JMS Pearce

Hull, UK

Few would dispute that Lord Byron (Fig 1) was both a poetic prodigy and a flamboyant rogue. George Gordon Noel, sixth Baron Byron (1788–1824), was born on 22 January 1788 at Holles Street, London, son of Captain John (“Mad Jack”) Byron and his second wife, Catherine, née Gordon. John Byron was a libertine, said to have squandered the fortunes of both his wives.

Lord Byron was celebrated in the Romantic period for his wondrous if portentous literary works that included: “Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage,” “Manfred,” “Don Juan,” “The Destruction of Sennacherib,” and short lyrics such as “She Walks in Beauty” and “So, We’ll Go No More A Roving.”1

He was born with a deformity of his leg and foot that plagued him all his life. A plainly autobiographical allegory is seen in his The Deformed Transformed (1824), left unfinished at his death, where the hunchback Arnold has “a cloven hoof” (I.i.104) and is taunted by his mother.

He grew up in a volatile aristocratic world that swung between violence, poverty, and moments of tenderness. What served to aggravate the suffering imposed by his deformity was the inhumane treatment he received, ostensibly to correct the deformity, and the jeering taunts—even from his mother. “A lame brat,” was the most hurtful of the many epithets she hurled at him.2 Byron spent his formative years in a closed, intensely emotional world, dramatized by his mother’s straitened circumstances, and by his pain and tortured self-consciousness arising from his deformed foot. In April 1801 he entered Harrow School, under the headmaster, Dr Joseph Drury, but made tempestuous and erratic progress. He went to Trinity College, Cambridge in 1805–1807 where amongst many outrages, profligacy, and eccentricities he bought a tame bear, which he kept in the tower above his rooms as a protest against college rules that forbade keeping his bulldog Smut in college. In a letter to his sister he appears to have enjoyed Cambridge:

Trin. Coll. (Wednesday), Novr. 6th, 1805

My Dear Augusta, – As might be supposed I like a College Life extremely, especially as I have escaped the Trammels or rather Fetters of my domestic Tyrant Mrs Byron, who continued to plague me during my visit in July and September. I am now most pleasantly situated in Superexcellent Rooms,… I am allowed 500* a year, a Servant and Horse, so Feel as independent as a German Prince who coins his own Cash, or a Cherokee Chief who coins no Cash at all, but enjoys what is more precious, Liberty.1

In 1807 he travelled for two years through Portugal, Spain, Albania, Greece, and Turkey (where he famously swam the Hellespont in May 1810, a distance of about 4 miles). In April 1808, aged twenty, Byron acquired his inheritance, Newstead Abbey, in terrible disrepair, which to alleviate his debts he sold ten years later for £95,00. He had a disastrous marriage to Annabella Milbanke with whom he had a mathematically gifted daughter, Ada Lovelace, who worked with Charles Babbage’s Analytical Engine and initiated the programming language ADA, named in her honor.

He had affairs with Countess Teresa Guiccioli† and Lady Caroline Lamb.2 He was suspected of having fathered Elizabeth Medora Leigh, born 15 April 1814: daughter of his stepsister Augusta Leigh. Medora is the name of one of the heroines in his poem The Corsair. And with Mary Shelley’s stepsister, Claire Clairmont, he had a daughter, Allegra.

Apart from habitual excess of alcohol, Byron suffered intermittently from fluctuating anorexia and obesity, his weight varying varying from 14st 6lb down to 9st 11lb.3 In a visit to Greece in 1810 and later in Italy he almost certainly had malaria, but recovered.

Byron left England in 1816, never to return. He lived for the next seven years in Switzerland and Italy. Subsequently, in Missolonghi, in December 1823 he aided revolutionary forces in a heroic struggle for Greek independence from Ottoman Turkey. There in February 1824 he became ill with fever, headache, and bone pains. After a bout of heavy drinking he had an epileptic fit:

He fell upon the floor, agitated by violent spasmodic movements of all his limbs. He foamed at the mouth, gnashed his teeth, and rolled his eyes like one in an epilepsy. After remaining about remaining about two minutes in this state his senses returned.5 (p. 118)

He recovered but suffered from dizziness and spasms in the chest, and a few days later suffered a second convulsion. He became febrile with periodic rigors and delirium and died on 19 April 1824, aged thirty-six. Differing diagnoses of typhoid, typhus, uremia, malaria, or rheumatic fever were suspected on tenuous evidence.

The autopsy performed by Dr. Bruno was described by Marchand (p. 1233)‡ as “miserably brief’’ and not surprisingly inconclusive. Millingen reported: generalized injection, thickening and adhesions of the cranial dura. The pia mater presented the appearance of the conjunctiva on an inflamed eye,… an acute inflammatory process superimposed upon an old chronic one.4,3,5

His embalmed body was brought to England, but because of his “questionable morality” the clergy refused to bury him at Westminster Abbey. He was buried at St. Mary Magdalene, Hucknall, near Newstead Abbey. In 1969 a memorial to Byron was finally placed at Westminster in Poets’ Corner 145 years after his death. At the entrance to the National Garden in Athens, commemorating their hero is commemorated with a statue of a woman crowning Byron, sculpted by Henri-Michel Chapu and Alexandre Falguière, erected in 1896.

Deformity

Some medical descriptions survive. John Hunter (1728–1793) examined Byron as a child and diagnosed a clubfoot, but wisely predicted, “It will do very well in time.” In July 1799, Dr Matthew Baillie (1761–1823) examined the eleven-year-old Byron’s “club foot”; (p. 15) at his recommendations Mr. T. Sheldrake made a brace.6,10,7 Although he often wore specially made shoes to hide the deformed foot, Byron refused to wear any type of brace.

Edward Trelawny, a close friend of Byron’s, related:

It was generally thought his halting gait originated in some defect of the right foot or ankle the right foot was the most distorted, and it had been made worse in his boyhood by vain efforts to set it right . . . The foot was twisted inwards, only the edge touched the ground, and that leg was shorter than the other . . .The peculiarity of his gait was now accounted for; he entered a room with a sort of run, as if he could not stop, then planted his best leg well forward, throwing back his body to keep his balance.8

Dr. Julius Millingen (1800–1878), his physician and early biographer, wrote:

…congenital malformation of his left [sic] foot and leg. The foot was deformed, and turned inwards and the leg was smaller and shorter than the sound one.5 (p. 143)

and commented:

The lameness…was a source of actual misery to him; and it was curious to notice with how much coquetry he endeavoured, by a thousand petty tricks, to conceal from strangers this unfortunate malconformation.

Byron was embarrassed by his deformity and made elaborate attempts to conceal it, wearing long baggy breeches. That it plagued him cannot be doubted, especially considering his acknowledged handsome appearance, prowess, and insatiable vanity.2,9,10 He told Dr. Millingen that as long as he lived, he would not allow anyone to see his lame foot.

The lameness, which he had from his birth, was a source of actual misery to him; and it was curious to notice with how much coquetry he endeavoured, by a thousand petty tricks, to conceal from strangers this unfortunate malconformation.

Byron himself described:

lameness as the greatest misfortune, and I have never been able to conquer this feeling…It requires great natural goodness of disposition, as well as reflection, to conquer the corroding bitterness that deformity engenders in the mind.11

On another occasion he remarked:

If THIS, (laying his hand on his forehead,) places me ABOVE the rest of mankind, THAT (pointing to his foot,) places me FAR, FAR below them.

Yet he was an excellent swimmer, famously swam across the Hellespont, and was an accomplished fencer, boxer, and horse rider. William Hazlitt’s 1815 essay On the Causes of Methodism suggested that the poet’s “misshapen feet…made him write verses in revenge.” Thomas Moore noted, “The lameness of his right foot, though an obstacle to grace, but little impeded the activity of his movements.”

There is much confusion in early accounts, some referring to a clubfoot on the right side, others on the left. However his mother Catherine observed in a letter of May 8, 1791 to her sister-in-law: “George’s foot turns inwards, and it is the right foot; he walks quite on the side of his foot.” His half-sister Augusta confirmed this, as did his Nottingham cobbler who made special boots for him. But the casts of his feet in the Nottingham Museum are symmetrical with no visible deformity, but his right boot was padded.12,14 Canon T.G. Barber, the vicar at Hucknall Parish Church, controversially examined his embalmed body when the tomb was opened in June 1938, noting “The feet and ankles were uncovered and I was able to establish the fact that the lameness had been of his right foot.”13

Thomas Moore wrote that “one of his feet was twisted out of its natural position, and this defect (chiefly from the contrivances employed to remedy it) was a source of much pain and inconvenience to him during his early years. The expedients used were under the direction of Hunter.”6 Matthew Baillie, who examined Byron’s foot in 1799, said, “The right foot was inverted and contracted as it were in a heap and of course did not go fully and flatly to the ground.”13

What was the nature of Byron’s deformity?

Of many portraits almost none clearly reveal his legs or feet. However, Joseph Denis Odevaere’s image of 1826 shows Byron on his deathbed; the right leg is covered by a large sheet, but the exposed left leg and foot betray no obvious abnormality.

Denis Browne caustically observed that analysis of all the evidence would do little beyond quite unnecessarily establishing the unreliability of the human mind.14

Edward J. Trelawny, in his 1858 book The Last Days of Shelley and Byron, recalled exposing his legs after death in Missolonghi:

I uncovered the Pilgrim’s feet and was answered—the great mystery was solved. Both his feet were clubbed and his legs withered to the knee—the form and features of an Apollo, with the feet and legs of a sylvan satyr.

However Marchand notes4 (p. 1238): “‘it is apparent that Trelawny was writing from memory of his earlier association with Byron rather than from observation of his corpse.” When Trelawny republished the work twenty years later he described only “contractures of the Achilles tendons;…except this defect his feet were perfect.” Trelawny was plainly “unreliable in the extreme.”4

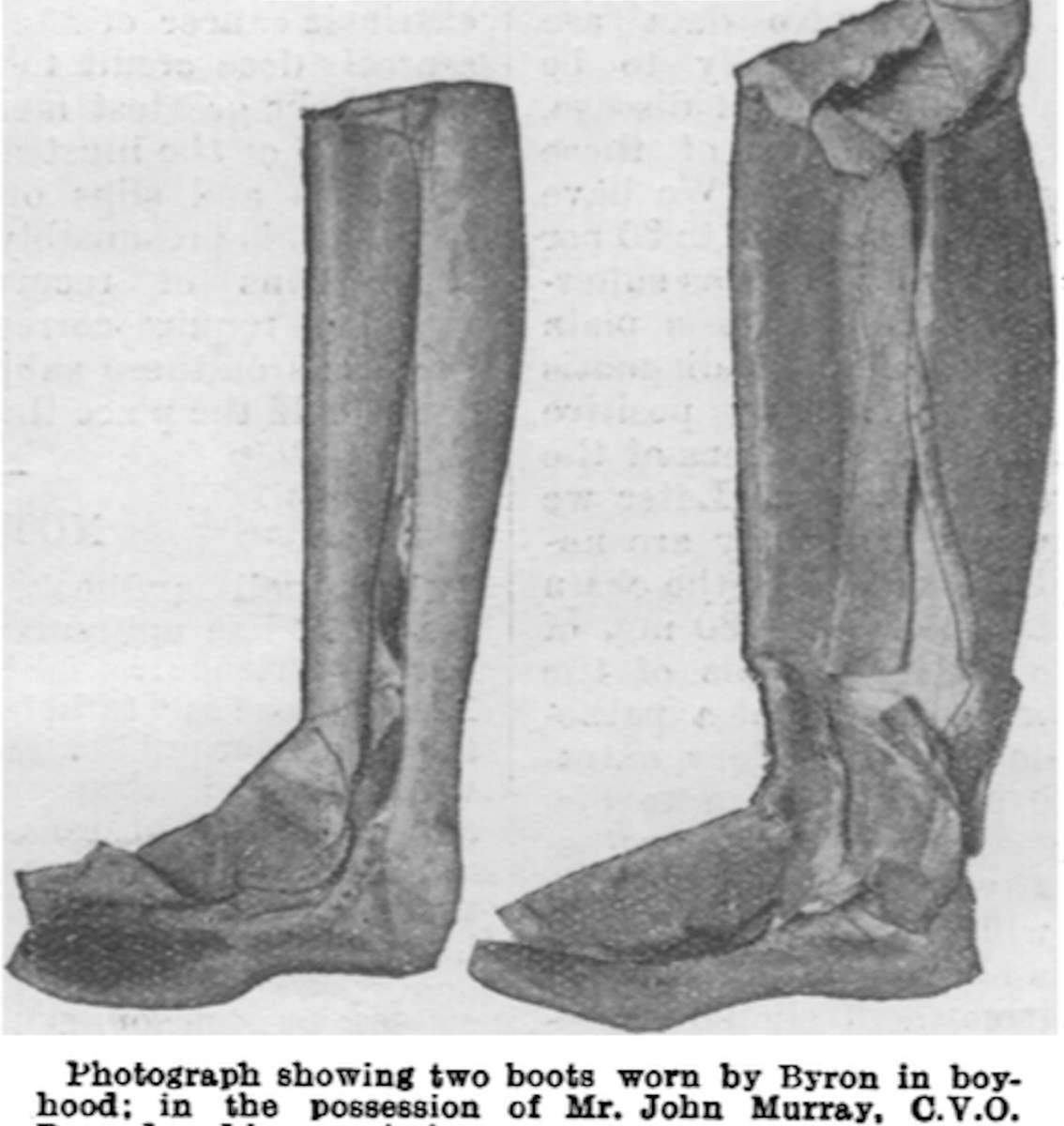

Various diagnoses have been suggested as the cause of Byron’s lameness including clubfoot, idiopathic dysplasia,15 poliomyelitis, and spastic cerebral diplegia (Little’s disease).14 Appraising his deformity and footwear (Fig 2.), Denis Browne pointed out many contradictory descriptions: “The boots were constructed not to correct the deformity but to disguise it, specifically with padding to augment a thin calf and a wedge to compensate for the abnormal foot.” These were based on photographs of the lasts on which Byron’s boots§ were made (in boyhood) at the Nottingham Museum.4 Browne also thought that “none of the treatment, painful and embarrassing though it was, that Byron suffered as a boy, could have had the slightest influence on his deformity.”

Unfortunately the deformity endured by Byron was described erratically and often unreliably by his contemporaries and thus remains a matter for conjecture. However, inspection of his shrouded body (Odevaere’s image of 1826: Fig 2) shows no evident wasting or deformity of the left leg and foot; the right is covered but the foot is sufficiently visible to exclude any gross equinus deformity of “clubfoot,” but suggests a mild metatarsus varus deformity as described by Browne.14 Its presence from birth rules out poliomyelitis. Browne concluded he suffered from a congenital dysplasia of the leg, but he too did not speculate about its cause. The variably described thinness of the leg and varus deformity suggest congenital pathology of the lumbosacral roots, the likeliest cause being spinal dysraphism.

The mercurial Byron lived a flamboyant life; he was sensitive, arrogant, vain, prone to debauchery, and given to affairs with married women, had a romance (and child) with his half sister Augusta, and engaged in homosexuality. Lady Caroline Lamb described him as “mad, bad, and dangerous to know.” But he was bold and heroic, not insensitive to social injustice and political controversy; he forged loyal, personal, and literary friendships with Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792–1822) and the irascible Leigh Hunt (1784–1859). The brilliance of his romantic poetry and wayward life spawned a host of biographies, notably Thomas Moore’s controversial Letters and Journals of Lord Byron, with Notices of his Life (2 vols., 1830), and John Galt’s The Complete Works of Lord Byron (1835). The standard life is Leslie Marchand’s three volume Byron: a Biography,4 revised as Byron: a Portrait, 1970.

Among his last recorded words were,

I have given [Greece] my time, my means, my health—and now I give her my life!—what could I do more?

At his death the Greek nation was overwhelmed by grief. Fifty years later Disraeli described him as “the most distinguished Englishman of the nineteenth century.” Perhaps the most perceptive appraisal of his complicated, mercurial personality was when Bertrand Russell, in his History of Western Philosophy, described him: “a man engaged in a tragic and romantic war against the Universe… His shyness and sense of friendlessness made him look for comfort in love-affairs, but as he was unconsciously seeking a mother rather than a mistress, all disappointed him except Augusta.”

In January 1824, shortly before his death, Byron shows his sadness and a sense of futility:

TIS time this heart should be unmoved,

Since others it hath ceased to move:

Yet, though I cannot be beloved,

Still let me love!

My days are in the yellow leaf;

The flowers and fruits of love are gone;

The worm, the canker, and the grief

Are mine alone!

He was thirty-six years old…

End notes

- * £500 is worth approximately £31,000 today.

- † Well portrayed in Sydney Box’s unpopular film The Bad Lord Byron (1949).

- ‡ Based on the opinion of Nolan D.C. Lewis, Pathologist and Neuropsychiatrist, New Jersey.

- § Byron’s orthopaedic boot, England, 1781–1810, Science Museum, London. broughttolife.sciencemuseum.org.uk/broughttolife/objects/display?id=92636

References

- The Cambridge Companion to Byron. Ed. Drummond Bone. Cambridge 2004.

- Rollin HR. Childe Harolde: Father to Lord Byron? British Medical Journal, 1974, 2, 714-716

- Baron JH. Byron’s appetites, James Joyce’s gut, and Melba’s meals and mésalliances. BMJ 1997;315: 1697-1702.

- Marchand Leslie A. Byron: a Biography (3 vols) New York, Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., 1957. Last accessed 29/3/2018

- https://archive.org/stream/byronabiographyv007277mbp/byronabiographyv007277mbp_djvu.txt

- Millingen J. Memoirs of the Affairs of Greece. London: John Rodwell; 1831; 8, 139-44. last accessed 29/3/2018: https://archive.org/stream/memoirsaffairsg01millgoog/memoirsaffairsg01millgoog_djvu.txt Moore T. The Life, Letters and Journals of Lord Byron. London: John Murray; 1837: 5, 15, 255–6.

- The Byron Chronology. In: Romantic Circles. http://www.rc.umd.edu/reference/chronologies/byronchronology/1778.html

- Trelawny EJ. Recollections of the Last Days of Shelley and Byron. London: Edward Moxon; 1858: 24, 224, 226.

- Sheldrake Timothy (the Younger.) Animal Mechanics applied to the prevention and cure of Spinal Curvature and other personal deformities. London, Published by the AUTHOR, Renshaw and Rush 1832.

- Gamble J. Lord Byron’s lameness. The Pharos/Summer 2016

- Lovell EJ. Lady Blessington’s Conversations of Lord Byron. Princeton (NJ): Princeton University Press; 1969: 80–2, 84.

- MacCarthy F. Byron: Life and Legend. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux; 2002: 10, 4.

- Morrison AB. Byron’s Lameness. Literature, History and Cultural Studies. 1975; 3: 24–31.

- Browne D. The problem of Byron’s lameness. Proc Royal Soc Med. 1960 June; 53(6): 440–2

- Cameron HC. The lameness of Lord Byron. BMJ 1923; 1(3248): 564–565.

JMS PEARCE, MD, FRCP, Emeritus Consultant Neurologist, Department of Neurology, Hull Royal Infirmary.