Bert Hansen

New York, New York, United States

|

| Figure 1. Frame of Christiaan Eijkman in Java considering the dietary difference between polished and unpolished rice, from The Magic Alphabet © MGM 1942. All rights reserved. |

Some of us are old enough to remember long Saturday afternoons in neighborhood movie theaters, where we were entertained not only by the feature films, but also several one-reel shorts that filled out the program. These included newsreels, travelogues, cartoons, little comic dramas, documentaries, and re-enacted stories from history. The history shorts were not documentaries, but highly condensed narratives.

Only a few will probably remember the black-and-white medical history shorts released by major studios, primarily MGM and Warner Brothers.1 Who would have pictured teenagers coming to see a Western or a war movie as the audience for The Story of Dr. Jenner (1939), about the invention of vaccination, or the Romance of Radium (1937) about applying Madame Curie’s discovery to medicine? It is likely that each movie was seen by a million people or more; that is orders of magnitude larger than medical history’s readers or viewers today.

These films, products of the medical humanities before that phrase was used, were not made for schools, even though some later received educational distribution. With high production values, they benefited from all a studio’s resources for research, costuming, choice of actors, and especially direction. The major studios used them to test out promising talent before giving them big projects. The most famous of the directors of the medical history shorts was Fred Zinnemann, whose later career included such masterpieces as High Noon, From Here to Eternity, Oklahoma, A Man for All Seasons, and Julia. The first Oscar of his long career was for his film about Ignaz Semmelweis, That Mothers Might Live (1938).

Who else from the medical past was featured in these little narrative gems? Angel of Mercy (1939) told the story of Clara Barton and the American Red Cross; this MGM film was reissued in 1942 as Flag of Mercy with new material connecting it to the current war. The Magic Alphabet (1942) showed the research of Christiaan Eijkman in Java, where he discovered that beri-beri was a dietary-deficiency disease. (See Figure 1.) In Man’s Greatest Friend (1938) we meet several dogs used in medical research, starting with Louis Pasteur’s successful work on a vaccine for rabies.

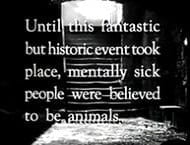

In One Against the World (1939), Dr. Ephraim McDowell faced the risk of a lynch mob when he decided to perform an unprecedented operation to remove an ovarian tumor. Although this took place in 1809, decades before the introduction of anesthesia or antisepsis, his extraction of a 7.5 pound tumor was successful, and the patient lived another thirty-three years. Philippe Pinel is the hero of Stairway to Light (1945) for removing restraints and introducing enlightened treatment into a French insane asylum in 1793. (See Figure 2.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Figure 2. Frames from Stairway to Light © MGM 1945. All rights reserved. | ||

Fifty years after Pinel, in 1847, Ignaz Semmelweis in Vienna made a spectacular discovery that puerperal fever could be largely prevented by adequate washing of doctors’ hands before examining parturient women. His struggle to figure this out and the resistance to his new procedure are efficiently conveyed in That Mothers Might Live (1938). Front and center is the mental decline he suffered from the opposition that would hold sway until the later discoveries of Pasteur and Lister about germs. All this drama in just ten minutes! The research work of doctors Banting and Best to make possible insulin therapy for juvenile diabetes around 1920 is the subject of They Live Again (1938). Dr. David Bruce’s discovery of the role of the tsetse fly in sleeping sickness around 1900 in Uganda is shown in Tracking the Sleeping Death (1938).

My own favorite among these films is A Way in the Wilderness (1940) about public health service doctor Joseph Goldberger’s investigation into pellagra, so prevalent among the poor in the American South. Not only did he face cultural and bureaucratic obstacles, but he had to surmount a huge intellectual obstacle in the medical profession’s insistence that germs were the cause of the disease. He pursued the germ as hard as anyone, but finally discerned that diet could explain a deficiency that led to the symptoms of rashes, lethargy, mental instability, and even death. First, he demonstrated this with an experiment on healthy prisoners, who were each promised a pardon if they were willing to eat only pork fat, cornmeal, and molasses—as much as they wanted—the common diet of the Southern poor. In the film we get to see how this limited diet in a controlled situation produced the ailment’s visible symptoms. Second, he injected himself, his wife, and his assistant with blood from pellagra patients to prove there was no germ transmission. Goldberger did not discover the mysterious factor that came to be known as Vitamin D, but he learned he could reverse the symptoms cheaply and efficiently with ordinary brewer’s yeast, saving hundreds of thousands of ordinary Americans from dead-end lives. (See Figure 3.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Figure 3. Frames from A Way in the Wilderness © MGM 1940. All rights reserved. | ||

|

|

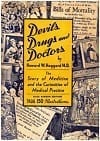

| Figure 4. 1929 dust jacket and 1953 paperback cover for the enduringly popular book Devils, Drugs, and Doctors. |

|

Most of these medical discoveries were based on methodical research, and many required these Hollywood heroes to overcome fierce resistance to their new ideas. This simple historiography seems very old-fashioned today when we emphasize complexity and context in historical narratives and pay great attention to social and institutional factors in scientific work. But it was the common approach in the first half of the century, especially in popular books like Howard W. Haggard’s oft-reprinted Devils, Drugs, and Doctors (1929). (See Figure 4.)

While these films might seem to be just odd little remnants of the past, they are in fact further evidence of the great popularity of medical history in mass culture seventy-five to a hundred years ago.2 It was a fertile era for the medical humanities, a time before medical history retreated into medical school curricula and graduate schools, where it survives today, highly professionalized but largely outside of public notice.

It would be gratifying to conclude by referring to a modern compilation of these films on DVD that you might find in a public library or order on-line. Unfortunately, copies are very rare.3 But it is possible to catch these films from time to time on cable channels, especially Turner Classic Movies (TCM).4 For researchers, copies of most of them are accessible on site in the UCLA Film and Motion Picture Collection.

Like all historical sources, these shorts preserve their own era in a unique way. For them, the world was black and white, both photographically and interpretively. The acting was less naturalistic than we are used to seeing; but the storytelling skills of the script, direction, and camera work have not been surpassed. Simplification was necessary given how brief they are, but the key developments remain clear, even when the film covers many years of a biography. They are honorable and estimable products of early cinema, fascinating to view for themselves as well as for the sake of historical understanding.

End Notes

- Two important works looking at this genre gave little attention to the medical stories: Richard Ward, “Extra Added Attractions: The Short Subjects of MGM, Warner Brothers, and Universal,” Media History 9:3 (December 2003), 221-244; and Leonard Maltin, The Great Movie Shorts: Those Wonderful One-and Two-Reelers of the Thirties and Forties (New York: Bonanza Books, 1972).

- My book has documented the substantial place medical history occupied in American culture from the 1920s to the 1950s, with attention to magazines and newspapers, feature films, radio dramas, commercial advertising, children’s comic books, and Life magazine. See Hansen, Picturing Medical Progress from Pasteur to Polio: A History of Mass Media Images and Popular Attitudes in America (Rutgers, 2009). Two recent studies of mine that further enlarge the picture are: “Medical History’s Moment in Art Photography (1920 to 1950): How Lejaren à Hiller and Valentino Sarra Created a Fashion for Scenes of Early Surgery,” J Hist Med Allied Sci. 72:4 (Oct 2017), 381-421, and “Medical History as Fine Art in American Mural Painting of the 1930s” (forthcoming).

- I know of only two medical history shorts released on DVD, in both cases as a minor extra along with the feature film. The Picture of Dorian Gray (Warmer Home Video, 2008) included Stairway to the Light, and Madame Curie (Warner Home Video, 2007) included Romance of Radium.

- Home-made VHS recordings of medical history shorts from broadcast and cable television, starting in the 1980s, have been donated to the Medical Historical Library of the Cushing/Whitney Medical Library of the Yale School of Medicine as part of my collection of medical prints; for further information see https://library.medicine.yale.edu/historical/hansen (accessed January 8, 2018).

BERT HANSEN recently retired after forty years of teaching at Binghamton University in New York, the University of Toronto, New York University, and the City University of New York and was twice in residence at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey. In 1985, he published Nicole Oresme and the Marvels of Nature, and in 2009, Picturing Medical Progress from Pasteur to Polio: A History of Mass Media Images and Popular Attitudes in America, which was honored by the Popular Culture Association and the American Library Association. His current research is centered on Louis Pasteur’s life-long passion for the fine arts.

Winter 2018 | Sections | Women in Medicine

Leave a Reply