Lesley Campbell

Darlinghurst, New South Wales, Australia

This is my account of three generations of women doctors in my family who in different times and different places were subjected to persecution or at least discrimination because of their race, religion, and gender. The account is written in the hope that society in general and medicine in particular will embrace a more tolerant attitude, and that increased participation by women in the professions will help promote this aim.

My story begins with my grandmother, Erna Stramf, born in Hungary in 1890, and at the time one of the few woman doctors in that country. Her parents had sent Erna to study medicine at the university because they had no money for a dowry for her to marry. In medical school, before graduating, she met and married a renowned Hungarian bacteriologist who discovered the typhus serum.1 Unfortunately he died young in the 1918 influenza pandemic, leaving my grandmother with a three-year-old child, my mother, Clara. During World War I my grandmother sent the child to stay with her sister and worked in military hospitals. A surviving photograph shows her in a white coat surrounded by Hungarian and Bosnian soldiers.

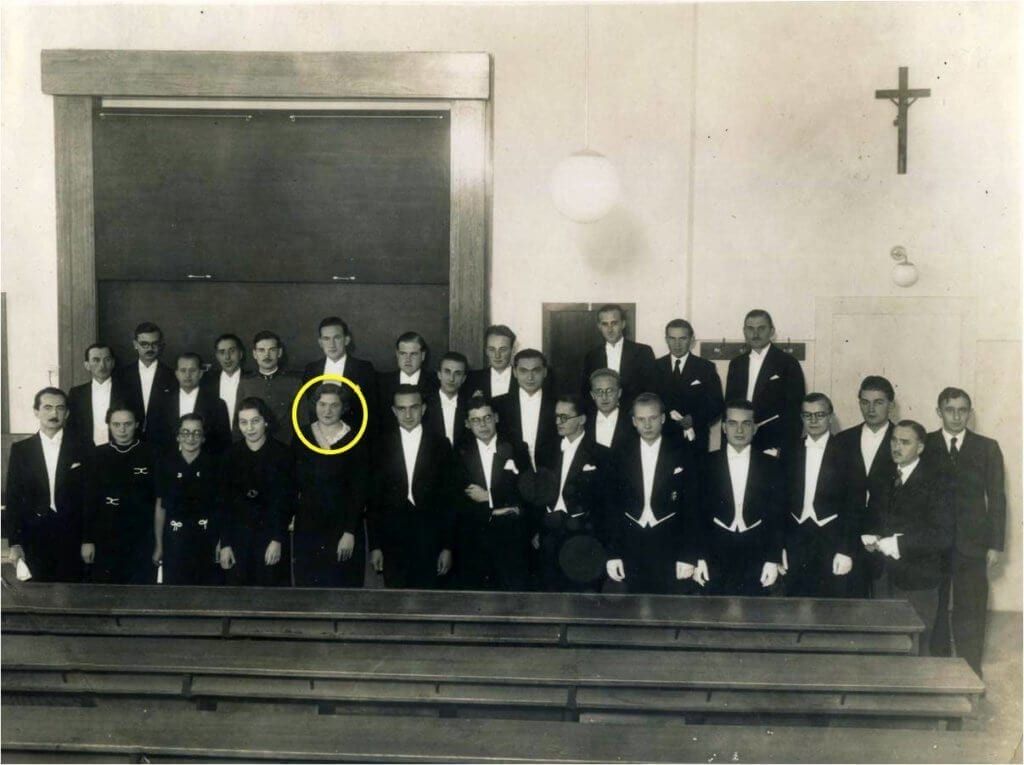

Erna subsequently met and married a lawyer, and spent time helping him in his practice. When my mother Clara turned sixteen she declared she wanted to become a psychiatrist. She was admitted to medical school, even though at the time only ten percent of positions in medicine were allocated to women. At age nineteen, in her third medical year, Clara married my father, a solicitor. She won the pathology prize in fifth year medicine because the papers sent to the examiners were marked anonymously, showing not the student’s name but only a number. This was just as well, because the grumpy professor hated women and would have never knowingly give the top mark to a female.

Medicine as practiced between the two World Wars was still somewhat primitive. Few effective medications were available. Leeches were still being used for a variety of conditions. Clara remembers how on entering her mother-in-law’s bedroom one day she was greeted by several leeches working their way across the floor towards her. Leeches were used to treat hypertension—and my mother has noted that her mother-in-law lived another thirty years despite, or perhaps because of the leeches. She also remembers that the Wasserman Test for syphilis was done on all new patients and was often positive, but there was no penicillin available yet. Sulphonamides had only just come into use. In some instances they would turn the patients’ lips blue. This would alarm the surgeons when my mother was giving anesthetics, leading them to think the patients were dying—but the “cyanosis” usually wore off.

Clara graduated in medicine in 1937 and took a country hospital job, but her husband was called up into the army as war was looming. She visited Vienna and saw with horror Adolf Hitler parading down avenues of excited people singing his praises. My parents sacrificed much to escape from Hungary, my mother losing a pregnancy, but other members of the family could not get out.

My grandmother found herself trapped in Budapest and served as a doctor in the ghetto. What she saw there she never told me; but I remember that when I did not want to finish my sandwich and hid my crusts behind the couch, she found them and impressed on me that food must never be wasted: she had seen too many children starve, crying for a crust of bread.

Then one day the Nazis came to take her husband to a concentration camp. She ran after him, crying, begging them not to take him. They said, “You want to come with him?” She never saw him again but was told by a survivor that he died in the “cattle truck” on the way to camp. My other grandparents were able to purchase forged christening certificates renaming themselves “Joseph” and “Maria,” which may have saved their lives while hiding with their daughter in Hungary.

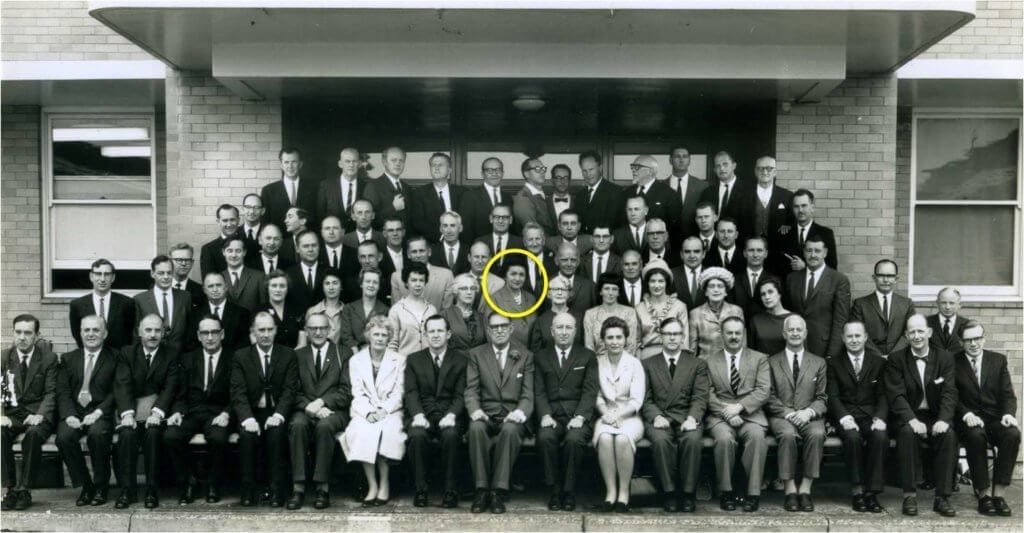

My parents reached Australia in December 1939. To her dismay Clara found that her medical degree was useless in Sydney. She eventually moved to Brisbane, where after preliminary studies in anatomy and physiology she was allowed to complete a three-year course in medicine. During that time she lived in a boarding house while my father continued to work in Sydney. She had a lonely time and people living there we not at all friendly to foreigners. After graduation she worked as a medical officer in a Brisbane hospital, and was regularly sent to compulsory war-time country locums, replacing absent doctors, seeing poliomyelitis epidemics before preventative vaccines were available. She later went to a country practice, staying there three years, coping with snakebites and injuries.

Clara finally attempted to fulfill her old dream of becoming a psychiatrist. At first she was told that this could not be done; but one year later a position unexpectedly opened for a psychiatrist in an old-style asylum for mentally ill patients and “mentally deficient” children. Conditions there were appalling. Chronic patients were confined to total bed-rest, developing non-healing bedsores because of immobility and weakness. She got them up and mobile, and they started to heal as well as improve their overall health.2 After three years Clara went to Sydney to work in a large mental hospital in order to obtain her specialist degree. With her husband and daughter she remembers living in a little two bedroom flat above a male ward, with loud nightly snores and harsh coughs coming from the ceiling. These came from possums living in the roof. They accepted the noise once they realized what it was, and adopted a baby possum found by a nurse in a rubbish tin. He lived with the family and came for dinner nightly when his name was called.

With little drug therapy and minimal psychotherapy, my mother (“lowest on the totem-pole”) was rostered to administer thirty “shock treatments” at 8 am twice a week. The chronic wards were full, but my mother worked hard with patients and their families, and several “long-stayers” were able to leave the hospital: grateful families still keep in touch. At her oral exam, she was asked personal questions (including which country she came from) by one of the examiners, who told her she had failed the test. It was only the honesty of the other examiner, whom she contacted at my father’s insistence, who said she had passed but the other examiner had tried to have his own registrar receive a pass-mark instead of the foreign woman. The pass was verified in writing and my mother dared not complain about the incident.

Tragically my father died suddenly of a heart attack in his forties in 1957. My mother decided to move from the mental hospital into her own house and start a new phase in her life, entering a newly evolving area: child guidance. She resolved to handle the little patients the only way she knew, with love and support, playing with them and giving them non-judgemental love, while also trying to help parents and schools support the “offending” children. She had a long and successful career in child guidance, observing that the treatment was often not for the children but their parents.

She received a Churchill Fellowship to study the new area of child guidance in the UK and USA, then continued to teach in clinics at several hospitals before retiring to private practice. Some patients were so grateful for her help that they returned for many years. She gave special support to those who were refugees from war.

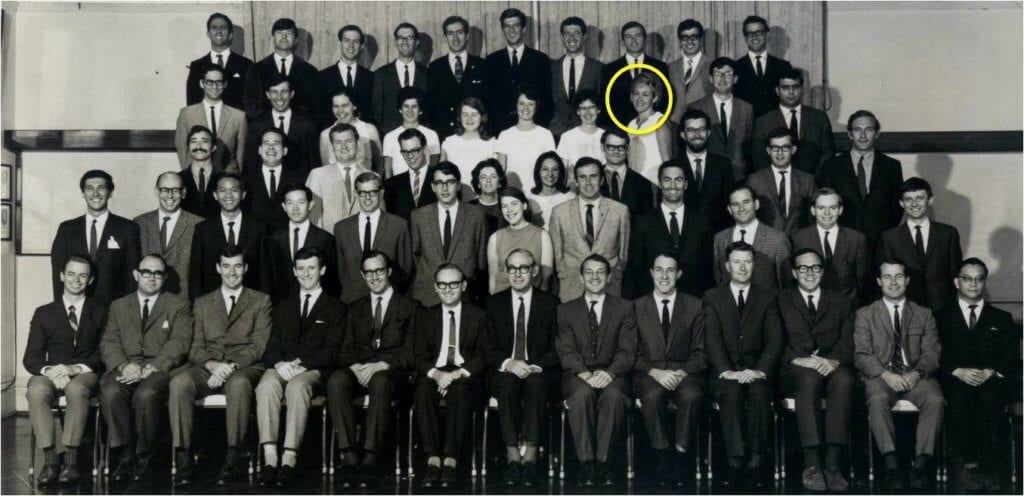

My own path to a professorial position, despite the increasing acceptance of women into medicine, has still been marred by prejudice, sexual harassment, and even physical bullying. I have had an attending physician doctor grab me by the lapels of my white coat and shake me to enforce what he said! Patients often think I am the dietitian, and my young registrar is taken for the professor because he is male. I never reported the sexual harassment when I was young by senior clinicians who are now world famous. I see a need for more “feminization” of medicine: moving from a competitive model with targets and quotas to a more empathetic and caring approach to both our patients and our colleagues.3

References

- Csernel, E and Marton A Die Behandlung des Typhus abdominalis mit nicht sensbilisier Vakzine. Separatabdruck aus der Wiener klinischen Wochenschrift:1915, Nr 27.

- Elmoos, L. Beneath the Pines. A History of Stockton Centre 2010, p68-69.ISBN 978 0-9752356-4-5.

- Our patients will always remain with us: that is what experience means. Campbell LV. Lancet 2006; 367: 1626-7.

LESLEY CAMPBELL, MBBS, FRACP, FRCP, is Senior Endocrinologist at St. Vincent’s Hospital and Professor of Medicine at University of New South Wales. She has published over 230 papers, books, and manuals; chaired and served on national and international committees; and is a past President of the Australasian Obesity Society. She writes teaching material for the public and professionals and has served as consultant to lay diabetes groups. She was awarded the Swedish Society of Medicine Medal and the Sir Kempson Maddox Award. She has spoken in Denmark, Sweden, Thailand, and Malaysia about diabetes and researches gender gaps in the treatment of cardiovascular disease and diabetes, and the unmet needs in diabetes distress and depression.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 15, Issue 3 – Summer 2023

Leave a Reply