figure 4).14

In the last century, as diabetes has become more prevalent, our understanding of the disease has greatly improved. But as life expectancy has increased, chronic complications have become more common and represent new challenges. We now realize that the complications of diabetes are due to poor glycemic control. In 1993 the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial demonstrated the relationship between the degree of glycemic control and complications of diabetes (nephropathy, neuropathy, retinopathy, and cardiovascular disease).15

Diabetes is now viewed as a treatable condition. Its high prevalence has motivated pharmaceutical companies to create new ways to improve glycemic management.16, 17 Banting’s patients received insulin purified from animal extract, but by the 1930s Hagedorn in Denmark had developed a way to conjugate insulin to proteins to prolong its duration of action.18 Patients of the twenty-first-century use engineered insulin analogs.19 Home monitoring equipment and blood and urine testing for glucose and ketones are readily available and have resulted in better glycemic management.20 Patients no longer need to use syringes for insulin administration; pens and continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion pumps are now mainstream.21

We continue to face new challenges in the fight against diabetes. While physicians better understand its pathophysiology and have effective methods for treatment, the rates of diabetes are increasing on a global scale among children and adolescents. On the horizon are new treatments and ongoing hope for a permanent cure. Today’s diabetes professionals can find inspiration in the example of Banting and Best and the impact of insulin, not just for children treated at the Toronto Hospital for Sick Children from 1922 to 1929, but for all children now and in the future.

End notes

- Hospital for Sick Children (SickKids), Toronto. “About SickKids. Timeline: 1901-1925.” Accessed 15 February 2018. http://www.sickkids.ca/AboutSickKids/History-and-Milestones/Milestones/1901-1925/index.html.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Gladys L Boyd, “Course and Prognosis of Diabetes Mellitus in Children,” Canadian Medical Association Journal, 17 (1927): 1167-72.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- University of Toronto, Fisher Library Digital Collections, “Photograph of Teddy Ryder, 10/07/1922. Original Photograph Showing Teddy Ryder when He First Arrived in Toronto Weighing 27 Pounds.” Accessed 2 Mar 2018. https://insulin.library.utoronto.ca/islandora/object/insulin%3AP10037#page/1/mode/1up/search/teddy%20ryder

- University of Toronto, Fisher Library Digital Collections, “Letter to Dr. Banting Ca. 1923, Ryder, Teddy (Theodore). MS. COLL. 76 (Banting), Box 8B, Folder 11. ” Accessed 2 Mar 2018. https://insulin.library.utoronto.ca/islandora/object/insulin%3AP10037#page/1/mode/1up/search/teddy%20ryder.

- University of Toronto, Fisher Library Digital Collections, F. G. Banting (Frederick Grant, Sir) Papers. Banting Scrapbooks, Scrapbook 1, pp. 34, 35. Accessed 15 Feb 2018. https://resource.library.utoronto.ca/insulin/scrapbooks.cfm

- University of Toronto, Fisher Library Digital Collections, F. G. Banting (Frederick Grant, Sir) Papers. “Insulin method saves Galt girl”. [October 1922]. MS. COLL 76 (Banting) Scrapbook 1, Box 1, Page 88. Accessed 2 Mar 2018.

- https://insulin.library.utoronto.ca/islandora/object/insulin%3AC10113#page/1/mode/1up/search/elsie%20needham

- University of Toronto, Fisher Library Digital Collections, F. G. Banting (Frederick Grant, Sir) Papers. “Insulin method saves Galt girl”. [October 1922]. MS. COLL 76 (Banting) Scrapbook 1, Box 1, Page 88 Accessed 2 Mar 2018.

- https://insulin.library.utoronto.ca/islandora/object/insulin%3AC10113#page/1/mode/1up/search/elsie%20needham

- University of Toronto, Fisher Library Digital Collections, F. G. Banting (Frederick Grant, Sir) Papers. Letter to mother 22/08/1922. Hughes, Elizabeth Evans. Original not in Fisher Collection MS. COLL 334 (Hughes) Box 1, Folder 35A. Accessed 2 Mar 2018. https://insulin.library.utoronto.ca/islandora/object/insulin%3AL10006#page/1/mode/1up/search/elizabeth%20hughes

- Edwin A. M. Gale, “The Rise of Childhood Type 1 Diabetes in the 20th Century,” Diabetes, 51, no. 5 (2002): 3353-3361.

- Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT), “The Effect of Intensive Treatment of Diabetes on the Development and Progression of Long-Term Complications in Insulin Dependent Diabetes Mellitus,” New England Journal of Medicine, 329, no. 14 (1993): 977-86.

- Gale, 2002.

- J. C. Pickup, “Banting Memorial Lecture 2014 Technology and Diabetes Care: appropriate and Personalized,” Diabetic Medicine, 32, no. 1 (2015): 3-13.

- Bliss, 1993.

- Celeste C. Quianzon, and Issam Cheikh. “History of Insulin,” Journal of community and Hospital Internal Medicine Perspectives, 2, no. 2 (2012): 1-3.

- J. D. Baum, “Home Monitoring of Diabetic Control,” Archives of Disease in Childhood, 56, no. 12 (1981): 897-899.

- Andrew Fry, “Insulin Delivery Device Technology 2012: where are we after 90 Years?”, Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology, 6, no. 4 (2012): 947-53.

References

- Allan, Frank N. “Diabetes before and after insulin.” Medical History 16, no. 3 (1972): 266-273.

- Diabetes Canada. Accessed 15 Feb 2018 http://www.diabetes.ca/about-diabetes/history-of-diabetes.

- Diapedia. Accessed 15 Feb 2018 https://www.diapedia.org/type-1-diabetes-mellitus/2104085152/discovery-of-type-1-diabetes.

- Banting, Frederick. “Further Clinical Experience with Insulin (Pancreatic Extracts) in the Treatment of Diabetes Mellitus.” British Medical Journal 1, no. 3236 (1923): 8-12.

- Banting, Frederick, Charles H. Best, JB Collip, WR Campbell, AA Fletcher. “Pancreatic Extracts in the Treatment of X Diabetes Mellitus.” Canadian Medical Association Journal 12, no. 3 (1922): 141-146.

- Baum, J. D. “Home Monitoring of Diabetic Control.” Archives of Disease in Childhood 56, no. 12 (1981): 897-899.

- Barron, Moses. The relation of the islets of Langerhans to diabetes with special reference to cases of pancreatic lithiasis. Franklin H. Martin Memorial Foundation, 1920.

- Bliss, Michael. “The History of Insulin.” Diabetes Care 16 (1993): 495-503.

- Bliss, Michael. The Discovery of Insulin. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1982.

- Boyd, Gladys L. “The Treatment of Diabetes in Children.” Canadian Medical Association Journal 42, no. 5 (1940): 438-442.

- Boyd, Gladys L. “The Treatment of Diabetic Coma in Children.” Canadian Medical Association Journal 21, no. 5 (1929): 520-523.

- Boyd, Gladys L. “Course and Prognosis of Diabetes Mellitus in Children.” Canadian Medical Association Journal 17 (1927): 1167-72.

- Boyd, Gladys L. “Insulin Treatment in Diabetes in Children.” Canadian Medical Association Journal 14, no. 1 (1923): 33-40.

- Canadian Diabetes Association. Diabetes: Canada at the Tipping Point – Charting a New Path, [2011]. Accessed 15 Feb 2018 https://www.diabetes.ca/CDA/media/documents/publications-and-newsletters/advocacy-reports/canada-at-the-tipping-point-english.pdf.

- Canadian Press. “May Cure Diabetes.” Toronto Star., 10 January 1922.

- Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT). “The Effect of Intensive Treatment of Diabetes on the Development and Progression of Long-Term Complications in Insulin Dependent Diabetes Mellitus.” New England Journal of Medicine 329, no. 14 (1993): 977-86.

- Fry, Andrew. “Insulin Delivery Device Technology 2012: Where are we After 90 Years?” Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology 6, no. 4 (2012): 947-53.

- Gale, Edwin A. M. “Historical Aspects of Type 1 Diabetes.” Diapedia: The Living Textbook of Diabetes. August, no. 13 (2014): https://www.diapedia.org/type-1-diabetes-mellitus/2104085134/historical-aspects-of-type-1-diabetes-https://www.diapedia.org/type-1-diabetes-mellitus/2104085134/historical-aspects-of-type-1-diabetes.

- Gale, Edwin A. M. “The Rise of Childhood Type 1 Diabetes in the 20th Century.” Diabetes 51, no. 5 (2002): 3353-3361.

- Gemmill, Chalmers L. “The Greek Concept of Diabetes.” Bulletin of the New York Academic of Medicine 48, no. 8 (1972): 1033-36.

- Gillespie, Kathleen M. “Type 1 Diabetes: Pathogenesis and Prevention.” Canadian Medical Association Journal 175, no. 2 (2010): 165-170.

- Himsworth, H. P. “Diabetes Mellitus: Its Differentiation into Insulin-Sensitive and Insulin-Insensitive Types. 1936.” International Journal of Epidemiology 42, no. 6 (2013): 1594-1598.

- Joslin, E. P. “The Treatment of Diabetes Mellitus.” Canadian Medical Association Journal 14, no. 9 (Sep 1924): 808-811.

- Joslin, E. P. “The Treatment of Diabetes Mellitus.” Canadian Medical Association Journal 6, no. 8 (Aug 1916): 673-684.

- Lindsay, Lionel M. “Diabetes Mellitus in a Child of Three.” Canadian Medical Association Journal 7, no. 2 (1917): 133-5.

- Mazur, Allan. “Why were “Starvation Diets” Promoted for Diabetes in the Pre-Insulin Period?” Nutrition Journal 10, no. 1 (2011): 23-23.

- Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine 1923. Frederick G. Banting, John Macleod. Nobel Lecture, September 15, 1925. Diabetes and Insulin. Accessed 15 Feb 2018. https://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/medicine/laureates/1923/banting-lecture.html

- Pickup, J. C. “Banting Memorial Lecture 2014 Technology and Diabetes Care: Appropriate and Personalized.” Diabetic Medicine 32, no. 1 (2015): 3-13.

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Diabetes in Canada: Facts and Figures from a Public Health Perspective. Ottawa, Ontario.: Government of Canada., 2011.

- Quianzon, Celeste C., and Issam Cheikh. “History of Insulin.” J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2, no. 2 (2012): 1-3.

- Rosenfeld, Louis. “Insulin: Discovery and Controversy.” Clinical Chemistry 48, no. 12 (2002): 2270-2288.

- Roth, Jesse, Sana Qureshi, Ian Whitford, Mladen Vranic, C. Ronald Kahn, I. George Fantus, and John H. Dirks. “Insulin’s discovery: new insights on its ninetieth birthday.” Diabetes/Metabolism Research and Reviews 28, no. 4 (2012): 293-304.

- The Hospital for Sick Children (SickKids). Toronto. “About SickKids. Timeline: 1901-1925.” Accessed 15 Feb 2018. http://www.sickkids.ca/AboutSickKids/History-and-Milestones/Milestones/1901-1925/index.html.

- University of Toronto. Fisher Library Digital Collections. “1920-1925. the Discovery and Early Development of Insulin. ” Accessed 15 Feb 2018https://resource.library.utoronto.ca/insulin/index.html.

- University of Toronto. Fisher Library Digital Collections. “Letter to Dr. Banting Ca. 1923. Ryder, Teddy (Theodore). MS. COLL. 76 (Banting), Box 8B, Folder 11. ” Accessed 15 Feb 2018. https://resource.library.utoronto.ca/insulin/digobject.cfm?idno=L10021&Page=0001&size=1&query=ryder&searchtype=fulltext&searchstrategy=all&startrow=1&media=all&sort=date_asc&photo=on&refine=no&transcript=

off#bibrecord - University of Toronto. Fisher Library Digital Collections. “Patient Records for Leonard Thompson. MS. COLL. 76 (Banting), Box 8B, Folder 17B. Dec 1921 – Jan 1922. ” Accessed 15 Feb 2018. https://resource.library.utoronto.ca/insulin/digobject.cfm?idno=M10015&Page=0001&size=2&query=toronto%20AND%20general%20AND%20hospital&searchtype=fulltext&searchstrategy=all&startrow=1&media

=all&sort=date_asc&photo=on&transcript=off&refine=no. - University of Toronto. Fisher Library Digital Collections. “Photograph of Teddy Ryder, 10/07/1922. Original Photograph Showing Teddy Ryder when He First Arrived in Toronto Weighing 27 Pounds.” Accessed 15 Feb 2018. https://resource.library.utoronto.ca/insulin/digobject.cfm?idno=P10037&Page=0001&size=1&query=ryder&searchtype=fulltext&searchstrategy=all&startrow=1&media=all&sort=date_asc&photo=on&refine=no&transcript=

off#bibrecord - University of Toronto. Fisher Library Digital Collections. F. G. Banting (Frederick Grant, Sir) Papers. Banting Scrapbooks, Scrapbook 1, pp. 34, 35. Accessed 15 Feb 2018.

- University of Toronto. Fisher Library Digital Collections. F. G. Banting (Frederick Grant, Sir) Papers. “Insulin method saves Galt girl”. [October 1922]. MS. COLL 76 (Banting) Scrapbook 1, Box 1, Page 88. Accessed 15 Feb 2018. https://insulin.library.utoronto.ca/digobject.cfm?idno=C10113&Page=0001&size=1&query=Elsie%20AND%20Needham&searchtype=fulltext&searchstrategy=All&startrow=1&media=all&sort=title_sort&photo=

on&transcript=off&refine=no - University of Toronto. Fisher Library Digital Collections. F. G. Banting (Frederick Grant, Sir) Papers. Letter to F. G. Banting 01/01/1923. Hughes, Elizabeth Evans. MS. COLL. 76 (Banting), Box 8A, Folder 26A. Accessed 15 Feb 2018. https://resource.library.utoronto.ca/insulin/digobject.cfm?idno=L10017&Page=0001&size=1&query=elizabeth%20AND%20hughes%20AND%20letter&searchtype=fulltext&searchstrategy=all&startrow=1&media=

all&sort=title_sort&photo=on&transcript=off&refine=no - University of Toronto. Fisher Library Digital Collections. F. G. Banting (Frederick Grant, Sir) Papers. Letter to mother 22/08/1922. Hughes, Elizabeth Evans. Original not in Fisher Collection MS. COLL 334 (Hughes) Box 1, Folder 35A. Accessed 15 Feb 2018. https://insulin.library.utoronto.ca/digobject.cfm?idno=L10006&Page=0001&size=1&query=Ruth%20AND%20Whitehill&searchtype=fulltext&searchstrategy=all&startrow=1&media=all&sort=title_sort&photo=

on&transcript=off&refine=no - University of Toronto. Fisher Library Digital Collections. F. G. Banting (Frederick Grant, Sir) Papers. Letter to Dr. Banting 02/11/26. Hughes, Elizabeth Evans. MS. COLL. 76 (Banting), Box 8A, Folder 26A. Accessed 15 Feb 2018. https://resource.library.utoronto.ca/insulin/digobject.cfm?idno=L10018&Page=0001&size=1&query=elizabeth%20AND%20hughes%20AND%20letter&searchtype=fulltext&searchstrategy=all&startrow=1&media=

all&sort=title_sort&photo=on&transcript=off&refine=no - Vipond, Mary. “A Canadian Hero of the 1920s: Dr. Frederick G. Banting.” Canadian Historical Review 63, no. 4 (1982): 461-486.6.

Acknowledgements

We would like to extend our thanks to the University of Toronto Banting Archives, especially to archivists Jacob Keszei and Jennifer Toews, for assisting us in locating multiple resources and documents from the Fisher Library Digital Collections and the Banting and Best fonds.

SARAH RIEDLINGER, BSc (Hon), MD, is a Pediatric Resident in the Department of Pediatrics at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada.

DEAN GIUSTINI, MLS, MEd, is a Biomedical Branch Librarian at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver Canada.

BRENDEN E. HURSH, MD, MHSc, FRCPC, is a doctor in the Endocrinology & Diabetes Unit at British Columbia Children’s Hospital and the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada.

Leave a Reply