Annette Tuffs

Heidelberg, Germany

|

| Alfred Doblin. Copyright S. Fischer Verlag |

“And when I came back – I did not return. You are never the same person you were, when you left.” Thus wrote Alfred Döblin (1878–1957) in 1946, in the newspaper Badische Zeitung in Freiburg,1 a few months after ending his forced absence of twelve years in France and California. The German novelist and psychiatrist found his country in ruin and deep disarray. Nobody took notice of the return of the author of Berlin Alexanderplatz,2 the novel that had gained him worldwide fame in 1929. Only four years after this success, Döblin had managed in the nick of time to escape the Nazis, avoiding prison and the sight of his books burning along with the works of other Jewish authors—an unmistakable portent of the horror that was to come.

But in 1946 Döblin also had to realize that you cannot come back when the place you return to has also changed. Precious memories of places and people were tainted by the painful reality of what happened in his absence. The novelist Döblin was hurt by the disinterest in his work and the consignment of his person to oblivion. The psychiatrist Döblin was stunned by his discovery that the Nazis had not stopped at destroying his books, but had also turned on the patients he used to treat as a young doctor.

More than 70,000 mentally ill patients, adults and children, were killed in Germany by euthanasia under the Nazi regime. The full extent of the mass murder—named “T4 action” after the headquarters at Tiergartenstrasse 4 in Berlin from where it was coordinated—only unfolded much later. In 1946, though the practice of euthanasia by the Nazis was known, there was little more proof than individual stories of relatives and hospital personnel, and little interest in the issue.

Döblin was aware of the euthanasia. During a trip to the Black Forest—he had previously lived in nearby Baden-Baden—he met a former colleague who gave him detailed insights into the procedures of the mass killing and the suffering of the patients. In 1906-1908 the two young psychiatrists had both worked at the psychiatric hospital in Buch, on the northeastern outskirts of Berlin. Talking to Döblin, the colleague, who Döblin left unnamed, tried to unburden his heart from burning feelings of guilt.

The psychiatric hospital in Berlin-Buch had been built at the beginning of the twentieth century. Comprised of forty individual buildings with a sympathetic architecture and spaciously laid out in expansive gardens, it was the prototype of a modern, patient-friendly hospital, housing several hundred patients. Döblin drew from his experiences in Buch and used them as a scenario for Berlin Alexanderplatz. There in the book it happens: the famous absolution and recreation of the protagonist Franz Biberkopf, who escapes death and is eventually turned into a new human being—despite rather than because of his medical treatment.

In 1946 the hospital in Berlin-Buch once more became the setting for Döblin’s writing, not exactly in the same literary genre, but just as moving as his novel. He documented his colleague’s confessions, turning them into a literary report for a newspaper. Therein, one can read that the terrible events started in 1940, when doctors were told to prepare lists of patients who had stayed longer than five years and would presumably never be dismissed. Starting with forensic patients, the evacuation in big lorries under the eyes of SS officials began. But where were they being taken to, asked Döblin’s manuscript—nobody could tell.

Döblin describes the transport in vivid and haunting detail: “Can you see the old woman, who has been pushed out of the door onto the pavement. Her head is askew and she purses her lips. On her disheveled hair she carries an ancient crumpled hat. She seems to like her position, which she has assumed in that moment: one arm firmly pressed to her body, the other one horizontally raised at her eyes height. She has to be pushed, step by step and carried up the stairs to the car.”

|

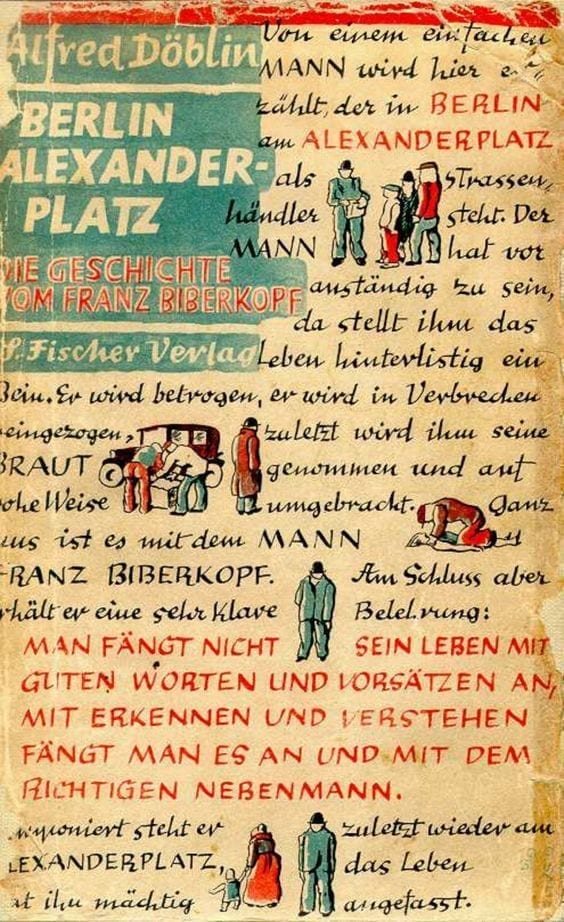

| Original Cover of “Berlin Alexanderplatz” by Alfred Doblin S. Fischer Verlag, 1929 |

Döblin describes how the relatives of the transported patients began to ask questions, but nobody was able or wanted to answer. Eventually they were told that the psychiatric hospitals were needed for the wounded and acutely ill, and that the psychiatric patients were being taken away to be treated in provincial hospitals.

Döblin goes on: “Slowly, the information leaks through where this journey into the blue really ends… There is shouting in the treatment rooms and the corridors: Murderer! You are murderers! Obstinate relatives are sent to the medical authorities. And then they are sent back to the hospitals, and from there back again, until they give up.”

The article describes how the patients, hearing the horrible rumors, tried to escape from the hospital. And how the nurses were ordered to perform the dreadful task of marking those of their patients who were on the list by branding names on their skin, like pigs. The nurses “complain but do what they are told – with tears in their eyes.”

Then the patients were brought to their final destinations: the shower rooms. Döblin writes: “They have to sit on benches. One of them prefers to stand in the corner, another one sits on the floor. The caretaker says: Be quiet, just wait! And she closes the door. The patients are now on their own. One of them starts her habitual little walk round. Another one whispers and shouts at something invisible. Then the sweeping sound of the shower starts…”

As to why there was no resistance from the doctors, Döblin writes: “They just follow the orders based on the “Führer’s will.” And: “The old Romans pushed people older than 70 from a rock.”

At the end of their conversation Döblin’s penitent tells him another truth. “We also have a weak son at home. Because we wanted to save him, we hid him and brought him to strangers. Every time I prepared a list it felt like signing the death sentence for my own child.”

Döblin sent his article to the Badische Zeitung. At first the editor was not interested. Several weeks later, on 3 May 1946, it was published under the title “The Journey into the Blue.”3 It drew little attention. This was the first literary report about Nazi euthanasia, written by an author who in an essay “Doctor and Poet” published twenty years earlier had stated: “I worked as a junior doctor in several asylums. There, I always felt very comfortable in the company of patients. In fact I noticed, that… I could only stand two categories of human beings: children and the mentally ill.”4

Publishing articles and broadcasts on the horrors of Nazi Germany and the Nuremberg trials was one of Döblin’s occupations after his arrival in Germany. Döblin and his wife Erna made their new home in Baden-Baden. As a persecuted emigrant who had always openly attacked the Nazi regime, he was given the job of a cultural officer for the occupying French army, which entailed judging manuscripts as to whether they were politically fit for printing.

Sadly Döblin, then already seventy years old, had no chance of returning to his primary professional vocation as a psychiatrist, which he had always, despite his phenomenal early success as a part-time novelist, preferred to his literary occupation. “Why did I study medicine? Because I was seeking a truth which was diluted by philosophy.” Medical practice was to him a “profound, honorable, but humble profession.”5 It was also a continuous source of artistic inspiration, for instance causing him to ask “what was the difference between a fantasizing patient and a fantasizing writer?”

Could he not bear to go back to Berlin? His new home was in South Baden and not in the town which had once inspired him to write his best known novel. He visited Berlin, but did not stay. However, South Baden was not entirely foreign to him since he had spent several years as a medical student at Freiburg University. His dissertation had already addressed a psychiatric problem concerning memory losses due to Korsakoff psychosis.

Döblin’s supervisor for that work was the well known Freiburg psychiatrist Alfred Hoche (1865–1943). Later, in 1920, Hoche, together with Karl Binding, a lawyer at Freiburg University, developed an argumentation—financial and moral—for euthanasia in his treaty “Allowing the destruction of life unworthy of living,” which Döblin, therefore, presumably knew.

In 1953 Döblin returned to Paris, where he had spent the first years of his exile. His last novels had not found the appeal he had hoped for, unlike writers like Gottfried Benn and Ernst Jünger, who were lenient or ambivalent towards the Nazi regime, were publicly celebrated. He was unjustly reduced to Berlin Alexanderplatz.

After a heart attack and the onset of Parkinson’s disease, he was taken into care by German hospitals and died on 26 June 1957 in the psychiatric hospital in Emmendingen near Freiburg—amongst the patients he had always cared for most, as doctor and as writer.

References

- Christina Althen: Alfred Döblin, Leben und Werk in Erzählungen und Selbstzeugnissen, Als ich wiederkam, Artemis & Winkler Verlag, Düsseldorf, 2006, ISBN-13:978-3-538-07001-1

- Alfred Döblin: Berlin Alexanderplatz, S. Fischer Verlag, 1929

- Christina Althen: Alfred Döblin, Leben und Werk in Erzählungen und Selbstzeugnissen, Die Fahrt ins Blaue, Artemis & Winkler Verlag, Düsseldorf, 2006, ISBN-13:978-3-538-07001-1

- Christina Althen: Alfred Döblin, Leben und Werk in Erzählungen und Selbstzeugnissen, Arzt und Dichter, Artemis & Winkler Verlag, Düsseldorf, 2006, ISBN-13:978-3-538-07001-1

- Christina Althen: Alfred Döblin, Leben und Werk in Erzählungen und Selbstzeugnissen, Arzt und Dichter, Artemis & Winkler Verlag, Düsseldorf, 2006, ISBN-13:978-3-538-07001-1

- Die Freigabe der Vernichtung lebensunwerten Lebens. Ihr Maß und ihre Form (1920).BWV Berliner Wissenschaftsverlag, Berlin 2006, ISBN 3-8305-1169-8.

ANNETTE TUFFS, MD, studied medicine at the universities of Giessen, Würzburg, Cambridge (UK), and Bonn. She wrote her doctoral thesis (Bonn University) on the effects of ultraviolet light on eye lenses and has worked as a science journalist and communication director. She lives in Heidelberg and Berlin, Germany.

Winter 2018 | Sections | Psychiatry & Psychology

Leave a Reply