Tolani Olonisakin

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA

|

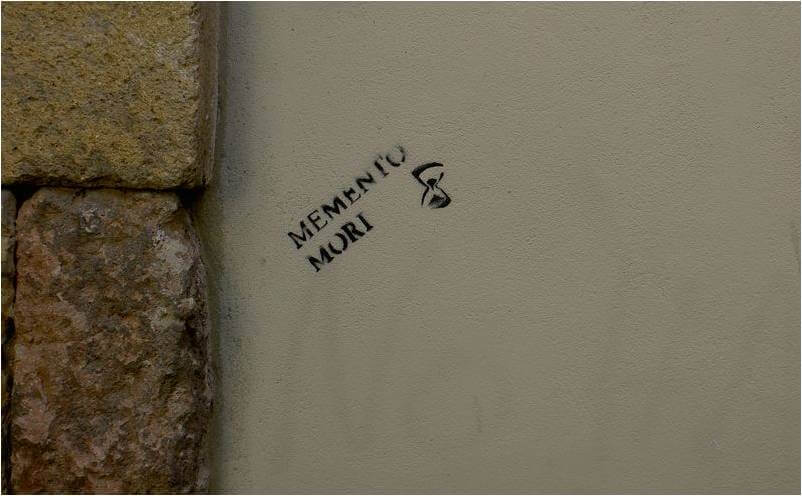

| Memento mori, remember death. Photo Credit: Southtyrolean, Stencil art. Seville, Spain. |

Six weeks after I turned eighteen, I lost my father. I was told he died of a cardiac arrest. One minute he was reading the morning paper, and the next minute he lay sprawled across the living room floor, lifeless and inanimate. I had not seen the man in two years; in fact, we had spoken the night before he died and planned an upcoming visit in December. Losing my father was one of the hardest things I ever had to come to face. I was shocked, heartbroken, and even a little enraged. I was all the more hurt that I could not be with my family at the time, as they were five thousand miles away on the other side of the Atlantic. Initially, I tried to be alone and evaded the topic as much as I could. I reasoned that the less I talked about it, the more I would be able to concentrate on schoolwork and pull through that semester. Of course, I was wrong. The few times that I did let people in, shared my grief, and talked about my angst were vital in achieving academic success that semester. I saw first-hand that it is amazing how much you can accomplish when you are willing to admit your weaknesses and embrace the strength of others.

Two weeks before my twenty-fifth birthday, I lost my first patient. Sixty-six-year-old “Jennifer” was dying of disseminated epithelial ovarian cancer. I was the medical student and, by far, the least experienced member of the palliative care team. It was only the fourth day of my family medicine clerkship in a rural town. Jennifer’s daughter was visibly shaken and directed a barrage of questions at our team. How much time did her mother have left? How were we confident that her mother was not in significant pain? How could we be certain that death WILL occur? I did not have any real answers to her questions. And yes, death did occur, but I was fortunate to be surrounded by a team of experts. Together we revisited the goals of care, reassured the family in a private meeting, and facilitated closure. Jennifer’s daughter—and her son, sister, and nephew—seemed at peace with the resolution.

It is hard to say which is more painful—facing the sudden loss of a loved one or watching a beloved wrestle death slowly, painfully, and defiantly. I have experienced the former and I can only imagine the latter. To watch someone hang on for dear life and hold on to every precious memory; vacillate between wanting it all to end, but not wanting to let go; to pine for hope, for restoration, for love—all that must be terribly excruciating. It is amazing, liberating even, how much everything else pales compared to death: the job you wanted so badly, the house you fought tooth and nail to keep, the cars you were certain would move you up the social ladder, those really nice shoes. Death changes your perspective. You no longer hold on to your bitterness, and you let go of the manifold grudges that have narrowed your perception in the past. Your multiple goals coalesce into one—to live.

What were Jennifer’s thoughts as she closed her eyes and soaked it all in? Did she race through the story of her life? Did she comb through every image, searching for things she could or should have done differently? Did she question life after death? Did she even care? What about her family? Sometimes it is harder to watch a loved one suffer through pain than to experience the torment ourselves. We imagine the worst and cannot possibly piece together any hope the sufferer might see. Those left behind may be marred permanently, and often the sufferer and the loved one are both in tremendous pain.

Anatomy class marks a medical student’s foray into discussions about death. It is here that we first learn to mask our feelings and bottle our emotions: the nervousness, the anxiety, the thoughts that the body on the table may very well belong to a cousin or a sister. The uneasy feelings are buried under “professionalism” the moment we make our first incision. We teach ourselves the mantra, “You’re in medical school now, so think like a physician and act like one.” And even though we are reminded countless times about the importance of empathy, sometimes, it gets drowned in the “46-year-old male with sore throat and fever . . . and possible ADP-ribosylation of elongation factor 2.” We slowly begin to see patients merely as cases and get excited (rightfully so) when we can finally nail the diagnosis. But empathy, while sometimes challenging, remains an invaluable tool in medicine. In the few patient interactions I have had so far, I have observed an interesting trend in my own responses. When I am poised to make a diagnosis and all I can think of is the incredible presentation I want to make to my facilitator, I miss salient points and can barely remember the patient’s name. On the other hand, when I take the time to listen, to observe changing facial expressions, or to share a joke, I learn a lot about my patient and surprisingly, I learn a lot about myself.

TOLANI F. OLONISAKI is an MD-PhD candidate in the Medical Scientist Training Program at the University of Pittsburgh and Carnegie Mellon University. Born and raised in Nigeria, she came to the United States in pursuit of higher education and graduated summa cum laude from Fisk University with a Bachelor of Arts in Biology. Upon completing her training here in the States, Tolani intends to work with other like-minded physician-scientists in securing funding for sophisticated medical and research equipment in Nigeria (and hopefully, much of Western Africa).

Winter 2018 | Sections | End of Life

Leave a Reply