John Graham-Pole

Gainesville, Florida, United States

|

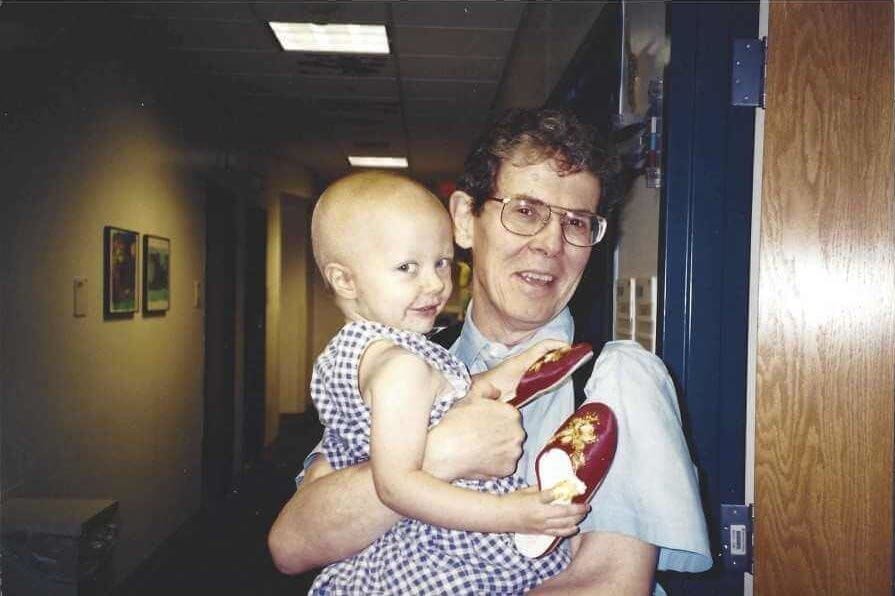

| Dr. Graham-Pole with cancer patient, Bridget. At the time of the photo, Bridget had life-threatening cancer requiring opioids, and is now a successful artist. Author photo. |

The poppy’s juice . . .brings the sleep to dear Mama

— Sara Coleridge, Pretty Lessons in Verse for Good Children

In Xanadu did Kubla Khan a stately pleasure dome decree

— Samuel Coleridge, Kubla Khan, penned on waking from an opium-induced dream

Of all God’s floral bounty, only papaver somnifera drips its beads of morphine, codeine, and papaverine from verdigris pods to bless, beguile, and curse us. The fragile poppy can bestow balm or bane: Heaven or Hell.

Paracelsus christened this elixir laudanum around 1520, but it wasn’t until the seventeenth century that Thomas Sydenham became its physician advocate. In the American Civil War, both Billy Yank and Johnny Reb came to embrace laudanum’s blessed succor—and its vicious lure.

For forty years, as oncologist and palliative care physician, I had the license to prescribe opioids to relieve unspeakable physical and emotional agony. I remember my very first prescription.

***

Internship, Bart’s Hospital, London, January, 1967

I peer at the X-ray screen showing the cancer clusters eroding Mrs. Lane’s L3-L5 vertebrae, encroaching on her iliac crests. As I nudge open the ward door toting her four-inch-thick chart, I contemplate the two precise Nightingale-style lines of beds, their occupants mostly motionless, loath to derange the apple-pie order. Not Mrs. Lane: jaw clenched, eyes screwed tight in a sheen of sweat, she is scrunching her pillows, scrabbling for a halfway comfy posture.

“Mrs. Lane, I’m the junior doctor. I have a few questions, and I need to carry out your examination.”

A stab at a smile. “Yes, doctor.”

“What brought you into hospital, I wonder?”

“Me backache.” An abrupt shift of buttocks. “Can’t ’ardly stand it.”

“How long has it been?”

“Real bad since Christmas.”

Stark dread stares back at me. She has to have figured things out, but I know to pussy-foot around the true cause, debar direct questions, keep the C-word off-limits. The universal view in 1960s Britain is that if you tell a patient outright they have cancer, you buy them a one-way pass on the non-stop express: destination death.

“Any other pains?”

“Me ’ips. But me back’s much the worst.”

“You’ve had an operation, I believe?”

“Yes, on me . . .” Left hand alights on right breast. Or where it once was.

“Ah, yes.” Name no names.

Foot-tapping behind me: the promised probationer nurse draws the curtains around us. My physical exam looks to be strictly limited; my questions have already exhausted Mrs. Lane. She writhes apologetically under my hand, breath caught against the pain. I tune into the parts I can reach without rolling her over, probe the jagged purple scar across her right chest, start to remove the bandage shielding her remaining breast. It is stuck fast.

“Something happening under here, Mrs. Lane?” I sense naming it will distress her more.

“Yellow stuff’s comin’ out.”

“I need to take a look.”

In the supply room, I assemble swabs, saline, and what is left of my composure. When I get back, the nurse is holding her hand as Mrs. Lane brushes away tears, makes another wordless attempt to smile. I bite my lip against my own eyes’ prick, moisten and free the bandage, eye the blood-red swelling and the pungent mustard ooze. Neither hot nor acutely tender; there is only one diagnosis. I slip my arm behind her spine. She lets free her first yelp.

“Sorry, doctor. Real sore there.”

Why must she apologize?

“I’ll be gentle as I can.”

Laying my fingers on each lumbar vertebra elicits a wince. My hand abuts jagged hardness below her right twelfth rib.

Is there nowhere this monster hasn’t ravaged?

“Does it hurt here?”

“Not like me back.”

A flash of fear, fast hidden. I stretch back as the nurse rearranges her nightie.

“They’re starting your X-ray treatments today. I’ll get you some pain medicine meantime.”

I have seen morphine given to patients with heart attacks; but never Brompton’s cocktail—that time-honored mix of heroin and cocaine said to work miracles with people at death’s door. All I had heard in medical school is how fast you can get hooked, become apneic in a heartbeat. No way.

Mrs. Lane is wheeled off for treatment, whimpering with each jolt of the gurney. After three days of this charade, the staff nurse takes me aside.

“D’you think the radiation will kick in soon?”

I risk sitting close by Mrs. Lane’s bedside, laying my hand on hers.

Is this against protocol?

“Are you doing any better?”

“Can’t say I am. They ’ad to cut me treatment short—couldn’t ’ardly ’old still.”

“Mostly your back still, is it?”

“Moved to me ’ips, too.”

I let my hand rest. Laying on hands just for diagnosis, isn’t it, not attempts at solace? So who am I trying to comfort?

Staff waylays me again. “What about Brompton’s? She’s got to get some relief—the radiation’s not touching it.”

“Isn’t Brompton’s just for terminal cases? And it might make it hard to tell if the radiation treatment’s working . . .”

“It’ll be fine, John. They leave all that stuff to you interns.”

Nice eyes, like she cares a lot. And it’s the first time anyone’s used my name.

“Thanks. I’ve been really worried about her.”

I check and re-check the precise dosage of this wonder-cocktail, write for the smallest dose, but at the nurse’s prompting make it three times a day.

“All the difference getting it regularly. And she’s in constant pain.”

What if I find her dead in bed in the morning?

I sleep restlessly, hurry to check on Mrs. Lane first thing. She greets me with a grin.

“Doctor, that cherry-tastin’ medicine, it’s really ’elpin’. I got to sleep easy. An’ I can move me legs more.”

“So pleased to hear that, Mrs. Lane. Not feeling too sleepy, are you? No dizziness? No trouble breathing?”

“Not a bit. Even ’ad an appetite for breakfast.” She winks. “An’ made it on the bedpan easy!”

Ten days later, the RT resident tells me her treatment is done.

“She seems a lot better.”

Not just your rads, buddy—wouldn’t explain her cheeriness and hearty appetite.

I order more Brompton’s for her to take home. Her husband arrives toting a battered suitcase.

“I must be certain you’ve got the dose right—it’s very strong stuff. Three times a day regularly, but no more. Make certain the doctors give you a refill whenever you need it.”

She grasps her husband’s hand. “I feel real chipper—got a ’ole new lease of life.”

Her husband chimes in. “I’ve got me missus back!”

They walk arm-in-arm out the door, cane abandoned by the chair, the only outward sign her pinpoint pupils.

***

I remember my very last opioid prescription, too.

Cedar Key, Florida, December, 2007: Final week as children’s hospice director

Dorothy and I gaze out over the Gulf, munching tilapia and chips. My pager beeps: Cendra, my hospice nurse.

“Sorry to bother you, John—I’m at Marie’s house. The little one with the glioblastoma. Her intracranial pressure’s got to be building again—she’s getting awful headaches. I need a stat order to up her morphine.”

This is a first—ordering intravenous opioids for a three-year-old from fifty miles distant.

“What’s she on now?”

“Two milligrams every four hours—I want to go to three.”

“Good, and another milligram in ten minutes if she needs it.”

Another beep on our way home to Gainesville.

“She’s sleepy but still awfully restless. Can I go up?”

“What weight is she?”

“Fifteen kilo.”

I do some quick calculating. We are already at twice the standard IV dose of 0.1mg/kg. But what is there to lose? At my last house call, her parents were almost begging me to help Marie rest in peace.

“Let’s go with four milligrams, and another two every thirty minutes. I’ll join you as soon as I’ve dropped Dorothy.”

Forty minutes later, there is desperation in the nurse’s usually unruffled voice.

“How long can she hang on, John? She’s barely rousable, but still jerking and moaning. Pharmacy here is down to their last IV dose—the van’s heading out with supplies.”

“I’ll be there in twenty minutes. Five milligrams every ten minutes till then.”

As I open the living room door, Mom is holding Marie in her arms, while Dad and Cendra cradle Mom. Marie is at rest.

“Five minutes ago, John. What a blessing.”

Marie’s mother’s last words leave me with no doubt we had done the only right thing.

“Thank you both for ending our little one’s misery.”

It was Cendra who had done all the heavy lifting. Not for the first time, I offer silent thanks for Florence Nightingale’s blessed daughters.

***

Papaver Somnifera—tincture of opium: God-given blessing, and the Devil’s curse. With boundless power to shine the light of good and spread the dark of evil. To inflict physical, psychological, and spiritual torment, and to assuage it. We embrace its healing balm while our youth yields to its iniquity.

Between my first and last opioid prescriptions, an epidemic erupted—unimaginable to my Therapeutics mentors. 64,000 Americans died from opioid overdoses in 2016, compared with 3,000 in 1970—exceeding deaths from guns, traffic accidents, and the Afghanistan and Iraq wars combined. Few medical schools offer adequate training in managing pain, or addictions. I was self-taught—by guess and by gosh. Oral, rectal, intramuscular, intravenous, sublingual, subcutaneous, transcutaneous—how many opioid prescriptions did I order over my forty years of practice? How much suffering did I assuage? How many addictions did I trigger?

My answers: countless; much; none that I know of—by the grace of God.

JOHN GRAHAM-POLE is a professor emeritus of pediatrics, oncology, and palliative care from the University of Florida. He has published, co-edited, and contributed to six books on children, arts-in-medicine, cancer, and poetry, including Illness and the Art of Creative Self-Expression (New Harbinger, 2000) and Whole Person Healthcare Volume 3: The Arts & Health (Praeger, 2007). He has written several hundred book chapters, essays, short stories, and poetry, and given keynote presentations in North America, Europe, Asia, and South America. His memoir will be published this summer. He co-founded Arts in Medicine, the Center for Arts Medicine, and Arts Health Antigonish.

Winter 2018 | Sections | Doctors, Patients, & Diseases

Leave a Reply